The Unfurling Scroll of Wellness: Lemongrass and the Ancient Battle Against Inflammation

In the intricate tapestry of human health, few threads are as pervasive, yet as misunderstood, as inflammation. Once hailed as the body’s vigilant sentinel, a fiery response to injury and invasion, it has, in the relentless march of modern life, morphed into a silent saboteur. Chronic, low-grade inflammation now underpins a dizzying array of modern maladies, from the stiffness of arthritis to the insidious progression of cardiovascular disease, from the fog of neurodegenerative disorders to the relentless proliferation of cancer cells. It is a foe that demands not just suppression, but understanding and nuanced intervention.

Against this complex backdrop, a humble, aromatic grass, long cherished in the sun-drenched kitchens and healing traditions of the East, emerges as a surprising champion: Cymbopogon citratus, commonly known as lemongrass. Its story is not one of dramatic, synthetic intervention, but of gentle, yet profound, biological orchestration – a testament to the enduring wisdom of nature and the meticulous unveiling of its secrets by modern science. For the knowledgeable audience, aware of the molecular dance that dictates health and disease, the narrative of lemongrass is a compelling one, a tale of potent anti-inflammatory power woven into its very essence, waiting to be fully appreciated and harnessed.

The Double-Edged Sword: Understanding Inflammation’s Nuances

To truly appreciate lemongrass’s contribution, we must first delve deeper into the nature of inflammation itself. It is a fundamental physiological process, an immediate and localized protective response initiated by the body’s immune system to eliminate harmful stimuli – pathogens, damaged cells, irritants – and initiate the healing process. This is acute inflammation, characterized by the classic signs of redness (rubor), heat (calor), swelling (tumor), pain (dolor), and loss of function (functio laesa). It’s a symphony of cellular and molecular events, orchestrated by a complex interplay of immune cells, cytokines, chemokines, and eicosanoids, all working in concert to restore homeostasis.

However, when this protective mechanism becomes dysregulated, prolonged, or inappropriately activated, it transforms into chronic inflammation. This insidious state, often asymptomatic for extended periods, is a major driver of pathology. Unlike acute inflammation, which is typically resolved within days, chronic inflammation can persist for months or years, leading to progressive tissue destruction and the development of numerous chronic diseases. The key players in this prolonged battle include macrophages, lymphocytes, and plasma cells, which infiltrate tissues, continually releasing pro-inflammatory mediators.

At the molecular heart of this process lies a complex web of signaling pathways. One of the most critical is the NF-κB (Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells) pathway. NF-κB is a protein complex that controls the transcription of DNA, cytokine production, and cell survival. In its inactive state, it resides in the cytoplasm, bound by inhibitory proteins. Upon activation by various stimuli (e.g., pathogens, stress, reactive oxygen species), it translocates to the nucleus, where it binds to specific DNA sequences, initiating the transcription of genes encoding pro-inflammatory cytokines (like TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6), chemokines, adhesion molecules, and enzymes like COX-2 and iNOS. Dysregulation of NF-κB is a hallmark of many inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, and its sustained activation is a primary driver of chronic inflammation.

Another crucial family of mediators are the eicosanoids, particularly prostaglandins and leukotrienes, derived from arachidonic acid. The enzymes Cyclooxygenase (COX), specifically COX-1 and COX-2, are central to prostaglandin synthesis. COX-1 is constitutively expressed and involved in maintaining physiological functions like gastric protection and renal blood flow. COX-2, on the other hand, is largely inducible, expressed during inflammation, and a key target for anti-inflammatory drugs. The selective inhibition of COX-2, while sparing COX-1, is a common pharmacological strategy to reduce inflammation while minimizing side effects like gastrointestinal irritation.

This molecular understanding provides the essential lens through which we can now appreciate the profound impact of natural compounds. The challenge lies in finding agents that can modulate these pathways effectively, safely, and without the myriad side effects often associated with synthetic pharmaceuticals.

Lemongrass: From Ancient Brew to Modern Elixir

The story of lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus) begins in the verdant landscapes of Southeast Asia, particularly India and Sri Lanka, where it has been cultivated for millennia. Its vibrant, citrusy aroma and flavor, reminiscent of lemon with earthy undertones, quickly earned it a place in regional cuisines, particularly Thai, Vietnamese, and Indian, where it forms the aromatic backbone of curries, soups, and teas.

But its role transcended the culinary. Traditional Ayurvedic and Unani medicine systems revered lemongrass for its medicinal properties. Practitioners employed it as a febrifuge (fever reducer), a digestive aid, a diuretic, and a diaphoretic (to induce sweating). It was used to alleviate pain, treat skin infections, and calm nervous disorders. The wisdom of these ancient practices, often passed down through generations, implicitly recognized its systemic benefits, even without the language of cytokines and gene transcription.

The "story" here is one of slow, deliberate recognition. For centuries, its healing potential remained largely within the confines of traditional knowledge. It was only in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, driven by a global resurgence of interest in natural products and advancements in phytochemistry, that scientists began to meticulously peel back the layers of anecdotal evidence, seeking to identify the bioactive compounds responsible for these profound effects. What they discovered was a veritable pharmacopeia within this unassuming grass, particularly a powerful arsenal against inflammation.

The Phytochemical Powerhouse: Unveiling Lemongrass’s Anti-Inflammatory Arsenal

The true magic of lemongrass lies in its complex chemical composition, a symphony of compounds working in concert. While many constituents contribute to its overall therapeutic profile, a select few stand out as potent anti-inflammatory agents.

1. Citral: The Orchestrator of Anti-Inflammatory Action

The undisputed star of lemongrass’s chemical ensemble is citral, a mixture of two isomeric aldehydes, geranial (trans-citral) and neral (cis-citral). Comprising up to 65-85% of lemongrass essential oil, citral is not merely responsible for its distinctive lemony aroma; it is a profound modulator of inflammatory pathways.

- NF-κB Pathway Inhibition: Research has compellingly demonstrated citral’s ability to interfere with the NF-κB signaling pathway. It achieves this by inhibiting the degradation of IκB-α, the inhibitory protein that sequesters NF-κB in the cytoplasm. By preventing IκB-α degradation, citral effectively blocks NF-κB’s translocation to the nucleus, thus preventing the transcription of numerous pro-inflammatory genes. This direct hit on a central regulator of inflammation is a cornerstone of its efficacy.

- COX-2 Inhibition: Citral has also been shown to significantly downregulate the expression and activity of COX-2. By inhibiting this inducible enzyme, citral curtails the production of pro-inflammatory prostaglandins, mirroring the action of many conventional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) but potentially with a more favorable safety profile due to its pleiotropic actions and the synergistic effects of other compounds.

- Cytokine Modulation: Beyond NF-κB and COX-2, citral actively modulates the production of key pro-inflammatory cytokines. Studies have shown its capacity to reduce the levels of TNF-α (Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha), a master regulator of inflammation and a target for biological therapies in autoimmune diseases, as well as IL-1β (Interleukin-1 beta) and IL-6 (Interleukin-6), all crucial drivers of inflammatory cascades and tissue damage.

- Nitric Oxide Synthase (iNOS) Inhibition: Chronic inflammation often involves the excessive production of nitric oxide (NO) by inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), which can lead to oxidative stress and tissue damage. Citral has been found to suppress iNOS expression, thereby reducing NO production and mitigating inflammatory damage.

2. Geraniol: The Synergistic Partner

Another significant terpene in lemongrass is geraniol. While also contributing to the plant’s fragrance, geraniol itself possesses notable anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant properties. It has been shown to reduce inflammatory markers in various in vitro and in vivo models, often by modulating NF-κB and MAPK pathways, and by scavenging free radicals, thus complementing citral’s actions. Its presence highlights the concept of synergy, where multiple compounds work together to produce a greater effect than any single compound alone.

3. Myrcene: A Calming Influence

Myrcene, a monoterpene found in a variety of plants, is also present in lemongrass. It has been studied for its analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects, particularly in pain models. Its mechanism often involves interactions with opioid receptors and inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis, further adding to lemongrass’s pain-relieving and inflammation-reducing capabilities.

4. Flavonoids: Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Sentinels

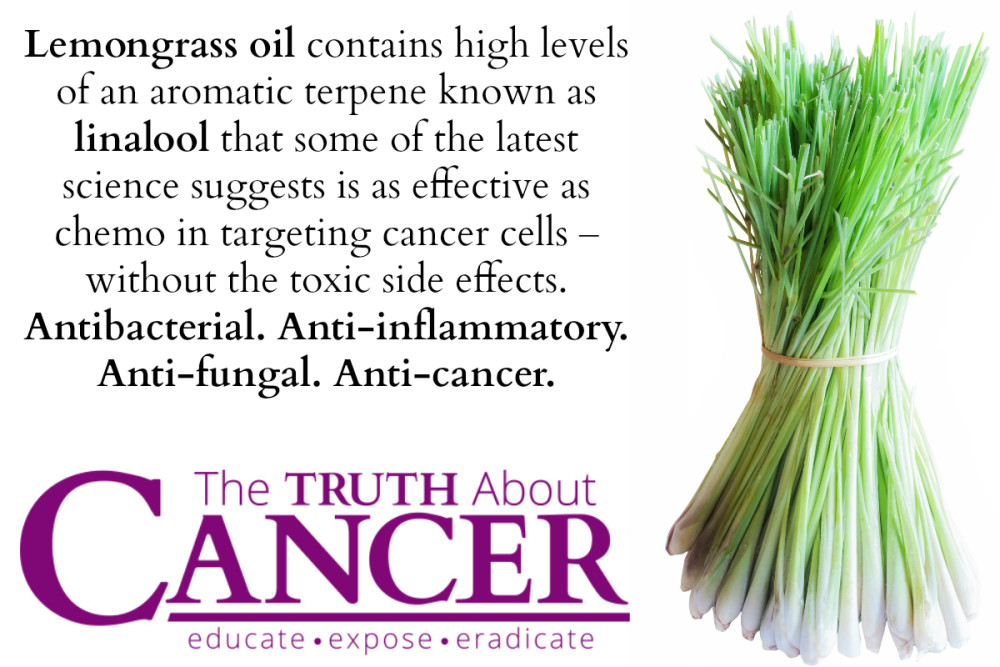

Lemongrass also contains a rich array of flavonoids, including luteolin, apigenin, quercetin, and kaempferol. These polyphenolic compounds are renowned for their potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities.

- Antioxidant Power: Flavonoids are excellent free radical scavengers, neutralizing reactive oxygen species (ROS) that contribute to oxidative stress, a known precursor and perpetuator of inflammation. By mitigating oxidative stress, they indirectly dampen inflammatory pathways.

- Direct Anti-Inflammatory Actions: Beyond their antioxidant role, many flavonoids directly interfere with inflammatory signaling. For instance, luteolin and apigenin have been shown to inhibit NF-κB activation, suppress pro-inflammatory cytokine production, and modulate enzyme activities involved in inflammation. Quercetin, another powerful flavonoid, is known to stabilize mast cells, reducing histamine release, and inhibit various inflammatory enzymes.

5. Phenolic Acids and Other Constituents:

While in lesser quantities than citral, other phenolic acids, such as caffeic acid and chlorogenic acid, also contribute to the plant’s antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. The holistic effect of lemongrass is thus a complex interplay, a botanical ensemble where each component contributes to the overall therapeutic symphony.

Mechanisms Unpacked: How Lemongrass Re-Calibrates the Inflammatory Response

For the knowledgeable reader, a deeper dive into the specific mechanisms reveals the sophistication of lemongrass’s action. It’s not a brute-force attack but a targeted modulation, a re-calibration of the body’s own regulatory systems.

1. Downregulation of Pro-inflammatory Gene Expression:

The most significant mechanism is the direct or indirect inhibition of the NF-κB pathway. By preventing NF-κB’s activation and nuclear translocation, lemongrass compounds effectively silence the genetic instructions for producing a cascade of inflammatory mediators. This includes:

- Cytokines: TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6. These are the "generals" of the inflammatory response, signaling other cells and amplifying the cascade. Reducing their production can significantly dampen systemic inflammation.

- Chemokines: Proteins that recruit inflammatory cells (like neutrophils and macrophages) to the site of injury.

- Adhesion Molecules: Proteins on cell surfaces that allow inflammatory cells to stick to blood vessel walls and migrate into tissues.

- Enzymes: COX-2 and iNOS, which generate prostaglandins and nitric oxide, respectively, both potent inflammatory mediators.

2. Selective COX-2 Inhibition:

While synthetic NSAIDs like celecoxib specifically target COX-2 to reduce inflammation and pain, they are not without side effects, particularly cardiovascular risks with long-term use. Lemongrass, through compounds like citral, demonstrates a natural capacity to inhibit COX-2. This is critical because COX-2 is largely responsible for the production of pro-inflammatory prostaglandins at sites of inflammation, while COX-1 is more involved in homeostatic functions. The plant’s ability to modulate COX-2 expression and activity offers a gentler, potentially safer approach to managing prostaglandin-mediated inflammation.

3. Antioxidant Defense:

Chronic inflammation is intrinsically linked to oxidative stress. Inflammatory cells produce large amounts of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), which can damage cellular components (DNA, proteins, lipids) and perpetuate the inflammatory cycle. Lemongrass, rich in flavonoids and other phenolics, acts as a potent antioxidant. It directly scavenges free radicals, reduces lipid peroxidation, and can even upregulate endogenous antioxidant enzymes like superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase. By reducing oxidative burden, lemongrass breaks a crucial link in the inflammation-damage feedback loop.

4. Modulation of Cell Signaling Pathways (MAPKs):

Beyond NF-κB, other signaling pathways like the Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) pathways (e.g., ERK, JNK, p38) are also involved in inflammatory responses. Some studies suggest that lemongrass compounds can modulate these pathways, further fine-tuning the cellular response to inflammatory stimuli.

5. Apoptosis and Cell Cycle Arrest (in certain contexts):

While primarily an anti-inflammatory agent, some research, particularly in cancer models, indicates that citral and other lemongrass compounds can induce apoptosis (programmed cell death) in abnormal cells and arrest cell cycle progression. While this isn’t a direct anti-inflammatory mechanism, it highlights the pleiotropic nature of these compounds and their potential in conditions where uncontrolled cell proliferation is linked to chronic inflammation (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease and its link to colorectal cancer).

Traditional Wisdom Meets Modern Validation: The Clinical Journey

The journey of lemongrass from traditional folk remedy to scientifically validated anti-inflammatory agent is a compelling narrative of scientific inquiry.

In Vitro Studies (Cell Culture):

The initial validation often comes from in vitro studies, where lemongrass extracts and isolated compounds are tested on various cell lines (e.g., macrophages, endothelial cells) stimulated with pro-inflammatory agents (like LPS – lipopolysaccharide). These studies consistently show:

- Reduced production of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and NO.

- Inhibition of NF-κB activation and COX-2 expression.

- Protection against oxidative stress in inflammatory conditions.

These foundational studies provide the molecular blueprint for its anti-inflammatory action.

In Vivo Studies (Animal Models):

Moving from the petri dish to living organisms, in vivo studies using animal models of inflammation have further solidified lemongrass’s therapeutic potential:

- Arthritis Models: In models of rheumatoid arthritis (e.g., collagen-induced arthritis) or osteoarthritis, lemongrass extracts have been shown to reduce joint swelling, decrease inflammatory markers (like C-reactive protein, ESR), and protect cartilage from degradation.

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) Models: In models of colitis (e.g., DSS-induced colitis), lemongrass administration has been shown to reduce colon inflammation, improve gut barrier function, and decrease the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the gut mucosa.

- Edema Models: In acute inflammation models, such as carrageenan-induced paw edema, lemongrass essential oil and extracts have demonstrated significant anti-edematous and analgesic effects, comparable to conventional NSAIDs in some cases.

- Pain Models: Its analgesic properties, often intertwined with its anti-inflammatory action, have been observed in various pain models, suggesting its utility in inflammatory pain conditions.

Human Studies (Emerging Evidence):

While extensive large-scale human clinical trials specifically focusing on lemongrass’s anti-inflammatory properties are still emerging, preliminary studies and anecdotal evidence from traditional use are promising.

- Topical Applications: Lemongrass essential oil, diluted and applied topically, has been traditionally used for muscular aches and pains, and some small studies support its efficacy in reducing pain and inflammation associated with conditions like carpal tunnel syndrome or tension headaches. Its ability to penetrate the skin and deliver localized anti-inflammatory compounds is a significant advantage.

- Oral Consumption: While much of the research on oral intake focuses on its antioxidant, antimicrobial, or anti-cancer properties, the systemic absorption of its active compounds, particularly citral, suggests a broader anti-inflammatory impact. Regular consumption as a tea or culinary ingredient, therefore, likely contributes to a reduction in systemic low-grade inflammation.

The "story" here is the growing convergence of traditional wisdom and rigorous scientific validation, moving lemongrass from the realm of belief to evidence-based understanding.

Broadening Horizons: Therapeutic Applications and Potential

Given its multi-faceted anti-inflammatory mechanisms, lemongrass holds promise across a spectrum of health conditions where inflammation plays a pivotal role:

-

Rheumatic Conditions: For conditions like osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis, where chronic inflammation damages joints, lemongrass could offer a complementary therapy to alleviate pain, reduce swelling, and potentially slow disease progression by modulating inflammatory pathways and providing antioxidant support.

-

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): The targeted reduction of gut inflammation, modulation of cytokine profiles, and protection against oxidative stress make lemongrass a compelling candidate for adjunct therapy in conditions like Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Its ability to improve gut barrier function is particularly relevant in IBD pathogenesis.

-

Metabolic Syndrome and Type 2 Diabetes: Chronic low-grade inflammation is a hallmark of metabolic syndrome, contributing to insulin resistance, obesity, and cardiovascular risk. By dampening this systemic inflammation, lemongrass could play a supportive role in improving metabolic health.

-

Neuroinflammation: Inflammation in the brain and nervous system (neuroinflammation) is increasingly recognized as a key factor in neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. While research is nascent, the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties of lemongrass compounds, particularly their ability to cross the blood-brain barrier (for some compounds), suggest a potential role in mitigating neuroinflammatory processes.

-

Skin Conditions: Topically, its anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial properties could be beneficial for inflammatory skin conditions like acne, eczema, and dermatitis, helping to reduce redness, swelling, and irritation.

-

Respiratory Conditions: For inflammatory conditions of the respiratory tract, such as asthma or bronchitis, the inhalation of lemongrass essential oil (via diffusion) or consumption of its tea could help soothe inflamed airways and reduce inflammatory responses, though more research is needed in this specific application.

Integrating Lemongrass into a Wellness Routine: Practical Considerations

For the knowledgeable audience looking to leverage this botanical powerhouse, practical application is key.

- Culinary Use: The easiest and safest way to incorporate lemongrass is through cooking. Use fresh stalks in teas, soups, curries, marinades, and stir-fries. This provides a gentle, consistent intake of its beneficial compounds.

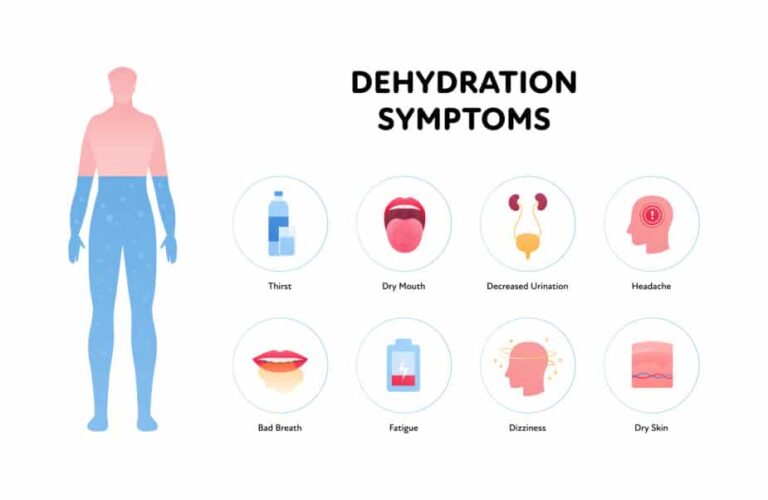

- Lemongrass Tea: A simple infusion of fresh or dried lemongrass leaves is a traditional and effective way to consume its anti-inflammatory compounds. Steep 1-2 stalks (or 1-2 teaspoons dried) in hot water for 5-10 minutes.

- Essential Oil (Topical): Lemongrass essential oil is highly concentrated and should never be applied undiluted to the skin. Dilute it with a carrier oil (e.g., jojoba, almond, coconut oil) at a concentration of 1-3% for topical application to sore muscles, joints, or areas of localized inflammation. Perform a patch test first.

- Aromatherapy: Diffusing lemongrass essential oil can create a calming atmosphere, and some research suggests that inhaled terpenes can have systemic effects, though its direct anti-inflammatory benefits via inhalation require more targeted study.

- Supplements/Extracts: Standardized lemongrass extracts or supplements are available, offering a more concentrated dose of active compounds. Always choose reputable brands and consult with a healthcare professional before starting any new supplement, especially if you have underlying health conditions or are taking medications.

Safety and Considerations: A Prudent Approach

While generally recognized as safe (GRAS) for culinary use, a knowledgeable approach includes understanding potential precautions:

- Allergies: Some individuals may be sensitive or allergic to lemongrass, especially its essential oil. Symptoms can include skin irritation, rash, or respiratory issues. Always perform a patch test for topical use.

- Pregnancy and Breastfeeding: Due to insufficient research, pregnant and breastfeeding women should exercise caution and consult their healthcare provider before using lemongrass medicinally or in essential oil form.

- Drug Interactions: Highly concentrated lemongrass essential oil or extracts might theoretically interact with certain medications, such as blood thinners (due to potential antiplatelet effects, though typically mild with culinary use) or medications metabolized by the liver. Always discuss with a doctor if you are on prescription drugs.

- Essential Oil Dilution: Emphasize again: lemongrass essential oil is potent. Always dilute it properly for topical use and never ingest it unless under the direct guidance of a qualified practitioner.

The Unfolding Future: Lemongrass on the Horizon

The story of lemongrass as an inflammation fighter is far from over; it is, in many ways, just beginning to unfold in the modern scientific narrative. The future holds immense potential:

- More Human Clinical Trials: The most critical next step is the conduct of rigorous, placebo-controlled human clinical trials to definitively establish optimal dosages, efficacy, and safety profiles for specific inflammatory conditions.

- Synergistic Formulations: Research into combining lemongrass with other anti-inflammatory botanicals could unlock even greater therapeutic potential through synergistic effects.

- Targeted Delivery Systems: Developing novel delivery methods, such as nano-encapsulation or liposomal formulations, could enhance the bioavailability and targeted delivery of lemongrass’s active compounds to inflammatory sites.

- Understanding Metabolites: Further research into the metabolic fate of lemongrass compounds in the human body – how they are absorbed, metabolized, and exert their effects – will provide deeper insights into their mechanisms of action.

- Preventive Role: Exploring its long-term potential as a dietary component for the prevention of chronic inflammatory diseases, rather than just a treatment, is a promising avenue.

Conclusion: A Whisper of Ancient Wisdom, A Roar of Modern Science

The journey of lemongrass, from a fragrant staple in ancient kitchens to a scrutinized subject in modern laboratories, tells a compelling story. It is a narrative that bridges the gap between traditional wisdom and contemporary scientific understanding, revealing a humble grass as a formidable opponent against the pervasive threat of inflammation. Through its intricate array of bioactive compounds, particularly the multifaceted citral, lemongrass orchestrates a gentle yet powerful modulation of key inflammatory pathways – silencing pro-inflammatory genes, inhibiting crucial enzymes, and neutralizing oxidative stress.

For the knowledgeable, who understand the delicate balance of molecular biology that dictates health, lemongrass represents more than just a culinary herb; it is a profound botanical ally. Its story is a testament to the enduring power of nature, offering a path towards re-calibrating the body’s inflammatory response, not through aggressive suppression, but through intelligent, holistic intervention. As science continues to unfurl the scroll of its secrets, lemongrass stands poised to claim its rightful place as a potent, natural inflammation fighter, inviting us to embrace its ancient wisdom for modern well-being.