Raw vs. Cooked: Maximizing the Health Benefits of Kale in Your Diet

For years, I approached kale with a singular conviction. Like many health enthusiasts, I was a fervent devotee of the raw camp. The crisp, verdant leaves, massaged with lemon and olive oil, or blended into vibrant green smoothies, represented the pinnacle of nutrient integrity. The logic seemed irrefutable: heat, the destroyer of enzymes and fragile vitamins, surely diminished the very essence of this leafy titan. My refrigerator was a shrine to uncooked cruciferous power, and my dietary choices, a testament to the gospel of the living food.

But as I delved deeper into the intricate world of nutritional science, my rigid stance began to soften. The simplicity of "raw is always best" gave way to a fascinating complexity, a dance between preservation and transformation, liberation and degradation. The journey to truly maximize kale’s health benefits, I discovered, was not a binary choice between raw and cooked, but a sophisticated ballet of preparation methods, each unlocking a different facet of its profound nutritional potential. This article is the story of that evolving understanding, a guide for the discerning palate and the inquisitive mind, seeking to harness every ounce of goodness kale has to offer.

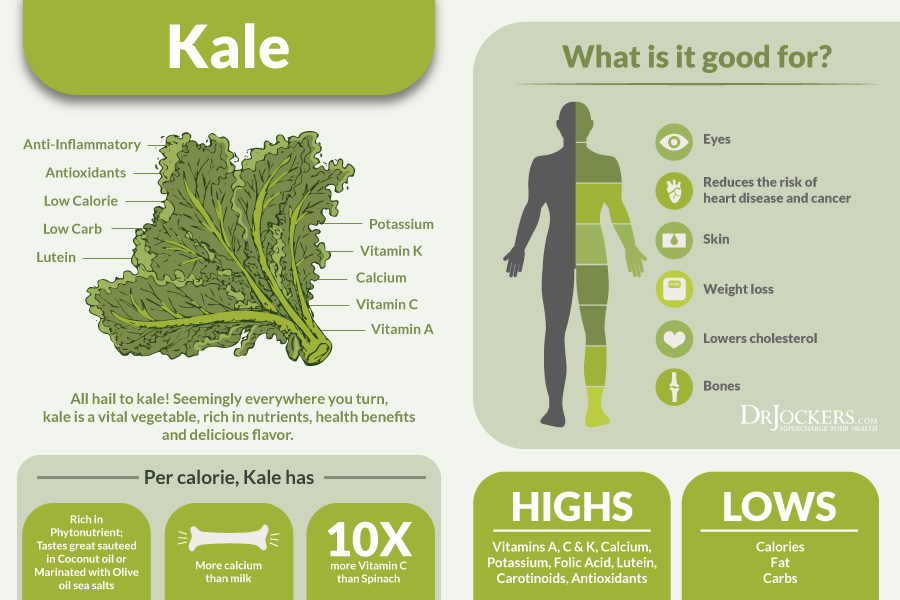

The Unveiling of a Superfood: Kale’s Nutritional Pedigree

Before we dissect the impact of heat, let’s first appreciate the raw material itself. Kale (Brassica oleracea var. sabellica) is not merely a vegetable; it’s a nutritional powerhouse, a verdant marvel lauded for its dense concentration of vitamins, minerals, fiber, and an astonishing array of bioactive compounds. It’s this multifaceted profile that has rightly earned it its superfood status.

At its core, kale is an exceptional source of Vitamin K, primarily in the form of phylloquinone (K1), crucial for blood clotting and bone health. A single cup of raw kale can provide over 100% of the daily recommended intake. It’s also brimming with Vitamin A (as beta-carotene, a potent antioxidant precursor to Vitamin A), essential for vision, immune function, and skin health. Vitamin C, a renowned immune booster and collagen synthesis aid, is present in significant quantities, rivaling citrus fruits.

Beyond these marquee vitamins, kale offers a rich tapestry of essential minerals: manganese, vital for bone development and metabolism; copper, involved in energy production and iron metabolism; potassium, critical for blood pressure regulation; and calcium, fundamental for bone and teeth health. Its substantial fiber content supports digestive regularity, satiety, and helps regulate blood sugar levels.

However, the true magic of kale, especially for the knowledgeable audience, lies in its phytonutrient profile. These plant-based compounds, while not traditionally classified as "essential" nutrients, exert profound health-promoting effects. Kale is particularly rich in:

- Glucosinolates: These sulfur-containing compounds are the precursors to isothiocyanates (ITCs), which are among the most studied anti-cancer compounds found in cruciferous vegetables. When kale’s cell walls are damaged (e.g., through chewing or chopping), an enzyme called myrosinase converts glucosinolates into various ITCs, such as sulforaphane, indole-3-carbinol (I3C), and phenethyl isothiocyanate (PEITC). These ITCs are potent detoxifiers, supporting the body’s phase I and phase II detoxification pathways, and have demonstrated anti-inflammatory and anti-proliferative properties.

- Flavonoids: Quercetin and kaempferol are two prominent flavonoids in kale, acting as powerful antioxidants and anti-inflammatory agents. They help neutralize free radicals, reduce oxidative stress, and may protect against chronic diseases like heart disease and certain cancers.

- Carotenoids: Beyond beta-carotene, kale is an excellent source of lutein and zeaxanthin. These carotenoids are vital for eye health, accumulating in the retina and protecting against age-related macular degeneration and cataracts.

This intricate symphony of nutrients and phytonutrients makes kale an indispensable component of a health-conscious diet. But the question remains: how do we best conduct this symphony – with the raw, vibrant energy of fresh greens, or the transformative power of heat?

The Case for Raw Kale: Unlocking the Untouched Potential

The argument for consuming kale raw rests primarily on the preservation of certain heat-sensitive compounds and the activation of specific enzymatic processes.

-

Enzymatic Activity (Myrosinase): This is perhaps the most compelling reason to eat kale raw. As mentioned, the enzyme myrosinase is crucial for converting glucosinolates into beneficial ITCs. Myrosinase is highly heat-sensitive, typically denaturing at temperatures above 140°F (60°C). When kale is consumed raw, especially after being thoroughly chewed or finely chopped, myrosinase effectively initiates the conversion process, leading to the formation of sulforaphane and other ITCs in the mouth and stomach. This direct, enzymatic conversion is often considered superior to relying solely on gut bacteria for later conversion, as the latter can be less efficient and variable among individuals.

-

Vitamin C Preservation: Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) is notoriously fragile. It’s water-soluble and easily degraded by heat, light, and oxygen. Raw kale offers its full complement of Vitamin C, contributing significantly to antioxidant defense, immune function, and collagen synthesis. Cooking methods, especially boiling, can lead to substantial losses of this vital nutrient.

-

Certain B Vitamins: While not as abundant as in some other sources, kale does contain B vitamins, including folate (B9), which are also water-soluble and can be diminished by heat.

-

Live Enzymes (General): Proponents of raw food diets often emphasize the importance of "live enzymes" in food, believing they aid digestion and reduce the body’s enzymatic burden. While the scientific consensus on the direct contribution of plant enzymes to human digestion (beyond specific examples like myrosinase) is still evolving and often debated, the principle of preserving them holds appeal for many.

-

Texture and Experience: For many, the crisp, slightly bitter, and peppery notes of raw kale are simply more appealing. It offers a satisfying crunch in salads, a vibrant green hue in smoothies, and a unique freshness that cooked kale cannot replicate.

However, the raw approach is not without its considerations, particularly for our knowledgeable audience.

Raw Kale’s Considerations (Anti-Nutrients and Digestibility):

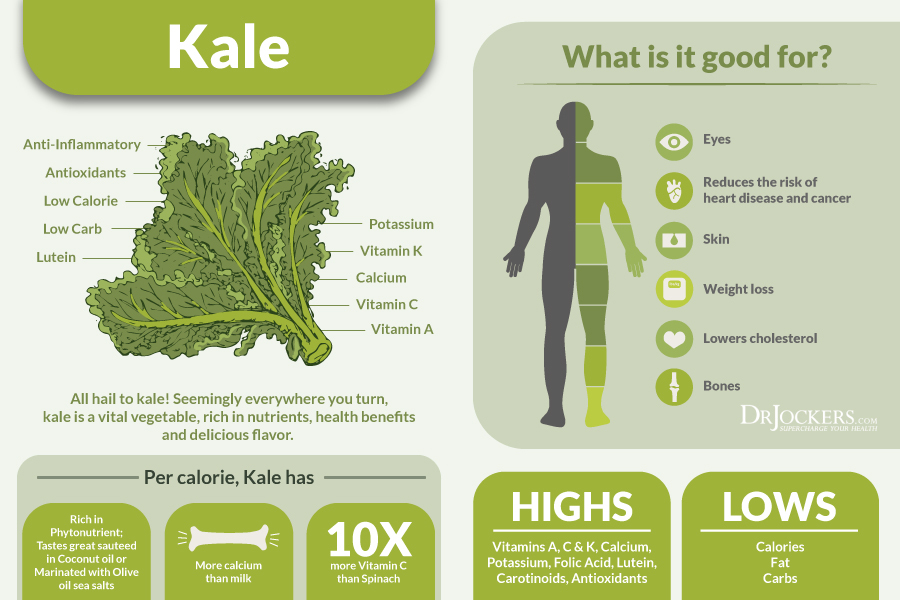

- Oxalates: Kale, like spinach and other dark leafy greens, contains oxalic acid (oxalates). These compounds can bind to minerals like calcium and magnesium, potentially reducing their absorption. For most healthy individuals consuming a balanced diet, this is rarely an issue. However, for individuals prone to kidney stones (which are often calcium oxalate stones) or those with compromised gut health, high oxalate intake might be a concern.

- Goitrogens: Kale contains goitrogenic compounds (specifically progoitrin), which can, in very high concentrations, interfere with thyroid function by inhibiting iodine uptake. This concern is often overblown; you would need to consume truly massive quantities of raw kale daily to experience a significant effect, especially if your iodine intake is adequate. Cooking significantly deactivates these compounds.

- Digestibility: The high fiber content and tough cell walls of raw kale can be challenging for some digestive systems, leading to bloating, gas, or discomfort. While massaging raw kale with oil and acid can help break down some of these fibers, it doesn’t entirely mitigate the issue for everyone.

The Case for Cooked Kale: Enhancing Bioavailability and Palatability

The transformative power of heat, far from being solely destructive, can unlock certain benefits in kale, making some nutrients more accessible and mitigating potential anti-nutrients.

-

Increased Bioavailability of Carotenoids: Cooking, especially with a bit of healthy fat (like olive oil), can significantly enhance the bioavailability of fat-soluble carotenoids like beta-carotene, lutein, and zeaxanthin. Heat helps to break down the tough cell walls of kale, releasing these compounds from their protein matrices and making them more readily absorbed in the digestive tract. Studies have shown that cooked kale can deliver more usable carotenoids than raw.

-

Reduced Oxalates and Goitrogens: This is a major advantage of cooking. Boiling or steaming kale can reduce its oxalate content by 50-80% as these water-soluble compounds leach into the cooking water. Similarly, cooking significantly deactivates the goitrogenic compounds, making kale a safer choice for those with thyroid concerns (though, again, the raw risk is generally low for most).

-

Improved Digestibility: Heat softens the fibrous structure of kale, making it easier to chew, digest, and assimilate nutrients. For individuals with sensitive digestive systems or those prone to bloating from raw vegetables, cooked kale can be a much more comfortable option.

-

Enhanced Flavor and Versatility: Cooking transforms kale’s sometimes bitter and tough texture into a tender, mellow, and more palatable vegetable. It opens up a vast culinary landscape, allowing kale to be incorporated into stir-fries, soups, stews, sautés, and casseroles, increasing its overall dietary inclusion.

Cooked Kale’s Considerations (Nutrient Loss):

- Myrosinase Inactivation: As highlighted, heat destroys myrosinase, the enzyme critical for converting glucosinolates into ITCs. This means that cooked kale, on its own, will produce fewer ITCs through direct enzymatic action.

- Vitamin C and B Vitamin Loss: Depending on the cooking method and duration, significant amounts of water-soluble vitamins like C and some B vitamins can be lost through heat degradation and leaching into cooking water.

- Other Phytonutrient Alterations: While some compounds become more bioavailable, others might be altered or reduced. The overall antioxidant capacity can sometimes be affected, though often in complex and nuanced ways depending on the specific compounds and cooking methods.

The Art of Preparation: Nuance in the Culinary Equation

The discussion isn’t just about raw vs. cooked; it’s about how you prepare it. Different cooking methods have varying impacts:

- Boiling: While effective at reducing oxalates and goitrogens, boiling leads to the greatest loss of water-soluble vitamins and minerals as they leach into the cooking water. If you must boil, keep the cooking time short and consider using the nutrient-rich water as a base for soups or broths.

- Steaming: This is often considered one of the best cooking methods for kale. It minimizes nutrient loss compared to boiling because the kale doesn’t come into direct contact with water, yet the heat is sufficient to soften fibers and reduce anti-nutrients. It preserves more Vitamin C and glucosinolates than boiling, though myrosinase is still largely inactivated.

- Sautéing/Stir-Frying: Using a small amount of healthy fat (like olive oil) in sautéing is excellent for increasing the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins (A, K) and carotenoids. The cooking time is usually short, which helps preserve some heat-sensitive nutrients.

- Blanching: A quick dip in boiling water followed by an ice bath. This can help tenderize kale for salads or other preparations, and reduces oxalates, but still incurs some nutrient loss.

- Baking/Roasting (Kale Chips): High heat for extended periods can lead to significant loss of some vitamins, but the resulting crispy texture can be a delicious way to consume kale.

Beyond the Heat: Pre-Preparation Matters

Even before heat is applied, certain techniques can enhance kale’s benefits:

- Chopping/Mincing: Mechanical damage to kale’s cell walls, whether by chewing or chopping, is essential for bringing glucosinolates and myrosinase into contact, initiating ITC formation. This is true for both raw and cooked preparations. Chop your kale well, even if you plan to cook it.

- "Resting" After Chopping: For maximizing ITCs, especially sulforaphane, chop your kale (or other cruciferous vegetables) and let it "rest" for 5-10 minutes before cooking. This allows myrosinase to work its magic before it’s denatured by heat.

- Adding Myrosinase-Rich Foods: If you’re cooking kale and thus inactivating its inherent myrosinase, you can strategically add other myrosinase-rich foods to your meal. A sprinkle of raw mustard seeds, daikon radish, horseradish, or even a small amount of raw broccoli sprouts after cooking your kale can provide the enzyme needed to convert the remaining glucosinolates into ITCs. This is a brilliant hack for getting the best of both worlds!

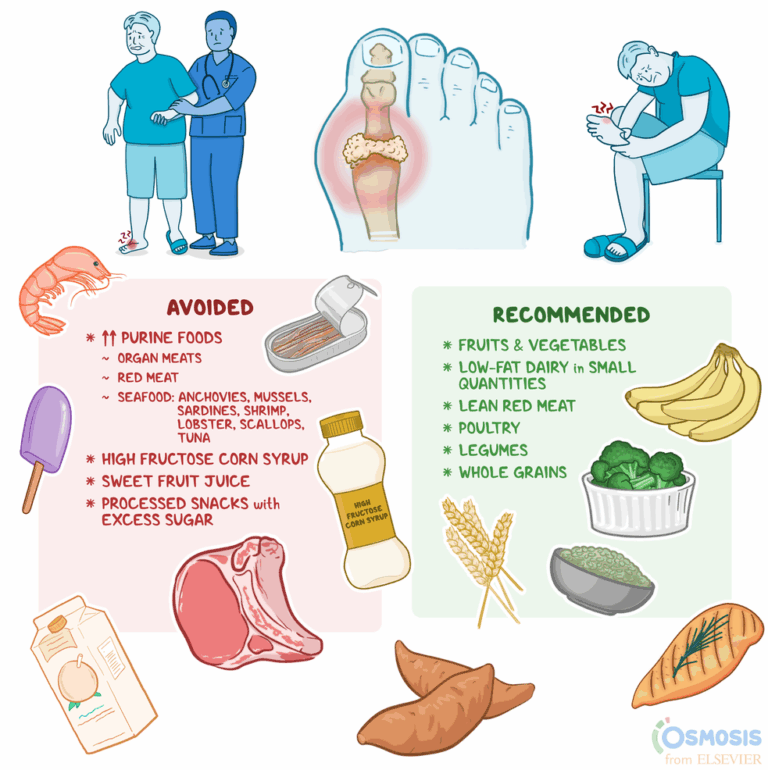

- Massaging Raw Kale: For raw kale salads, massaging the leaves with olive oil and a touch of acid (lemon juice or vinegar) not only tenderizes them and makes them more palatable but also helps break down cell walls, potentially enhancing nutrient release and aiding digestion.

The Synthesis: A Holistic Approach to Kale Consumption

My journey through the scientific literature and culinary experimentation led me to a profound realization: the question isn’t "raw or cooked," but "how can I intelligently incorporate both, leveraging the unique strengths of each?" The answer lies in diversity and thoughtful preparation.

Imagine kale as a multi-faceted gem, with each preparation method illuminating a different facet.

-

The Raw Powerhouse: Start your day with a green smoothie featuring raw kale. The blender’s action will break down cell walls, allowing myrosinase to convert glucosinolates into ITCs, and you’ll get a full dose of Vitamin C. Or enjoy a vibrant raw kale salad, massaged and dressed, savoring its crisp texture and high Vitamin C content. This is your direct hit of unadulterated, enzyme-rich goodness.

-

The Cooked Comfort: For dinner, perhaps a gently steamed kale side dish, or kale sautéed with garlic and olive oil. Here, you’re enhancing the bioavailability of carotenoids (lutein, zeaxanthin, beta-carotene), reducing oxalates and goitrogens, and making it easier to digest. Remember the trick: chop it, let it rest, then cook it gently, and perhaps sprinkle with some raw mustard powder or a side of raw radishes to reintroduce myrosinase.

-

The Synergistic Harmony: Consider dishes that combine both. A warm lentil and kale salad, where the lentils are cooked and the kale is lightly blanched (to reduce oxalates and tenderize) but still retains some crispness. Or a bowl of hearty soup with cooked kale, topped with a garnish of finely shredded raw kale, providing a dual benefit.

This integrated approach acknowledges the complexities of nutrient interactions and bioavailability. It moves beyond dogmatic adherence to a single method and embraces a more sophisticated understanding of food science and culinary art.

Individual Variability: A Personalized Approach

It’s also crucial to remember that individual responses to food can vary.

- Digestive Sensitivity: If you consistently experience bloating or discomfort with raw kale, leaning more towards cooked preparations is a wise choice. Your body’s ability to extract nutrients from well-digested food is paramount.

- Thyroid Health: While raw kale’s goitrogenic effect is generally minor, individuals with pre-existing thyroid conditions (especially hypothyroidism) might choose to primarily consume cooked kale to minimize any potential interference, ensuring adequate iodine intake.

- Gut Microbiome: Your gut bacteria play a role in converting remaining glucosinolates into ITCs, even if myrosinase is inactivated. A healthy, diverse gut microbiome can pick up some of the slack.

Listen to your body. Experiment with different preparations. What works best for one person might not be ideal for another.

Conclusion: The Kale Compass

My initial rigid stance on raw kale has evolved into a more nuanced, appreciative understanding of this remarkable vegetable. The journey from a simple "either/or" to a sophisticated "both/and" has been an enriching one, revealing the profound wisdom embedded in diverse culinary traditions and cutting-edge nutritional science.

To maximize the health benefits of kale in your diet, the compass points towards intelligent diversity. Embrace the vibrant vitality of raw kale for its enzymatic power and Vitamin C. Appreciate the transformative magic of cooked kale for its enhanced carotenoid bioavailability and reduced anti-nutrients. Employ thoughtful preparation techniques – chopping, resting, strategic cooking, and the ingenious addition of myrosinase-rich companions – to unlock its full spectrum of benefits.

Kale, in all its forms, remains a nutritional superstar. By understanding its intricate chemistry and applying this knowledge in the kitchen, we move beyond mere consumption to a conscious, informed engagement with our food. This isn’t just about eating kale; it’s about mastering the art and science of nourishing ourselves, one vibrant, versatile leaf at a time. The story of kale is a testament to the idea that true health optimization lies not in restrictive dogma, but in a curious, informed, and balanced approach to the incredible bounty of nature.