What Exactly Is Gout? Breaking Down the Uric Acid Crystal Crisis

Imagine a storm, not of wind and rain, but of microscopic, razor-sharp crystals forming within the delicate confines of your joints. Imagine the sudden, excruciating agony, often striking in the dead of night, transforming a healthy limb into a swollen, fiery landscape of unbearable pain. This isn’t a fantasy; it’s the stark reality of a gout attack, a condition that has plagued humanity for millennia, once dubbed the "disease of kings" but now recognized as a democratic affliction, impacting millions across all social strata. Gout is far more than just an inconvenient ache; it is a complex, chronic inflammatory disease, a relentless uric acid crystal crisis that, left unmanaged, can systematically dismantle joint integrity, compromise organ function, and severely diminish quality of life.

To truly understand gout is to embark on a journey into the intricate biochemistry of the human body, to unravel the delicate balance of purine metabolism, and to witness the dramatic consequences when that balance is catastrophically disrupted. It’s a story of an endogenous substance, uric acid, transforming from a benign antioxidant to a crystalline aggressor, triggering an immune response that is both protective and devastating.

The Villain Unmasked: Uric Acid – More Than Just a Waste Product

At the heart of the gout narrative lies uric acid, or urate, its ionized form. For many, the term "uric acid" immediately conjures images of dietary restrictions and joint pain. However, its story is far more nuanced. Uric acid is the final product of purine metabolism in humans. Purines are essential organic compounds found in every cell of our bodies, serving as fundamental building blocks of DNA and RNA, and playing crucial roles in energy transfer (ATP, GTP). They are derived from two primary sources: the natural breakdown of our own cells (endogenous production, accounting for about two-thirds of the total) and the food we consume (exogenous intake).

The metabolic pathway leading to uric acid is a carefully orchestrated series of enzymatic reactions. When purines like adenine and guanine are catabolized, they are converted into hypoxanthine and then xanthine. It is at this critical juncture that the enzyme xanthine oxidase (XO) steps onto the stage. Xanthine oxidase acts as a molecular sculptor, converting hypoxanthine into xanthine, and then xanthine into uric acid. This uric acid then circulates in the blood, awaiting excretion.

Humans are somewhat unique in the animal kingdom in their handling of uric acid. Most mammals possess an enzyme called uricase, which further metabolizes uric acid into allantoin, a much more soluble compound that is easily excreted. However, humans, along with some primates and birds, lost the functional uricase gene millions of years ago through evolutionary mutation. This genetic quirk means we are inherently predisposed to higher circulating levels of uric acid, a physiological characteristic that, while perhaps offering some evolutionary advantages (uric acid is a potent antioxidant), also sets the stage for the crisis of gout.

The Delicate Balance: Production vs. Excretion

Maintaining a healthy serum urate level is a delicate balancing act, a physiological tightrope walk between production and excretion. Approximately two-thirds to three-quarters of the body’s daily uric acid production is handled by the kidneys, which filter and reabsorb urate. The remaining one-third is primarily excreted through the gastrointestinal tract.

The renal handling of uric acid is a complex process involving multiple transporters in the renal tubules. The urate transporter 1 (URAT1), located on the apical membrane of proximal tubular cells, plays a dominant role in reabsorbing filtered urate back into the bloodstream. Other transporters like organic anion transporters (OATs) and ATP-binding cassette transporter G2 (ABCG2) also contribute to both reabsorption and secretion. The balance between these opposing forces dictates how much uric acid ultimately makes it into the urine.

Disruptions to this balance are the fundamental drivers of hyperuricemia, the precursor to gout. Most cases of hyperuricemia (about 90%) are due to underexcretion of uric acid by the kidneys, often influenced by genetic predispositions, renal dysfunction, or certain medications (like thiazide diuretics, which compete for renal transporters). A smaller percentage (about 10%) are "overproducers," whose bodies generate excessive amounts of uric acid, often due to high purine intake, certain hematological malignancies, or rare genetic enzyme deficiencies (e.g., Lesch-Nyhan syndrome).

Hyperuricemia: The Silent Precursor

Hyperuricemia is defined as an abnormally high concentration of uric acid in the blood, typically above 6.8 mg/dL (400 µmol/L) – the physiological saturation point at which monosodium urate (MSU) crystals begin to form in solution at normal body temperature and pH. However, it’s crucial to understand that hyperuricemia is not synonymous with gout. Many individuals live with elevated uric acid levels their entire lives without ever experiencing a gout attack. Asymptomatic hyperuricemia is a silent precursor, a loaded gun, but not yet the shot fired.

The duration and degree of hyperuricemia, along with other contributing factors, determine the likelihood of crystal formation and the subsequent inflammatory cascade. It’s the prolonged saturation and supersaturation of bodily fluids with uric acid that allows MSU crystals to precipitate and deposit in joints and other tissues, setting the stage for the true crisis.

The Crystal Catastrophe: How Urate Crystals Wreak Havoc

The transformation of dissolved uric acid into solid, needle-like crystals is the pivot point of the gout story. These crystals, composed of monosodium urate (MSU), are the physical embodiment of the crisis, the sharp shards that incite the body’s immune system into a destructive frenzy.

Formation and Deposition

The solubility of MSU is temperature and pH dependent. It is less soluble at lower temperatures and lower pH. This explains why the big toe (the first metatarsophalangeal joint, or MTP joint), being one of the coolest parts of the body, is the most common site for the initial gout attack (a phenomenon known as podagra). Other peripheral joints like the ankle, knee, wrist, and elbow are also frequent targets.

Crystal formation isn’t an overnight event. It’s a gradual process, often occurring over years or even decades of sustained hyperuricemia. The crystals initially deposit in avascular tissues like cartilage and within the synovial fluid of joints. They can also accumulate in soft tissues, forming visible lumps called tophi, and even in the kidneys, leading to kidney stones or chronic kidney disease. Trauma, dehydration, rapid changes in uric acid levels (either up or down, such as after starting urate-lowering therapy without prophylactic anti-inflammatory cover), and even minor injuries can all act as triggers, dislodging existing crystals or promoting new formation, thus initiating an acute attack.

The Inflammatory Cascade: Innate Immunity Goes Awry

Once MSU crystals are formed and deposited, they are not passively ignored by the body. They are perceived as a threat, a "danger signal," and trigger a potent inflammatory response, mediated primarily by the innate immune system. This is where the story truly becomes a crisis.

Macrophages and synoviocytes (cells lining the joint capsule) are the first responders. They recognize the MSU crystals as danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) through various receptors, including Toll-like receptors (TLRs). Upon encountering these microscopic shards, the cells attempt to phagocytose (engulf) them. However, the sharp, indigestible nature of the MSU crystals leads to lysosomal rupture within the phagocyte. This cellular damage activates a crucial intracellular protein complex known as the NLRP3 inflammasome.

The NLRP3 inflammasome is a molecular switch for inflammation. Once activated, it recruits and activates caspase-1, an enzyme that acts like a molecular scissor. Caspase-1 then cleaves pro-interleukin-1 beta (pro-IL-1β) into its active form, IL-1β. Interleukin-1 beta is a potent pro-inflammatory cytokine, a signaling molecule that acts as the primary orchestrator of the acute gout attack.

The release of IL-1β into the joint space sets off a cascade of inflammatory events:

- Recruitment of Neutrophils: IL-1β attracts a massive influx of neutrophils, another type of white blood cell, to the affected joint. These neutrophils, in their attempt to clear the crystals, release more inflammatory mediators, including reactive oxygen species and proteases, further damaging tissues and amplifying pain.

- Cytokine Storm: Other pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α (tumor necrosis factor-alpha), IL-6, and IL-8 are also released, intensifying the inflammatory response.

- Vasodilation and Edema: Blood vessels in the affected area dilate, increasing blood flow and causing redness and heat. Fluid leaks from these vessels into the joint space, leading to significant swelling (edema).

- Pain Signaling: The release of prostaglandins, bradykinin, and other pain-mediating substances directly stimulates nerve endings, resulting in the excruciating pain characteristic of a gout attack.

This entire inflammatory cascade is a double-edged sword. While it’s the body’s attempt to neutralize a perceived threat, in the context of gout, it becomes a self-perpetuating cycle of destruction, causing collateral damage to the joint tissues and amplifying the patient’s suffering.

The Clinical Manifestations: A Spectrum of Suffering

Gout is not a monolithic disease; its clinical presentation evolves over time, progressing through distinct stages if left untreated.

Acute Gout Attack (Gouty Arthritis)

The acute gout attack is the most dramatic and unforgettable manifestation of the disease. It typically strikes suddenly and without warning, often in the early hours of the morning. Patients may describe a feeling of vague discomfort or tingling in the joint hours before the full onslaught.

The pain is often described as excruciating, crushing, or burning, reaching its peak intensity within 8-12 hours. The affected joint becomes exquisitely tender, red, hot, and swollen – classic signs of acute inflammation. Even the slightest touch, such as the weight of a bedsheet, can be unbearable. While the big toe is the most common initial site (podagra), gout can affect any joint, including the ankle, knee, wrist, elbow, and even small joints of the hands and feet. Polyarticular attacks (affecting multiple joints simultaneously) are less common but can occur, especially in more advanced cases.

Left untreated, an acute attack typically resolves spontaneously within 7-14 days as the body gradually clears the crystals and the inflammatory response subsides. This self-limiting nature can, paradoxically, be detrimental, as patients may mistakenly believe the problem is gone and neglect long-term management, allowing crystal deposition to continue silently.

Triggers for an acute attack are numerous and varied:

- Dietary excesses: High purine foods (red meat, organ meats, certain seafood like anchovies, sardines), high-fructose corn syrup, and excessive alcohol consumption (especially beer, due to its purine content and ability to increase urate production).

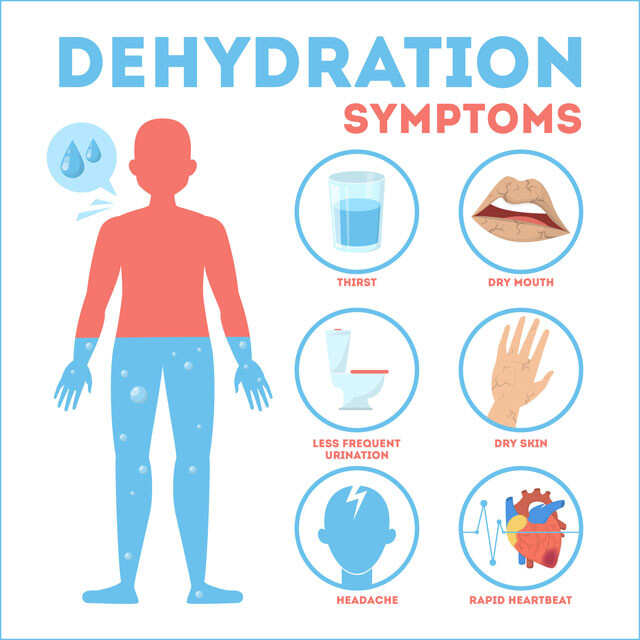

- Dehydration: Concentrates uric acid in the blood.

- Trauma or surgery: Can dislodge crystals or induce local inflammation.

- Rapid changes in serum urate levels: Both increases (e.g., after chemotherapy leading to tumor lysis syndrome) and decreases (e.g., when starting urate-lowering therapy without prophylactic anti-inflammatory medication).

- Certain medications: Thiazide and loop diuretics, aspirin (low dose), cyclosporine, some antituberculosis drugs.

- Illness or stress.

Intercritical Gout

The period between acute attacks is known as intercritical gout. During this phase, the patient is asymptomatic, with no apparent joint pain or inflammation. However, this does not mean the disease is dormant. Microscopic MSU crystals often remain deposited within the joints and soft tissues, continuing their insidious work. The hyperuricemia that led to the initial attack typically persists.

The intercritical period is a critical window for intervention. Without appropriate urate-lowering therapy (ULT), the frequency and severity of attacks tend to increase over time, and the disease can progress to its more chronic, destructive forms.

Chronic Tophaceous Gout

Chronic tophaceous gout represents the advanced stage of the disease, resulting from years of uncontrolled hyperuricemia and recurrent attacks. It is characterized by the formation of tophi – visible or palpable subcutaneous nodules of MSU crystal deposits. Tophi can develop in various locations, most commonly on the ears (helix and antihelix), fingers, toes, elbows (olecranon bursa), and Achilles tendons.

These tophaceous deposits are not merely cosmetic concerns. They can be painful, cause chronic inflammation, and lead to significant joint damage, including bone erosions, cartilage destruction, and ultimately, severe joint deformity and functional impairment. Tophi can also rupture, leading to chalky discharge and increased risk of infection.

Beyond the joints, chronic gout has systemic implications:

- Renal involvement: MSU crystals can deposit in the kidneys, leading to urate nephropathy (chronic interstitial nephritis) and impaired kidney function. Uric acid kidney stones are also a common complication, causing excruciating pain and potential renal obstruction.

- Cardiovascular disease: A strong association exists between gout and an increased risk of hypertension, coronary artery disease, heart failure, and stroke. While hyperuricemia itself may contribute, gout often coexists with other cardiovascular risk factors like metabolic syndrome, obesity, and diabetes, creating a complex web of interconnected pathologies.

Beyond the Joints: Systemic Implications and Comorbidities

The story of gout extends far beyond the confines of the joint. It’s increasingly recognized as a systemic inflammatory disease with profound implications for overall health, often coexisting with a constellation of other chronic conditions.

Cardiovascular Disease

The link between gout, hyperuricemia, and cardiovascular disease (CVD) is robust and bidirectional. Hyperuricemia is frequently observed in patients with hypertension, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and obesity – all major risk factors for CVD. While it’s debated whether hyperuricemia is an independent risk factor for CVD or merely a marker for shared underlying pathologies, there’s growing evidence that uric acid itself may contribute to endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and inflammation, all pathways implicated in atherosclerosis. Patients with gout have a significantly higher risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular mortality.

Renal Disease

The kidneys play a central role in uric acid homeostasis, and conversely, gout can severely impact renal health. Chronic hyperuricemia can lead to urate nephropathy, a form of chronic kidney disease (CKD) characterized by interstitial inflammation and fibrosis caused by MSU crystal deposition within the renal parenchyma. Additionally, uric acid is a major component of kidney stones, which can cause severe pain, recurrent infections, and obstruction, further damaging renal function. The relationship is circular: CKD impairs uric acid excretion, exacerbating hyperuricemia, which in turn can worsen CKD progression.

Metabolic Syndrome and Diabetes

Gout and hyperuricemia are strongly associated with metabolic syndrome, a cluster of conditions including central obesity, hypertension, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia. These conditions share common pathophysiological pathways, often involving chronic low-grade inflammation and oxidative stress. Hyperuricemia has been implicated in the development of insulin resistance, and patients with gout have an elevated risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

Mental Health

Living with a chronic, painful, and often misunderstood disease like gout can take a significant toll on mental well-being. Recurrent, unpredictable attacks can lead to anxiety, depression, and fear of recurrence. The physical disability and pain can impact work, social activities, and overall quality of life, contributing to psychological distress. The historical stigma associated with gout (as a "disease of gluttony") can also lead to feelings of shame and isolation, further complicating patient adherence to treatment.

Diagnosis: Unmasking the Crystal Villain

Accurate diagnosis is paramount in the gout story, as misdiagnosis can lead to inappropriate treatment and prolonged suffering.

Clinical Presentation and History

A detailed patient history, including the characteristics of the pain (sudden onset, peak intensity, resolution), affected joints, and potential triggers, is crucial. Physical examination reveals the classic signs of inflammation: redness, swelling, warmth, and exquisite tenderness of the affected joint.

Serum Urate Levels

While elevated serum urate levels are a prerequisite for gout, a single measurement during an acute attack can be misleading. Urate levels can actually fall during an acute attack due to the inflammatory response, making a normal or even low reading not definitively rule out gout. Therefore, serum urate levels are more useful for diagnosing hyperuricemia and monitoring the effectiveness of urate-lowering therapy, rather than for confirming an acute attack.

Synovial Fluid Analysis: The Gold Standard

The definitive diagnosis of gout rests on the identification of monosodium urate (MSU) crystals in synovial fluid aspirated from the affected joint. This procedure, known as arthrocentesis, is the "gold standard." Under a polarized light microscope, MSU crystals appear as needle-shaped, negatively birefringent crystals. This microscopic confirmation is critical, as other conditions like septic arthritis or pseudogout (calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease, where crystals are rhomboid-shaped and positively birefringent) can mimic gout’s presentation.

Imaging

- X-rays: In early gout, X-rays may be normal. In chronic, untreated gout, they can reveal characteristic "punched-out" erosions with sclerotic overhanging edges ("rat-bite" lesions) and soft tissue swelling, often in periarticular locations.

- Ultrasound: Becoming increasingly valuable, ultrasound can detect MSU crystal deposition even in asymptomatic joints. The "double contour sign" (hyperechoic line over the articular cartilage) and the presence of tophi are highly suggestive of gout.

- Dual-Energy CT (DECT): This advanced imaging technique can specifically identify and quantify urate crystal deposits in joints and soft tissues, offering a non-invasive method for diagnosis and monitoring the efficacy of urate-lowering therapy, particularly useful for patients who cannot undergo arthrocentesis or where clinical diagnosis is challenging.

Management: Taming the Uric Acid Beast

The good news in the story of gout is that it is one of the most treatable forms of arthritis. Effective management involves a two-pronged approach: swiftly managing acute attacks and, more importantly, implementing long-term strategies to lower uric acid levels and prevent future crises.

A. Managing the Acute Attack

The primary goal during an acute attack is rapid pain relief and resolution of inflammation.

- Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs): High-dose NSAIDs (e.g., indomethacin, naproxen, ibuprofen, celecoxib) are typically first-line agents, providing rapid and effective relief. They should be initiated as early as possible.

- Colchicine: This ancient medication (derived from the autumn crocus) is a highly effective anti-inflammatory agent specifically used in gout. It works by inhibiting microtubule polymerization, which interferes with neutrophil migration and phagocytosis of MSU crystals, thus dampening the inflammatory response. It is most effective when taken within 24-36 hours of symptom onset.

- Corticosteroids: Oral corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone) or intra-articular injections (directly into the joint) are powerful anti-inflammatory agents reserved for severe attacks, polyarticular gout, or when NSAIDs and colchicine are contraindicated or ineffective.

- Interleukin-1 (IL-1) Inhibitors: For patients with severe, refractory gout, multiple comorbidities, or contraindications to standard therapies, biologic agents that block IL-1β (e.g., anakinra, canakinumab, rilonacept) can provide rapid and dramatic relief by directly targeting the central cytokine in the inflammatory cascade.

B. Long-Term Management: Urate-Lowering Therapy (ULT)

The cornerstone of long-term gout management is Urate-Lowering Therapy (ULT), aimed at dissolving existing crystals and preventing new ones from forming by maintaining serum urate levels below the saturation point. The target serum urate level is typically less than 6 mg/dL (360 µmol/L), and often less than 5 mg/dL (300 µmol/L) for patients with tophi or frequent attacks.

- Xanthine Oxidase Inhibitors (XOIs): These are the most commonly prescribed ULTs. They reduce uric acid production by inhibiting the enzyme xanthine oxidase.

- Allopurinol: The most widely used XOI, available for decades. It is highly effective but requires careful dose titration, especially in patients with renal impairment, due to the risk of allopurinol hypersensitivity syndrome (a severe, potentially fatal adverse reaction).

- Febuxostat: A newer, non-purine selective XOI. It is an alternative for patients who cannot tolerate allopurinol or for whom allopurinol is contraindicated, particularly in those with moderate renal impairment.

- Uricosurics: These medications work by increasing the renal excretion of uric acid.

- Probenecid: The most common uricosuric. It inhibits the reabsorption of uric acid in the renal tubules, leading to increased urinary excretion. It requires adequate renal function and is generally not suitable for patients who are overproducers of uric acid or have a history of kidney stones.

- Lesinurad: A selective uric acid reabsorption inhibitor (SURI) that was historically used in combination with an XOI. It is no longer available as a standalone drug in the US.

- Pegloticase: This is a recombinant uricase enzyme, administered intravenously. It converts uric acid into allantoin, which is highly soluble and easily excreted. Pegloticase is reserved for severe, refractory chronic tophaceous gout in patients who have failed or are intolerant to other ULTs. It is highly effective but carries a risk of infusion reactions and anaphylaxis, requiring careful monitoring.

Crucially, when initiating ULT, patients should also receive prophylactic anti-inflammatory medication (low-dose colchicine or NSAIDs) for several months. This is because rapid changes in serum urate, even downwards, can mobilize existing crystals and trigger an acute attack.

C. Lifestyle Modifications and Adjunctive Therapies

While not a substitute for ULT, lifestyle modifications play an important supportive role:

- Dietary Advice: Limiting high-purine foods (organ meats, red meat, certain seafood), beverages sweetened with high-fructose corn syrup, and alcohol (especially beer and spirits). However, overly restrictive diets are often unsustainable and insufficient to achieve target urate levels alone.

- Hydration: Drinking plenty of water helps flush uric acid from the body and reduces the risk of kidney stones.

- Weight Management: Obesity is a significant risk factor for hyperuricemia and gout. Gradual weight loss can help lower serum urate levels.

- Medication Review: Reviewing a patient’s entire medication list is essential, as some drugs (e.g., diuretics, low-dose aspirin) can elevate uric acid levels.

- Vitamin C: Some studies suggest a modest urate-lowering effect of vitamin C supplementation.

- Cherries/Cherry Extract: Limited evidence suggests that cherry consumption or cherry extract may help reduce the frequency of gout attacks, possibly due to anti-inflammatory and uricosuric properties.

D. Patient Education and Adherence

A critical, yet often overlooked, component of management is patient education. Patients need to understand that gout is a chronic disease requiring lifelong management, even when they are asymptomatic. Adherence to ULT is paramount to prevent recurrence, dissolve tophi, and protect joints and organs from long-term damage. Breaking down the stigma associated with gout and empowering patients with knowledge about their condition fosters better self-management and improved outcomes.

Living with Gout: A Patient’s Perspective

The story of gout is ultimately a human one. It’s the story of individuals waking up to an unimaginable pain, navigating a complex medical landscape, and often battling societal misconceptions. It’s the story of fear – fear of the next attack, fear of disability, fear of being judged.

For many, the initial diagnosis is a shock, followed by a period of denial or inadequate treatment, leading to a vicious cycle of recurrent attacks and progressive joint damage. The impact on quality of life can be profound, affecting work productivity, recreational activities, and personal relationships. Chronic pain and inflammation can lead to fatigue, frustration, and a sense of hopelessness.

However, the narrative doesn’t have to end in despair. With proper diagnosis, consistent adherence to urate-lowering therapy, and a holistic approach to managing comorbidities and lifestyle, individuals with gout can regain control of their lives. The story transforms from one of relentless crisis to one of proactive management, prevention, and the reclamation of a pain-free, active existence.

Future Directions and Research

The ongoing narrative of gout research continues to seek deeper understanding and more effective solutions. Future directions include:

- Novel Drug Targets: Exploring new pathways for uric acid production, excretion, and inflammation beyond existing medications.

- Personalized Medicine: Utilizing genetic profiling and other biomarkers to predict individual responses to ULTs and tailor treatment strategies.

- Improved Diagnostics: Developing more accurate, non-invasive methods for detecting early crystal deposition and monitoring disease activity.

- Understanding Crystal Dissolution: Research into mechanisms that actively promote the dissolution of existing MSU crystals in tissues.

- Addressing Comorbidities: Better integration of gout management with the treatment of associated conditions like cardiovascular and renal disease.

Conclusion: Beyond the Pain – A Call for Understanding and Action

Gout, the "uric acid crystal crisis," is a formidable adversary, a chronic inflammatory disease that exacts a heavy toll in pain, disability, and systemic health complications. It is a story of biochemistry gone awry, of the body’s own defense mechanisms turning destructive, and of a historical ailment still profoundly impacting modern lives.

Yet, this story is not one without hope. Gout is one of the most successfully treatable forms of arthritis. The knowledge we possess about its pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management offers a clear path to control and remission. The crisis can be averted, the pain silenced, and the progressive damage halted.

The imperative is clear: to move beyond the historical misconceptions and stigma, to recognize gout for the serious, chronic inflammatory disease it is, and to empower patients and healthcare providers with the knowledge and tools necessary for proactive, sustained management. By breaking down the uric acid crystal crisis with understanding, empathy, and consistent action, we can rewrite the narrative for millions, transforming a story of suffering into one of relief, resilience, and renewed quality of life. The battle against the crystal villain is winnable, but it requires vigilance, adherence, and a commitment to comprehensive care.