The Silent Siege: Unmasking Gout’s Devastating Impact on Your Kidneys and Heart

For centuries, gout has been caricatured as the "disease of kings," an affliction of the gluttonous wealthy, manifesting as a searing pain in the big toe. This vivid, albeit oversimplified, image has long overshadowed a far more insidious truth: gout is not merely a joint disorder, but a systemic inflammatory disease with profound, often silent, implications for the body’s most vital organs – the kidneys and the heart. The piercing agony in a swollen joint is but a loud alarm bell, often deafening us to the quiet siege unfolding elsewhere.

Our journey into the lesser-known risks of gout begins with shedding the anachronistic perceptions and embracing a modern understanding. This is a story of how a seemingly localized problem can unravel the intricate balance of human physiology, leading to chronic kidney disease, cardiovascular events, and a significantly diminished quality of life. For the knowledgeable audience, the narrative will delve beyond the superficial, exploring the intricate molecular pathways and physiological disruptions that link a crystal-induced arthritis to the silent, progressive damage of the renal and cardiovascular systems.

Part 1: Gout’s True Nature – A Systemic Provocation

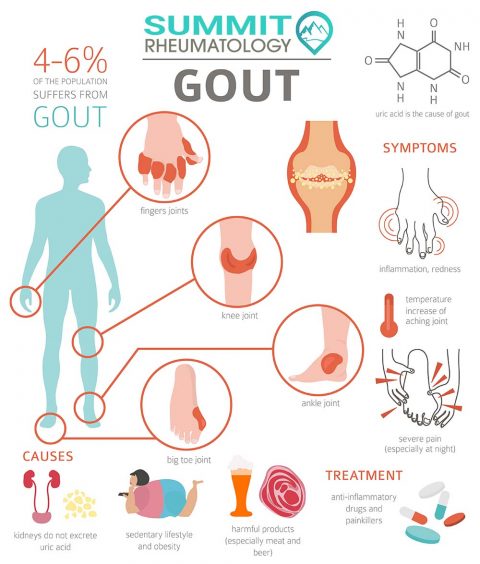

To truly appreciate the systemic threat posed by gout, we must first deconstruct its fundamental nature. Gout is a form of inflammatory arthritis caused by hyperuricemia – persistently elevated levels of uric acid in the blood. When uric acid concentrations exceed their solubility limit, they can precipitate as monosodium urate (MSU) crystals. While these crystals are notorious for triggering acute, agonizing flares in joints, particularly the first metatarsophalangeal joint, their influence extends far beyond mere articular cartilage.

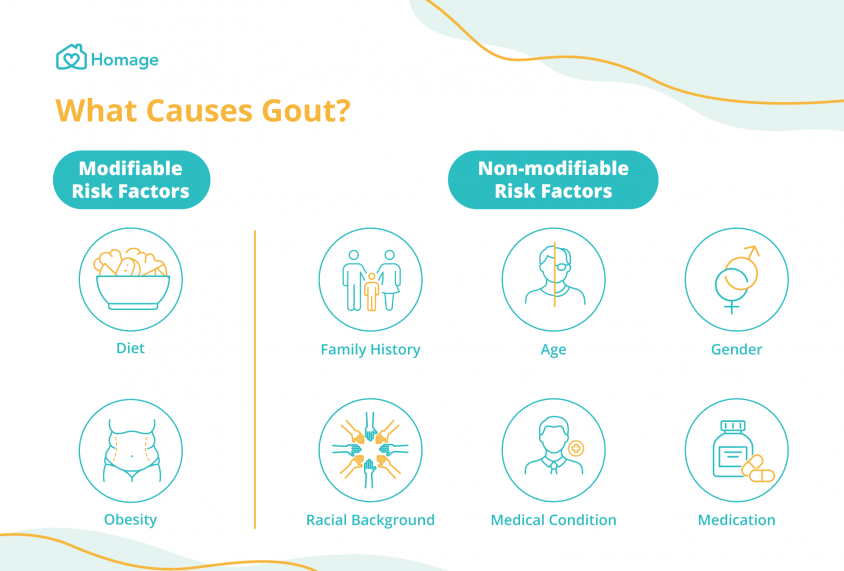

The formation and deposition of MSU crystals are not random events. They are the culmination of a complex metabolic imbalance, often influenced by genetics, diet, lifestyle, and other comorbidities like obesity, hypertension, and metabolic syndrome. What distinguishes gout from other forms of arthritis is its potent activation of the innate immune system. MSU crystals act as "danger signals," recognized by cellular components, most notably the NLRP3 inflammasome. This intracellular protein complex is a crucial mediator of inflammation, responding to various pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). When activated by MSU crystals, the NLRP3 inflammasome initiates a cascade that leads to the proteolytic cleavage and secretion of potent pro-inflammatory cytokines, particularly interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β). It is this robust, uncontrolled IL-1β-driven inflammatory response that fuels the acute pain of a gout flare and, crucially, drives the chronic systemic inflammation that underpins its broader organ damage.

Uric acid itself, even in its soluble form, is no longer considered an inert bystander. While it acts as an antioxidant in the extracellular space, high intracellular concentrations, particularly in vascular and renal cells, can promote oxidative stress. It can inhibit nitric oxide production, a critical molecule for maintaining vascular health, and activate the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), a key regulator of blood pressure and fluid balance. Thus, hyperuricemia, with or without overt gout flares, creates a pro-inflammatory, pro-oxidative, and pro-hypertensive milieu that sets the stage for chronic organ damage. The story of gout, therefore, is not just about crystals in a joint; it is about a profound metabolic derangement that consistently stokes the fires of inflammation and oxidative stress throughout the body.

Part 2: The Silent Siege on the Kidneys – Gout Nephropathy

The kidneys, those tireless filtration organs, play a central role in uric acid homeostasis, being responsible for approximately two-thirds of its excretion. This intimate relationship, however, also makes them particularly vulnerable to the detrimental effects of hyperuricemia and MSU crystal deposition. The story of gout’s impact on the kidneys is one of a multifaceted assault, leading to various forms of renal pathology collectively known as gout nephropathy.

2.1 Uric Acid Nephrolithiasis (Kidney Stones):

One of the most direct and well-understood renal complications of gout is the formation of uric acid kidney stones. Unlike calcium oxalate stones, uric acid stones are often radiolucent, making them harder to detect on standard X-rays. Patients with gout have a significantly higher incidence of kidney stones, often due to persistently acidic urine (pH < 5.5), which reduces the solubility of uric acid, and increased uric acid excretion. The pain of renal colic, the potential for urinary tract obstruction, infection, and progressive renal damage due to recurrent stone formation, represent a tangible and immediate threat to kidney health in gout patients. This is often the first alarm bell for kidney involvement, though it is far from the only one.

2.2 Acute Uric Acid Nephropathy:

While less common, acute uric acid nephropathy is a severe and rapidly progressive form of kidney injury. It typically occurs in situations of massive uric acid overproduction and excretion, such as in tumor lysis syndrome following chemotherapy for certain cancers, or in rare cases of extreme hyperuricemia. In these scenarios, large quantities of uric acid precipitate as crystals within the renal tubules, leading to widespread tubular obstruction and acute kidney injury (AKI). This sudden shutdown of kidney function can be life-threatening and requires immediate intervention, often including aggressive hydration and urate-lowering therapy.

2.3 Chronic Uric Acid Nephropathy and Progression to CKD:

The most insidious and pervasive impact of gout on the kidneys is its contribution to chronic kidney disease (CKD). This is a slow, progressive decline in renal function, often asymptomatic until advanced stages. The mechanisms linking hyperuricemia and gout to CKD are complex and involve both direct and indirect pathways:

- Direct Crystal Deposition: Over time, MSU crystals can deposit not only in the renal tubules but also in the renal interstitium, triggering a chronic inflammatory response. This interstitial inflammation, mediated by IL-1β and other cytokines, leads to the recruitment of immune cells, release of pro-fibrotic factors, and ultimately, renal interstitial fibrosis. This scarring gradually impairs the kidney’s ability to filter waste and maintain fluid and electrolyte balance.

- Endothelial Dysfunction and Renal Ischemia: Elevated uric acid levels contribute to endothelial dysfunction within the renal vasculature. By reducing nitric oxide bioavailability and promoting oxidative stress, uric acid can induce vasoconstriction of renal afferent arterioles, leading to increased renal vascular resistance and reduced renal blood flow. This chronic state of renal ischemia can damage glomeruli and tubules, accelerating nephrosclerosis.

- Activation of the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS): Hyperuricemia has been shown to activate the RAAS, leading to increased angiotensin II production. Angiotensin II is a potent vasoconstrictor and a key driver of hypertension and renal fibrosis. This interaction creates a vicious cycle where high uric acid contributes to hypertension, which in turn further damages the kidneys.

- Oxidative Stress and Inflammation: The generalized systemic inflammation and oxidative stress associated with hyperuricemia directly harm renal cells. Glomerular and tubular cells are exposed to increased reactive oxygen species and inflammatory mediators, leading to cellular injury, apoptosis, and impaired function. The NLRP3 inflammasome, activated by MSU crystals, plays a central role in perpetuating this inflammatory damage within the renal parenchyma.

The bidirectional relationship between gout and CKD is particularly crucial. CKD itself impairs uric acid excretion, leading to worsening hyperuricemia and increasing the risk of gout flares. This creates a challenging clinical scenario where the very condition that causes gout is exacerbated by its complications, making management complex and demanding a nuanced approach to urate-lowering therapy. Patients with gout have a significantly higher risk of developing CKD, and those with both conditions experience a more rapid progression of renal decline, demanding heightened vigilance and aggressive management.

Part 3: The Cardiovascular Connection – Gout as a Cardiac Nemesis

If the kidneys are under silent siege, the heart is often caught in the crossfire, suffering from the collateral damage of chronic inflammation and metabolic derangement. For too long, the association between gout and cardiovascular disease (CVD) was considered merely coincidental, a byproduct of shared risk factors like obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and metabolic syndrome. However, a growing body of evidence now strongly suggests that gout, and hyperuricemia itself, are independent risk factors for CVD, actively contributing to its pathogenesis rather than just being a passive marker. The story here is one of inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and accelerated atherosclerosis, all conspiring to undermine cardiovascular health.

3.1 Endothelial Dysfunction and Hypertension:

The endothelium, the inner lining of blood vessels, is a critical regulator of vascular tone and health. Hyperuricemia significantly impairs endothelial function. Soluble uric acid can reduce the bioavailability of nitric oxide (NO), a powerful vasodilator and anti-atherogenic molecule. This leads to impaired vasodilation, increased vascular stiffness, and elevated systemic blood pressure. Furthermore, uric acid can activate the RAAS, contributing to hypertension through multiple mechanisms, including renal vasoconstriction and increased sodium reabsorption. Chronic hypertension, a direct consequence and exacerbator of hyperuricemia, is a major risk factor for heart disease and stroke. The sustained inflammatory state in gout further damages the delicate endothelial lining, creating a fertile ground for atherosclerotic plaque formation.

3.2 Acceleration of Atherosclerosis:

Atherosclerosis, the hardening and narrowing of arteries due to plaque buildup, is the root cause of most cardiovascular events. Gout and hyperuricemia accelerate this process through several pathways:

- Chronic Inflammation: The persistent, low-grade systemic inflammation characteristic of gout, driven by IL-1β and other cytokines, directly promotes atherosclerotic plaque development and instability. Inflammatory mediators attract immune cells to the arterial wall, where they contribute to lipid accumulation, smooth muscle cell proliferation, and extracellular matrix remodeling – all hallmarks of atherosclerosis.

- Oxidative Stress: High levels of uric acid contribute to systemic oxidative stress. Reactive oxygen species can oxidize low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, making it more atherogenic and easily taken up by macrophages, forming foam cells that contribute to plaque growth.

- Platelet Activation: Uric acid has been shown to promote platelet aggregation, increasing the risk of thrombotic events such as myocardial infarction and stroke.

- Smooth Muscle Cell Proliferation: Hyperuricemia can stimulate the proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells, contributing to the thickening and stiffening of arterial walls.

3.3 Myocardial Remodeling and Heart Failure:

The heart muscle itself is not immune to gout’s systemic reach. Chronic inflammation and hypertension, both intimately linked to gout, can lead to adverse myocardial remodeling. This involves structural and functional changes in the heart, such as left ventricular hypertrophy (enlargement of the heart’s main pumping chamber), increased stiffness, and impaired relaxation (diastolic dysfunction). These changes reduce the heart’s pumping efficiency and can progress to overt heart failure. Studies have shown that patients with gout have a significantly higher risk of developing heart failure, both with preserved and reduced ejection fraction. The ongoing inflammatory state may also directly contribute to myocardial fibrosis, further impairing cardiac function.

3.4 Arrhythmias and Cardiac Events:

Beyond structural damage, gout has been linked to an increased risk of cardiac arrhythmias, particularly atrial fibrillation. The chronic inflammatory burden and alterations in cardiac structure can create an arrhythmogenic substrate. Ultimately, the cumulative effect of endothelial dysfunction, accelerated atherosclerosis, hypertension, and myocardial remodeling manifests as a significantly elevated risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), including myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular mortality in patients with gout. This isn’t merely a statistical correlation; it’s a testament to a shared pathological foundation where gout acts as a potent accelerant.

Part 4: The Vicious Cycle – Kidney, Heart, and Gout Intertwined

The narrative of gout’s systemic impact is not linear; it is a complex tapestry woven with interconnected threads of pathology. The damage inflicted upon the kidneys and heart is not isolated but rather forms a vicious cycle, where each organ’s dysfunction exacerbates the others, further entrenching the disease and making management increasingly challenging.

Imagine a patient who has been managing gout flares for years. Over time, the chronic hyperuricemia and intermittent inflammation begin to take their toll on the kidneys, leading to a gradual decline in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and the onset of CKD. As kidney function deteriorates, the body’s ability to excrete uric acid diminishes, leading to even higher serum urate levels. This worsens the hyperuricemia, increasing the frequency and severity of gout flares, and further accelerating kidney damage.

Simultaneously, the evolving CKD contributes to the development and worsening of hypertension. The damaged kidneys struggle to regulate blood pressure, leading to fluid retention and activation of the RAAS. This elevated blood pressure places an increased workload on the heart, promoting left ventricular hypertrophy and myocardial remodeling. The systemic inflammation, already fueled by gout, is further exacerbated by the presence of CKD, creating a pro-atherogenic environment that accelerates coronary artery disease.

Now, consider the impact on the heart. If the patient develops heart failure, the impaired cardiac output reduces blood flow to the kidneys, further compromising their function (cardio-renal syndrome). This reduction in renal perfusion can lead to further increases in serum uric acid, closing the loop and intensifying the inflammatory burden on both organs. The medications used to manage heart failure or CKD can also sometimes interact with uric acid metabolism or require dose adjustments in the presence of renal impairment, complicating therapeutic strategies for gout.

The common denominator in this intricate interplay is chronic inflammation. The NLRP3 inflammasome, initially activated by MSU crystals in the joint, is now understood to be a key player in the pathogenesis of CKD, hypertension, atherosclerosis, and heart failure, even in the absence of overt gout flares. This shared inflammatory pathway explains how the "disease of kings" can orchestrate such widespread systemic damage. Understanding this intricate web of interactions is crucial for healthcare providers and patients alike, as it underscores the necessity of a holistic and integrated approach to managing gout, rather than simply addressing the symptomatic joint pain. Ignoring one piece of the puzzle inevitably leads to the unraveling of the entire physiological system.

Part 5: Breaking the Cycle – Strategies for Mitigation and Management

Given the profound and widespread implications of gout on kidney and heart health, a proactive and comprehensive management strategy is paramount. This is where the story shifts from diagnosis and pathology to intervention and hope, emphasizing that while the risks are significant, they are not insurmountable.

5.1 Aggressive Urate-Lowering Therapy (ULT):

The cornerstone of gout management, and indeed the primary strategy for mitigating its systemic risks, is aggressive and sustained urate-lowering therapy. The goal is to achieve and maintain a serum uric acid level below 6 mg/dL (and often even lower, below 5 mg/dL, in patients with established tophaceous gout or significant comorbidities like CKD).

- Pharmacological Interventions:

- Xanthine Oxidase Inhibitors (XOIs): Allopurinol and Febuxostat are the first-line agents. They reduce uric acid production. Allopurinol is generally well-tolerated, but dose adjustments are crucial in CKD patients to prevent toxicity. Febuxostat, while not requiring dose adjustment in mild-to-moderate CKD, has had some cardiovascular safety concerns in certain patient populations, necessitating careful consideration, especially in those with pre-existing CVD.

- Uricosurics: Probenecid increases uric acid excretion via the kidneys. It is less effective in patients with moderate-to-severe CKD and should be used with caution in those with a history of kidney stones.

- Pegloticase: A pegylated recombinant uricase, this intravenous therapy is reserved for severe, refractory chronic tophaceous gout, particularly in patients who have failed other therapies. It rapidly lowers uric acid levels but is associated with a high risk of infusion reactions and antibody formation.

- Other Agents: Losartan (an ARB for hypertension) and fenofibrate (for dyslipidemia) have mild uricosuric effects and can be beneficial in patients with comorbid conditions.

The decision to initiate ULT, particularly in asymptomatic hyperuricemia, remains a subject of ongoing debate, but the growing evidence linking hyperuricemia to kidney and heart damage increasingly supports earlier intervention, especially in high-risk individuals with comorbidities. The narrative must stress that ULT is not just for preventing flares; it is for preventing organ damage.

5.2 Lifestyle Modifications:

Pharmacology alone is rarely sufficient. Lifestyle interventions play a critical role in both managing gout and mitigating its systemic risks:

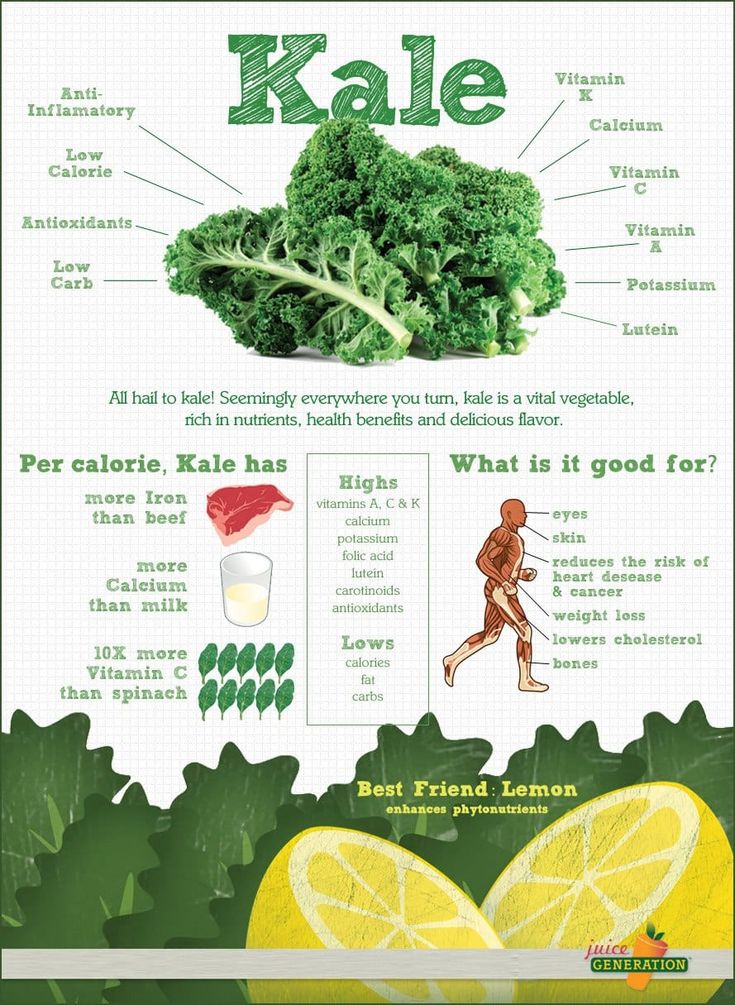

- Dietary Adjustments: Reducing intake of high-purine foods (red meat, organ meats, some seafood), high-fructose corn syrup, and sugary drinks is essential. Moderate alcohol consumption, especially beer, should be limited. A plant-rich diet, low-fat dairy, and cherries have shown beneficial effects.

- Weight Management: Obesity is a significant risk factor for hyperuricemia, gout, and both kidney and heart disease. Achieving and maintaining a healthy weight through diet and exercise can profoundly impact all three conditions.

- Hydration: Adequate fluid intake (primarily water) helps promote uric acid excretion and reduces the risk of kidney stone formation.

- Regular Exercise: Physical activity improves cardiovascular health, aids in weight management, and can indirectly help lower uric acid levels.

- Smoking Cessation: Smoking is a major risk factor for CVD and can exacerbate systemic inflammation.

5.3 Integrated Care Approach:

The multifaceted nature of gout’s impact necessitates a collaborative and integrated approach to patient care. Rheumatologists, nephrologists, cardiologists, and primary care physicians must work in concert.

- Screening and Monitoring: Regular monitoring of kidney function (eGFR, proteinuria) and cardiovascular risk factors (blood pressure, lipids, glucose) is crucial for all gout patients.

- Patient Education: Empowering patients with knowledge about the systemic risks of gout beyond joint pain is vital. Understanding the link to kidney and heart health can motivate adherence to ULT and lifestyle changes.

- Management of Comorbidities: Aggressive management of co-existing conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and metabolic syndrome is integral to protecting the kidneys and heart.

5.4 Future Directions:

Research continues to uncover new facets of gout’s pathophysiology and potential therapeutic targets. The development of novel IL-1β inhibitors, while currently used for acute flares, holds promise for addressing the chronic inflammatory burden. Deeper understanding of the NLRP3 inflammasome and its role in various organ systems may lead to more targeted therapies that can simultaneously protect joints, kidneys, and the heart. The story of gout management is still being written, but the current chapter emphasizes a proactive, comprehensive strategy.

Conclusion: Reclaiming Health from the Shadows of Gout

The journey through the intricate world of gout’s lesser-known risks reveals a disease far more complex and dangerous than its common perception suggests. What begins as an agonizing joint pain can, if left unmanaged or inadequately treated, silently erode the health of the kidneys, leading to chronic kidney disease, and relentlessly attack the cardiovascular system, increasing the risk of heart failure, stroke, and premature death. The narrative of gout is a compelling illustration of how localized inflammation can trigger systemic pathology, demonstrating the interconnectedness of our body’s vital systems.

For the knowledgeable audience, the intricate dance between hyperuricemia, MSU crystals, the NLRP3 inflammasome, chronic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and the resulting renal and cardiovascular damage paints a stark picture. It underscores the critical need to move beyond symptomatic relief and embrace a holistic, aggressive management strategy for gout.

The silent siege on the kidneys and heart is not inevitable. By recognizing gout as a systemic disease, by actively pursuing sustained urate-lowering, by advocating for comprehensive lifestyle modifications, and by fostering an integrated care approach, we can break the vicious cycle. We can transform the story of gout from one of progressive organ damage to one of proactive protection and improved long-term health. The time has come to unmask gout for what it truly is: a formidable systemic threat that demands our full attention and a commitment to comprehensive care, ensuring that the agony of the big toe does not lead to the silent sorrow of a failing heart and kidneys.