The Silent Siege: Why Gout Loves Your Big Toe (and Other Joints) – A Podiatrist’s Chronicle

The patient hobbles in, face contorted, each step a testament to agonizing pain. His big toe, the very joint designed for the elegant propulsion of human locomotion, is a swollen, angry, crimson caricature of its former self. It pulsates with a heat so intense it radiates through the room, a throbbing beacon of distress. This, I think to myself, is the quintessential arrival of gout – a condition often misunderstood, frequently mismanaged, and universally underestimated in its capacity for agony.

As a podiatrist, the big toe, or the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint, is my daily canvas. It’s where I see the most dramatic manifestations of this insidious disease, but it’s also where the story of gout often begins, though rarely ends. Why this particular joint? Why does gout, with its ancient lineage and modern prevalence, so often choose this seemingly unassuming digit as its primary battleground? The answer, like much in medicine, is a complex tapestry woven from biochemistry, biomechanics, evolutionary quirks, and environmental factors.

The Scene of the Crime: The Big Toe – An Evolutionary Marvel, a Biochemical Target

Let’s begin with the big toe itself. Anatomically, it’s a marvel of engineering. The first MTP joint is crucial for balance, propulsion during gait, and absorbing significant forces with every step. It’s a workhorse, bearing up to twice the body weight during walking and even more during running or jumping. This constant mechanical stress, this microtrauma inherent in its function, is one of the subtle predisposing factors. Think of it as a continually agitated landscape, primed for invasion.

Beyond its mechanical role, the big toe exists at the periphery of our circulatory system. It’s a ‘cooler’ joint, literally. Our core body temperature is meticulously regulated at around 37°C, but extremities, especially the toes, are often several degrees cooler. This seemingly minor physiological detail is, in fact, a profound chemical trigger. Uric acid, the metabolic culprit behind gout, has a temperature-dependent solubility. As the temperature drops, its solubility decreases, making it more prone to precipitating out of solution and forming those infamous, razor-sharp monosodium urate (MSU) crystals. The big toe, often exposed, often cooler, becomes a prime crystallization chamber.

Furthermore, the big toe, like other peripheral joints, is less vascularized compared to central joints. While this might seem counterintuitive for a workhorse joint, the reduced blood flow can mean slower clearance of accumulating uric acid. It’s like a stagnant pool where sediment can settle more easily. Combine this with the everyday microtrauma that can create microscopic tears and inflammatory responses, and you have a perfect storm brewing in a relatively isolated, cooler environment.

The Culprit: Uric Acid – A Double-Edged Sword

To truly understand why gout loves the big toe, we must first understand its nemesis: uric acid. Uric acid is not inherently evil. It’s a natural byproduct of purine metabolism. Purines are essential components of our DNA and RNA, and they’re found in the foods we eat (red meat, shellfish, certain vegetables) and produced endogenously by our bodies. Uric acid also acts as a potent antioxidant, playing a beneficial role in protecting our cells from damage. The problem arises when its levels become too high – a condition known as hyperuricemia.

Hyperuricemia is the foundational precursor to gout. It’s defined as a serum uric acid level exceeding 6.8 mg/dL (or 400 µmol/L), the physiological saturation point at normal body temperature. Above this threshold, uric acid begins to supersaturate the blood, much like sugar in an over-sweetened tea. While not everyone with hyperuricemia develops gout, it is an absolute prerequisite.

The balance of uric acid in the body is delicate. Approximately two-thirds of uric acid is excreted by the kidneys, and one-third by the intestines. Any disruption in this balance – either through overproduction of uric acid (less common, often genetic or related to certain medical conditions/medications) or, more frequently, underexcretion by the kidneys – leads to its accumulation. Genetic predispositions play a significant role here, with variants in genes like SLC2A9 and ABCG2 affecting uric acid transporters in the kidneys and gut, making some individuals inherently less efficient at clearing it.

So, we have an excess of uric acid circulating in the bloodstream. It’s dissolved, silent, a ticking time bomb. But it needs a trigger, a nucleation point, to unleash its destructive power.

The Weapon: Monosodium Urate Crystals – Microscopic Shards of Glass

When uric acid levels remain persistently high, especially in cooler, less vascularized environments, it precipitates out of solution and forms MSU crystals. These aren’t benign, soft aggregates. They are microscopic, needle-shaped structures, sharp and formidable. Imagine countless tiny shards of glass, silently forming within the joint capsule, cartilage, and surrounding tissues.

For a long time, these crystals can lie dormant, a "silent siege" within the joint. Patients might be hyperuricemic for years, even decades, without experiencing a single gout attack. This asymptomatic hyperuricemia is the prelude, the calm before the storm. The question then becomes: what triggers the acute attack? What ignites the biological inferno?

Triggers are varied and often involve a sudden fluctuation in uric acid levels, either up or down. A celebratory feast rich in purines and alcohol, dehydration, certain medications (like diuretics), trauma to the joint (remember the big toe’s mechanical stress?), or even a rapid drop in uric acid levels due to initiating urate-lowering therapy too aggressively can all precipitate an attack. The mechanism is thought to involve the shedding of existing crystals into the joint space or the rapid formation of new ones.

Once these crystals are released or formed, they are recognized by the body’s innate immune system as foreign invaders. Macrophages and other immune cells attempt to engulf them, but the sharp crystals rupture the cell membranes, releasing potent pro-inflammatory mediators. This process activates a crucial intracellular complex called the "NLRP3 inflammasome," which, in turn, leads to the massive production and release of interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) – a master cytokine that orchestrates an intense inflammatory cascade.

The Explosion: The Acute Gout Attack – A Biological Inferno

The acute gout attack is a spectacle of inflammation. The big toe, or any affected joint, becomes exquisitely painful, tender to the lightest touch, even the weight of a bedsheet. It swells dramatically, turns red or purple, and feels searingly hot. This isn’t just pain; it’s an all-encompassing agony that incapacitates. Patients often describe it as the worst pain they have ever experienced, a sensation of the joint being on fire, crushed, or impaled.

The inflammatory response is swift and brutal. Neutrophils, the body’s first responders, flood the joint, attempting to clear the crystals. But their efforts often exacerbate the problem, releasing more inflammatory chemicals and causing further tissue damage. The cycle feeds itself, building to a crescendo of pain and swelling that typically peaks within 12-24 hours and can last for several days to weeks if untreated.

From my perspective in the clinic, the presentation is almost unmistakable. The sudden onset, often at night, waking the patient from sleep. The unilateral involvement (though polyarticular attacks can occur). The patient’s inability to bear weight. The exquisite tenderness. These are the hallmarks. Yet, I’ve seen countless patients, often stoic and resistant to seeking medical help, attribute it to a sprain, a stubbed toe, or even an infection, delaying crucial diagnosis and treatment.

The Investigation: A Podiatrist’s Diagnostic Lens

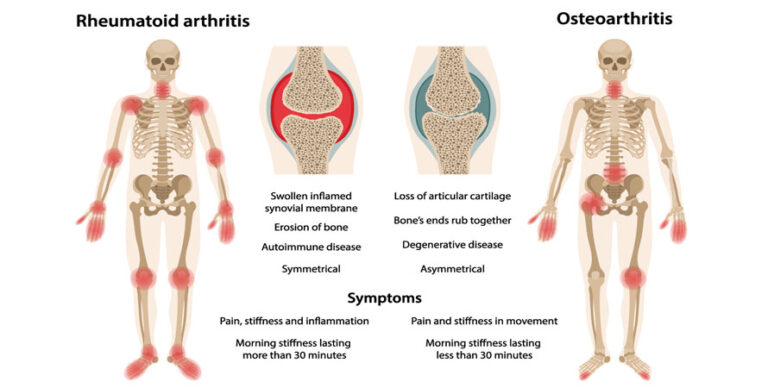

My role in diagnosing gout is often pivotal. While other conditions like cellulitis, septic arthritis, or pseudogout (calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease) can mimic gout, the clinical picture, combined with my specialized knowledge of foot and ankle pathology, usually guides me swiftly.

Clinical Assessment: The story is key. A sudden, agonizing onset of monoarticular arthritis, particularly in the first MTP joint, in a patient with risk factors (male, middle-aged or older, obesity, hypertension, kidney disease, alcohol consumption, certain medications) immediately raises suspicion. I look for the characteristic signs: erythema, warmth, swelling, and severe tenderness.

Laboratory Tests: Blood tests for serum uric acid levels are a common first step. However, it’s crucial to understand that during an acute attack, uric acid levels can actually be normal or even low, as the body attempts to clear the crystals. Therefore, a normal uric acid level during an acute flare does not rule out gout. It’s more indicative when taken after the acute inflammation has subsided. Other tests, like complete blood count and inflammatory markers (ESR, CRP), will typically show elevated signs of systemic inflammation.

Imaging: X-rays are often normal in early gout but can show soft tissue swelling. Over time, in chronic untreated gout, characteristic "punched-out" erosions with sclerotic margins, often with an overhanging edge, can appear. Ultrasound is increasingly valuable, revealing the "double contour sign" (hyperechoic line over the articular cartilage, representing MSU crystal deposition) and "snowstorm appearance" within the joint fluid, indicative of crystals. Dual-energy CT (DECT) is the most sensitive imaging modality, capable of detecting MSU crystals even in asymptomatic joints, though it’s not typically a first-line diagnostic tool.

The Gold Standard: Joint Aspiration: The definitive diagnosis of gout is made by aspirating synovial fluid from the affected joint and identifying negatively birefringent, needle-shaped MSU crystals under polarized light microscopy. This is a procedure I frequently perform, not just for diagnosis but also to rule out septic arthritis, a much more urgent and potentially limb-threatening condition that can co-exist with gout. The ability to differentiate these conditions quickly is paramount.

The First Aid: Quelling the Inferno

Once diagnosed, the immediate priority is to extinguish the biological fire. Acute gout attacks are treated with anti-inflammatory medications.

- Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs): These are often the first-line treatment, reducing pain and inflammation rapidly. Indomethacin, naproxen, and ibuprofen are commonly used. However, they must be used cautiously in patients with kidney disease, heart failure, or a history of gastrointestinal bleeding.

- Colchicine: An ancient remedy, colchicine works by inhibiting neutrophil migration and activation, thus disrupting the inflammatory cascade. It’s most effective when taken within the first 24-36 hours of an attack and can be used at lower doses for prophylaxis against future attacks. Side effects, particularly gastrointestinal distress, can limit its use.

- Corticosteroids: Oral prednisone or intra-articular corticosteroid injections (which I administer directly into the affected joint) are powerful anti-inflammatory agents, particularly useful when NSAIDs are contraindicated or when the attack is severe and refractory. They provide rapid relief but carry their own set of side effects with long-term use.

My approach often involves a combination, tailored to the patient’s individual health profile and the severity of the attack. But I always emphasize that treating the acute attack is just symptom management; it does not address the underlying cause.

The Long War: Managing the Chronic Threat

The true battle against gout is fought not in the acute phase, but in the long term, through careful management of hyperuricemia. This is where the narrative shifts from crisis intervention to chronic disease management, and where patient education and adherence become critical.

Urate-Lowering Therapy (ULT): The goal of ULT is to reduce serum uric acid levels below the saturation point (typically <6 mg/dL, or even lower, <5 mg/dL, for patients with tophi or frequent attacks) to prevent crystal formation and dissolve existing crystals.

- Xanthine Oxidase Inhibitors (XOIs): Allopurinol and febuxostat are the most commonly prescribed ULTs. They work by blocking xanthine oxidase, an enzyme involved in uric acid production. Allopurinol is generally the first choice, but febuxostat is an alternative for patients who cannot tolerate allopurinol or have renal impairment.

- Uricosurics: Probenecid works by increasing the excretion of uric acid by the kidneys. It’s typically used in patients who are underexcretors of uric acid and have good kidney function.

- Pegloticase: For severe, refractory chronic gout with significant tophi that doesn’t respond to conventional ULT, pegloticase is a powerful intravenous enzyme that converts uric acid into allantoin, a more soluble compound that is easily excreted. It’s a game-changer for some, but carries risks, including infusion reactions and anaphylaxis.

Initiating ULT is a delicate process. Paradoxically, lowering uric acid too quickly can precipitate an acute attack, as existing crystals are destabilized. Therefore, ULT is usually started after an acute attack has resolved, and often with concurrent prophylactic low-dose colchicine or NSAIDs for several months to prevent flares during the initial phase.

Adherence to ULT is a significant challenge. Patients often stop their medication once the pain subsides, failing to understand that gout is a chronic disease, not just a series of acute attacks. This is where my storytelling and patient education skills are put to the test – explaining the long-term consequences of uncontrolled hyperuricemia, the slow but relentless damage wrought by persistent crystals, and the importance of lifelong therapy.

Beyond the Big Toe: The Systemic Nature of Gout

While the big toe is the poster child for gout, it’s crucial to remember that gout is a systemic disease. Urate crystals can deposit in virtually any joint, though other common sites include the midfoot, ankle, knee, wrist, and small joints of the hands. I’ve seen bizarre presentations – gout in the shoulder, the elbow, even the spine.

Beyond the joints, uric acid crystals can deposit in soft tissues, forming chalky nodules called tophi. These are pathognomonic for chronic gout and represent massive accumulations of MSU crystals. Tophi are often seen on the helix of the ear, around the finger joints, on the olecranon bursa of the elbow, or on the Achilles tendon. On the feet, they can form large, deforming masses, particularly around the MTP joints, causing chronic pain, joint destruction, skin ulceration, and infection. These require careful surgical debridement or excision in some cases, often performed by a podiatrist.

More insidiously, gout is increasingly recognized as a metabolic disease with significant comorbidities. Patients with gout have a higher risk of:

- Kidney Stones: Uric acid stones can form in the kidneys.

- Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD): Persistent hyperuricemia and recurrent gout attacks can contribute to renal damage.

- Cardiovascular Disease: Gout is independently associated with an increased risk of hypertension, myocardial infarction, stroke, and heart failure.

- Metabolic Syndrome: There’s a strong link between gout, obesity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and hypertension.

This broader perspective underscores the importance of a holistic approach to gout management, often involving a multidisciplinary team including rheumatologists, nephrologists, and primary care physicians, with the podiatrist playing a key role in local joint management and early diagnosis.

Prevention and Lifestyle: Empowering the Patient

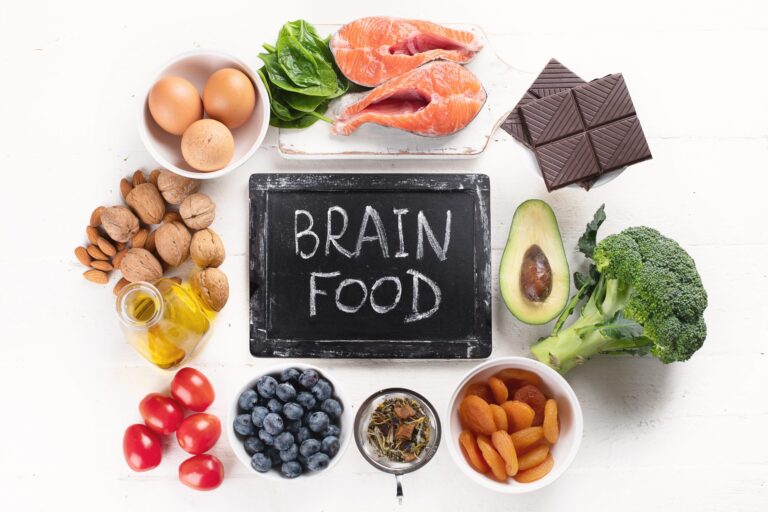

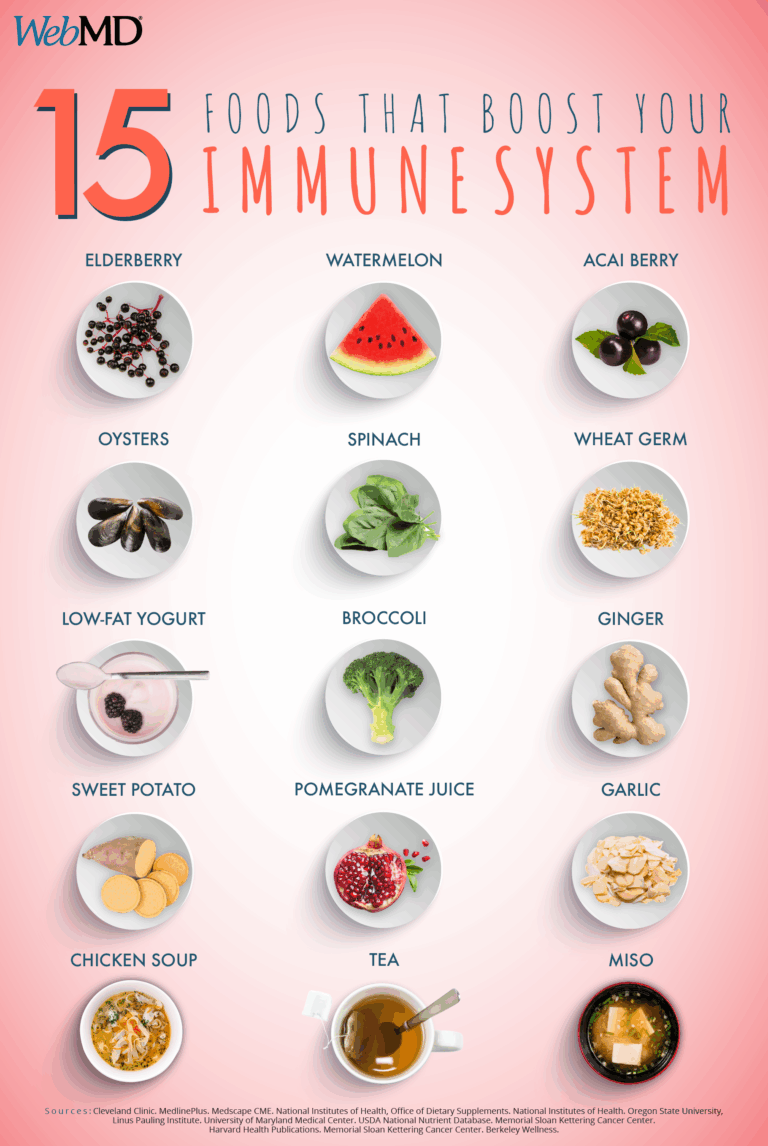

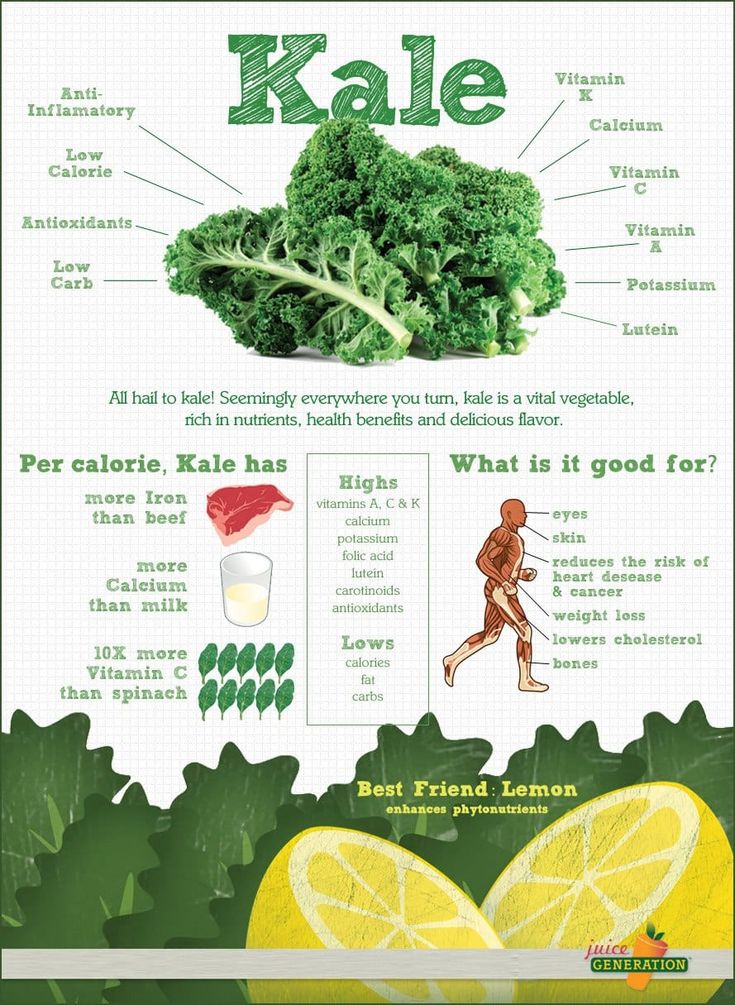

While genetics play a significant role, lifestyle modifications can profoundly impact gout management and prevention. As a podiatrist, I often find myself delving into nutritional counseling and general health advice.

- Dietary Modifications: Reducing consumption of high-purine foods (red meat, organ meats, shellfish) and foods high in fructose (sugary drinks, processed foods) can help. However, it’s a misconception that diet alone can cure gout; for most, it’s an adjunct to medication.

- Alcohol: Beer and spirits are particularly problematic due to their purine content and impact on uric acid excretion. Wine appears to have a lesser effect. Moderation or abstinence is often recommended.

- Hydration: Drinking plenty of water helps the kidneys excrete uric acid.

- Weight Management: Obesity is a significant risk factor. Gradual, sustainable weight loss can improve uric acid levels and overall metabolic health.

- Medication Review: Certain medications, like diuretics (thiazides, loop diuretics), aspirin (low dose), and niacin, can elevate uric acid levels. A careful review with the prescribing physician is essential.

The Podiatrist’s Unique Perspective: Guardians of the Gait

My perspective as a podiatrist on gout is unique. I am often the first point of contact for a patient in excruciating pain, the one who literally sees the immediate impact of the disease. My hands touch the inflamed joint, my eyes witness the dramatic presentation. I understand the biomechanical implications of a compromised big toe – the limp, the compensatory movements, the fear of movement itself.

I am also keenly aware of the long-term consequences in the feet: the slow, relentless destruction of cartilage, the development of painful tophi that deform the foot and challenge footwear, the increased risk of infection from skin breakdown over large tophaceous deposits. I often manage the chronic foot pain, the footwear challenges, and, when necessary, the surgical intervention for debilitating tophi or severe joint damage.

My role extends beyond diagnosis and acute treatment. It encompasses patient education, empowering them with the knowledge to manage their chronic condition. It involves guiding them through lifestyle changes, advocating for consistent ULT, and collaborating with their other healthcare providers to ensure a comprehensive, integrated approach to this complex, systemic disease.

The Unwritten Chapters: Future Directions

The story of gout is still being written. Research continues to explore the nuances of uric acid metabolism, the intricate pathways of inflammation, and the genetic predispositions that make some individuals more susceptible. Newer, more targeted therapies are emerging, offering hope for those whose gout remains challenging to control. Personalized medicine, tailored to an individual’s genetic profile and metabolic pathways, may one day offer even more effective prevention and treatment strategies.

But for now, the narrative remains consistent: gout is a formidable foe, and its favorite target, the big toe, stands as a stark reminder of its destructive power. My commitment, as a podiatrist, is to continue to be at the forefront of this battle, alleviating pain, preventing disability, and empowering my patients to reclaim their mobility and their lives from the silent, insidious siege of uric acid. It is a story of science and suffering, but also of hope, vigilance, and the profound impact of timely, informed care.