The Science of Sour: Kimchi’s Role in a Balanced Gut

The crimson embrace of kimchi, a culinary icon steeped in Korean heritage, offers far more than a tantalizing burst of piquant, sour, and umami flavors. It is a living testament to an ancient alchemy, a symphony of microorganisms transforming humble vegetables into a dynamic powerhouse of health. For the knowledgeable palate and the scientifically curious mind, kimchi presents a profound narrative – a story of microscopic architects meticulously building a foundation for human well-being, primarily through its transformative influence on the enigmatic world within our gut. This article delves into the intricate science behind kimchi’s sour magic, unraveling its multifaceted role in fostering a balanced and thriving gut microbiome, and by extension, a healthier self.

The Ancient Art, The Modern Science: A Legacy of Fermentation

Humanity’s relationship with fermentation is as old as civilization itself, born from necessity – a clever strategy for food preservation before the advent of refrigeration. Across cultures, this microbial artistry yielded everything from bread and cheese to wine and beer. In Korea, this ancient wisdom culminated in kimchi, a staple that has graced tables for millennia, evolving from simple salted vegetables to the complex, spicy, and deeply flavorful concoction we recognize today. Its cultural significance is so profound that "kimjang," the traditional communal act of making and sharing kimchi, is recognized by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

Yet, beyond the cultural tapestry and the sheer joy of its taste, modern science has begun to peel back the layers of kimchi’s enduring legacy, revealing a sophisticated biological machinery at play. The true magic, it turns out, resides not just in the ingredients, but in the invisible realm of microorganisms that orchestrate its transformation. These microscopic entities are the unsung heroes, turning simple cabbage and spices into a probiotic elixir, a functional food that stands as a beacon for gut health.

The Alchemy of Fermentation: What Makes Kimchi Sour and Beneficial?

At its core, kimchi is a product of lactic acid fermentation, a metabolic process carried out primarily by a diverse group of bacteria known as Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB). While various strains contribute, Lactobacillus species are often the most dominant, alongside Leuconostoc, Weissella, and Pediococcus. These beneficial microbes, naturally present on the raw vegetables (chiefly napa cabbage, radish, and scallions), begin their work once the vegetables are salted and then submerged in a brine infused with a medley of ingredients: garlic, ginger, gochugaru (Korean chili powder), fish sauce, and often other fruits and vegetables.

The salting process serves multiple critical functions. Firstly, it draws out water from the vegetables, creating a more concentrated environment for fermentation. Secondly, it inhibits the growth of undesirable spoilage bacteria and pathogens, creating a selective environment where salt-tolerant LAB can thrive. As these LAB consume the carbohydrates (sugars) present in the vegetables, they metabolize them into a range of organic acids, most notably lactic acid, but also acetic acid and propionic acid.

This production of acids is the "science of sour." As the pH of the kimchi mixture drops, it achieves several vital outcomes:

- Preservation: The acidic environment acts as a natural preservative, inhibiting the growth of most spoilage microorganisms and pathogenic bacteria, allowing kimchi to be stored for extended periods.

- Flavor Development: The acids contribute significantly to kimchi’s characteristic tangy, sour taste. Alongside other enzymatic reactions, they also unlock and create a complex array of volatile compounds that contribute to its unique aroma and umami depth.

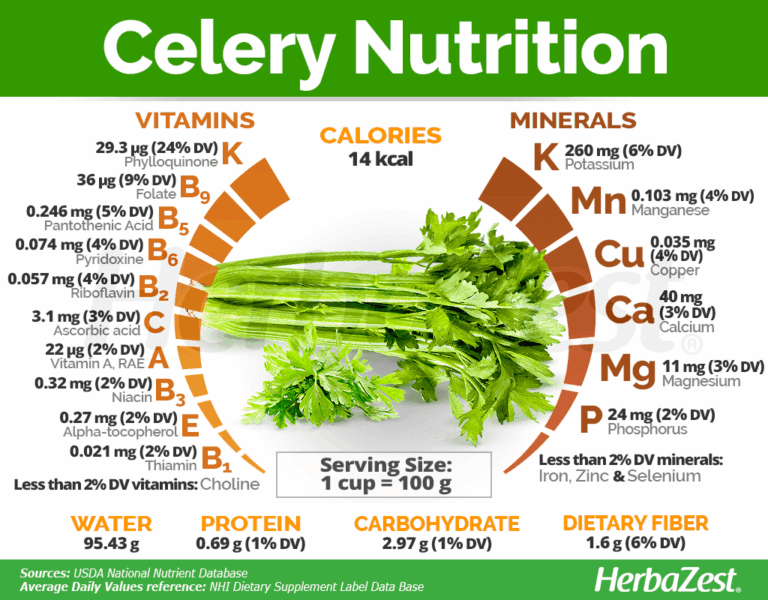

- Nutrient Enhancement: Fermentation can increase the bioavailability of certain nutrients by breaking down anti-nutritional factors and synthesizing new compounds, including B vitamins and vitamin K.

- Probiotic Powerhouse: Most importantly for our discussion, the fermentation process cultivates a rich and diverse community of live, beneficial bacteria – the probiotics that are crucial for gut health.

The precise microbial community in kimchi is dynamic, shifting over the course of fermentation, influenced by temperature, salt concentration, and the specific ingredients used. A freshly made kimchi will have a different microbial profile and flavor compared to one that has been aged for several weeks or months. This natural variability underscores the complexity and richness of this living food.

Inside the Gut Ecosystem: A Microscopic Metropolis

To truly appreciate kimchi’s impact, we must first understand its primary target: the human gut microbiome. Far from being a mere digestive tube, the gut is a bustling metropolis, home to trillions of microorganisms – bacteria, viruses, fungi, and archaea – collectively weighing as much as a human brain. This intricate ecosystem, dominated by bacteria, forms a complex web of interactions with our physiology, influencing everything from nutrient absorption and immune function to mood and cognitive health.

A "balanced gut" or "eubiosis" signifies a diverse and stable community of beneficial microbes, where pathogenic species are kept in check. Conversely, "dysbiosis" refers to an imbalance, a disruption in this microbial harmony, often characterized by a reduction in beneficial species and an overgrowth of potentially harmful ones. Dysbiosis has been implicated in a wide array of health issues, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), obesity, type 2 diabetes, allergies, autoimmune conditions, and even neurodegenerative disorders.

Kimchi, as a potent source of live probiotics, plays a pivotal role in promoting eubiosis. When consumed, these beneficial bacteria embark on a journey through the digestive tract, some transiently passing through, while others may temporarily colonize the gut. Their presence contributes to gut balance in several ways:

- Competitive Exclusion: Probiotic bacteria compete with harmful pathogens for nutrients and adhesion sites on the intestinal lining, effectively crowding out undesirable microbes.

- Production of Antimicrobial Compounds: LAB can produce bacteriocins, which are proteinaceous toxins that inhibit the growth of specific harmful bacteria, further safeguarding the gut environment.

- Modulation of pH: While the acids in kimchi contribute to its preservation, some probiotic strains can continue to produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) within the gut. SCFAs, such as acetate, propionate, and especially butyrate, are critical for gut health. Butyrate, for instance, is the primary energy source for colonocytes (cells lining the colon) and plays a crucial role in maintaining gut barrier integrity.

- Prebiotic Effect: Beyond the live cultures, kimchi’s fibrous vegetable base acts as a prebiotic. Dietary fiber, which human enzymes cannot digest, travels largely intact to the large intestine, where it serves as fermentable fuel for the native beneficial bacteria already residing there. This synergistic effect – introducing new beneficial bacteria (probiotics) and nourishing existing ones (prebiotics) – amplifies kimchi’s impact.

Beyond the Belly: Systemic Health Benefits

The ripple effect of a balanced gut microbiome extends far beyond the digestive tract, influencing virtually every system in the body. Kimchi’s contribution to gut health thus translates into a cascade of systemic benefits:

-

Immune System Fortification: Approximately 70-80% of the body’s immune cells reside in the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT). A healthy gut microbiome is a key orchestrator of immune responses. Probiotics in kimchi can modulate cytokine production (signaling molecules that regulate immunity), enhance the activity of immune cells, and strengthen the gut barrier. A robust gut barrier prevents undigested food particles, toxins, and pathogens from "leaking" into the bloodstream, a phenomenon known as "leaky gut," which can trigger systemic inflammation and autoimmune responses. Regular consumption of kimchi has been associated with enhanced immune responses and a reduced incidence of infections.

-

Metabolic Health and Weight Management: The gut microbiome plays a significant role in metabolic regulation. SCFAs, particularly butyrate, have been shown to improve insulin sensitivity, reduce inflammation, and influence energy expenditure. Some studies suggest that the consumption of fermented foods like kimchi can positively impact lipid profiles, helping to lower cholesterol levels, and may play a role in weight management by influencing satiety hormones and fat storage. The capsaicin in gochugaru also has thermogenic properties, potentially boosting metabolism.

-

The Brain-Gut Axis and Mental Well-being: The "gut-brain axis" is a bidirectional communication network linking the central nervous system with the enteric nervous system of the gut. Microbes in the gut produce a wide array of neuroactive compounds, including neurotransmitters like serotonin (a significant portion of which is produced in the gut), GABA, and dopamine, as well as SCFAs and other metabolites that can cross the blood-brain barrier. Through the vagus nerve, endocrine signals, and immune pathways, the gut microbiome profoundly influences mood, cognitive function, and behavior. Emerging research suggests that a diverse gut microbiome, fostered by probiotic-rich foods like kimchi, may alleviate symptoms of anxiety and depression, improve stress resilience, and potentially even offer neuroprotective benefits.

-

Anti-Cancer Potential: Kimchi’s ingredients and fermentation products contribute to its potential anti-cancer properties. The cruciferous vegetables (cabbage, radish) contain glucosinolates, which are broken down into bioactive compounds like sulforaphane and indole-3-carbinol (I3C) during fermentation and digestion. These compounds have demonstrated potent anti-cancer effects, including inhibiting tumor growth, inducing apoptosis (programmed cell death) in cancer cells, and detoxifying carcinogens. Furthermore, the beneficial bacteria themselves can produce compounds that may suppress the growth of certain cancer cells and modulate immune surveillance against cancerous transformations.

-

Skin Health (The Gut-Skin Axis): The interconnectedness of the body means that gut health often manifests on the skin. Dysbiosis and systemic inflammation can exacerbate skin conditions like acne, eczema, and psoriasis. By reducing inflammation, strengthening the immune system, and promoting a balanced gut, kimchi indirectly contributes to clearer, healthier skin. The antioxidants present in kimchi, such as those from garlic and gochugaru, also protect skin cells from oxidative damage.

The Nuances and The Future: Navigating Kimchi’s Potential

While the evidence for kimchi’s health benefits is compelling, it’s important to acknowledge the nuances. Not all kimchi is created equal.

- Live Cultures are Key: For probiotic benefits, kimchi must be unpasteurized. Pasteurization, a heat treatment designed to extend shelf life, kills the beneficial bacteria. Always check labels to ensure you’re consuming "live" or "raw" kimchi.

- Variability: Homemade kimchi, with its often diverse and robust microbial communities, may offer different benefits than mass-produced versions. The specific ingredients, fermentation time, and storage conditions all influence the final microbial profile.

- Sodium Content: Kimchi can be high in sodium due to the brining process. While a moderate intake is generally fine for most, individuals sensitive to sodium or with hypertension should consume it in moderation or seek out lower-sodium varieties.

- Individual Response: The human gut microbiome is highly individualized. While kimchi is broadly beneficial, the specific impact can vary from person to person depending on their existing microbial composition, genetics, and diet.

The science of sour is a continuously evolving field. Future research will undoubtedly delve deeper into the specific strains of bacteria in kimchi and their precise mechanisms of action. We can anticipate more studies exploring personalized nutrition approaches, where specific fermented foods are recommended based on an individual’s unique microbiome profile. The burgeoning field of epigenetics is also likely to shed light on how microbial metabolites from kimchi can influence gene expression, offering another layer of understanding regarding its long-term health impacts.

Conclusion: A Living Legacy for a Balanced Life

Kimchi is more than just a fermented vegetable; it is a living legacy, a testament to the profound connection between food, culture, and health. Its vibrant flavors are a direct result of the unseen labor of trillions of microorganisms, working in concert to create a food that not only delights the senses but also profoundly nourishes our inner ecosystem.

For the knowledgeable audience, the narrative of kimchi is a fascinating intersection of microbiology, immunology, neuroscience, and culinary art. It underscores the immense power of traditional foods, reimagined through the lens of modern science, to act as potent tools for health optimization. By embracing the science of sour, by regularly incorporating this ancient, complex, and deeply beneficial food into our diets, we are not merely enjoying a culinary delight; we are actively cultivating a balanced gut, bolstering our immune defenses, supporting our mental well-being, and ultimately, investing in a healthier, more vibrant future. The humble jar of kimchi, bubbling with life, offers a profound reminder that sometimes, the most extraordinary health benefits arise from the smallest, most overlooked corners of our world.