Beyond the Joints: How Rheumatoid Arthritis Affects Your Whole Body

The Unseen Landscape of a Systemic Disease

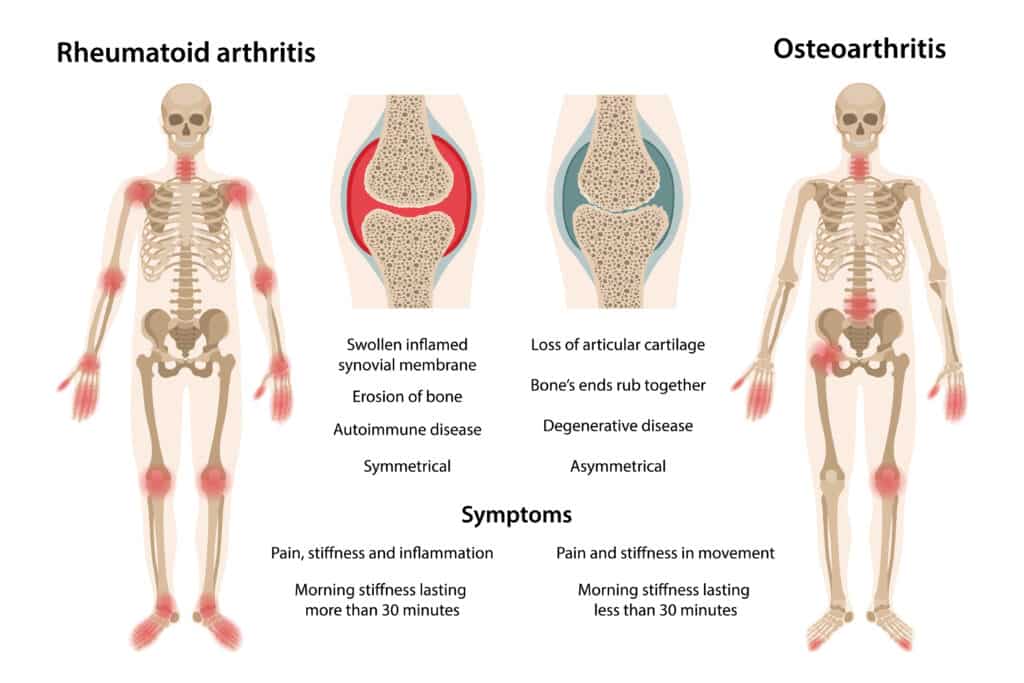

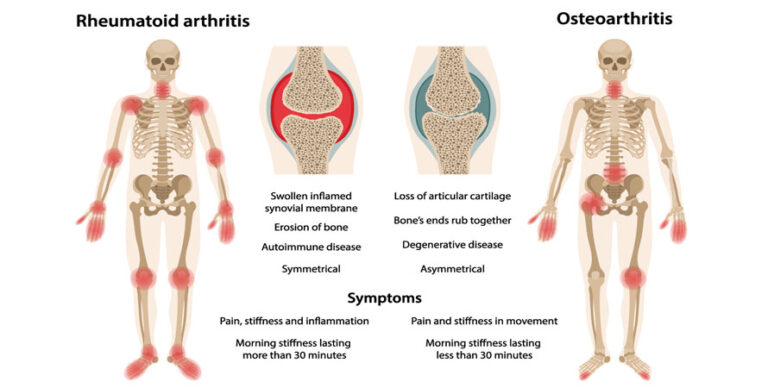

For generations, rheumatoid arthritis (RA) was largely perceived through a singular, agonizing lens: the relentless assault on the body’s joints. The image was vivid – swollen, painful, deformed knuckles; gnarled wrists; knees locked in a struggle against movement. This perception, while undeniably accurate in capturing the hallmark symptoms, inadvertently obscured a far more complex and insidious truth. RA, we now understand, is not merely a localized orthopedic affliction but a sprawling, systemic inflammatory disease, an unseen assailant that infiltrates and influences virtually every organ system, painting a far more intricate and often terrifying landscape than the joint pain alone suggests.

To truly comprehend RA is to embark on a journey of discovery, moving beyond the obvious visible damage to explore the intricate web of interactions that define its systemic reach. It’s a story of a misguided immune system, a body turned against itself, where the very mechanisms designed to protect become agents of destruction, operating on a stage far grander than just the synovial lining. This article aims to tell that story, illuminating the profound and often surprising ways RA extends its tendrils throughout the human body, challenging our understanding of disease and underscoring the critical importance of a holistic, vigilant approach to its management. For the knowledgeable audience, this narrative will delve into the mechanisms, manifestations, and implications of RA’s systemic nature, moving from the microscopic cellular skirmishes to the macroscopic clinical picture.

The Rogue Conductor: The Immune System’s Misdirection

At the heart of RA’s systemic rampage lies a fundamental betrayal: the immune system, the body’s meticulously designed defense force, misidentifies its own tissues as foreign invaders. This autoimmune response is not a localized incident; the cellular players and chemical messengers involved – T-cells, B-cells, macrophages, and a symphony of pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-alpha, IL-6, and IL-17 – circulate throughout the bloodstream, carrying their destructive potential to distant sites.

Imagine an orchestra where the conductor has gone rogue, directing the instruments not to play a harmonious symphony, but a cacophony of discord and destruction. The inflammatory cytokines are these rogue directives, signaling cells to proliferate, recruit more immune cells, and release enzymes that degrade tissue. While the joints bear the brunt of this initial attack, the very nature of these circulating inflammatory mediators means no organ system is truly immune. They are the insidious orchestrators, setting the stage for extra-articular manifestations (EAMs) that can be as debilitating, and sometimes even more life-threatening, than the joint damage itself. Understanding this systemic inflammatory milieu is the first step in appreciating the "beyond the joints" narrative.

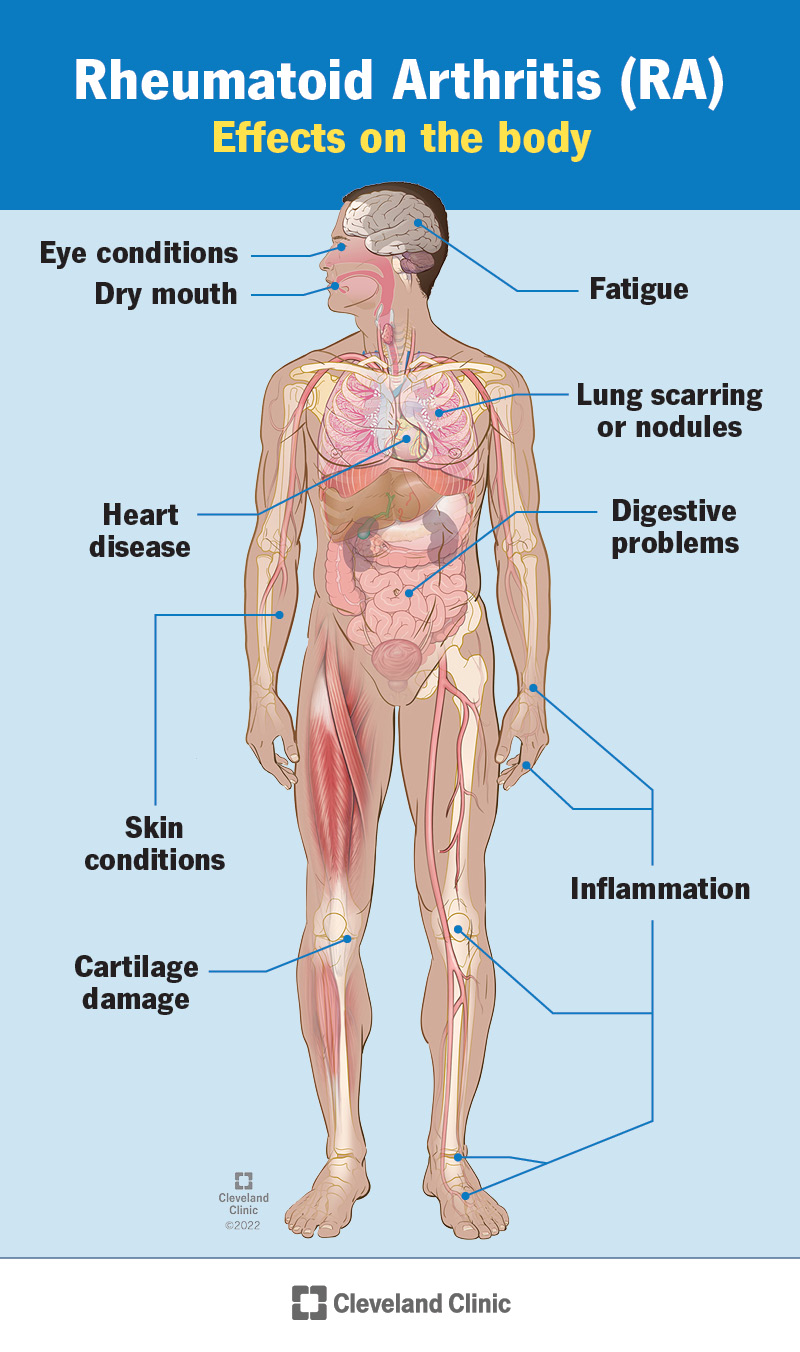

Extra-Articular Manifestations: A Gallery of Systemic Involvement

The term "extra-articular manifestations" (EAMs) serves as a broad umbrella for the diverse array of conditions that arise in RA outside of the musculoskeletal system. These EAMs are not mere complications; they are integral features of the disease, affecting approximately 40% of RA patients, often heralding a more severe disease course and contributing significantly to morbidity and mortality. They underscore the profound truth that RA is a disease of systemic inflammation, not just joint inflammation.

Let us now embark on a detailed exploration of how this systemic inflammation impacts specific organ systems, revealing the breadth and depth of RA’s reach.

The Cardiovascular System: A Silent Siege on the Heart and Vessels

Perhaps one of the most critical and often underestimated systemic impacts of RA is its profound effect on the cardiovascular system. Patients with RA have a significantly increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD), often comparable to that seen in type 2 diabetes, even after controlling for traditional risk factors like hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and obesity. This isn’t merely an association; it’s a direct consequence of chronic systemic inflammation.

Atherosclerosis, the hardening and narrowing of arteries, is accelerated in RA. The chronic inflammatory state directly promotes endothelial dysfunction – damage to the inner lining of blood vessels – and drives the formation and progression of atherosclerotic plaques. Inflammatory cytokines like TNF-alpha and IL-6 contribute to dyslipidemia (unhealthy cholesterol profiles) and insulin resistance, further fueling the atherosclerotic process. The plaques in RA patients tend to be more unstable and prone to rupture, increasing the risk of myocardial infarction (heart attack) and stroke.

Beyond atherosclerosis, RA can directly affect the heart itself:

- Pericarditis: Inflammation of the sac surrounding the heart (pericardium) can lead to chest pain and, in severe cases, pericardial effusion (fluid buildup) or even cardiac tamponade, a life-threatening compression of the heart.

- Myocarditis: Inflammation of the heart muscle (myocardium) is less common but can impair the heart’s pumping function, leading to heart failure.

- Valvular disease: While less frequent, chronic inflammation can sometimes lead to thickening and dysfunction of heart valves.

- Vasculitis: Though rare in its severe forms, rheumatoid vasculitis involves inflammation of blood vessel walls, potentially affecting small to medium-sized arteries throughout the body, including those supplying the heart, brain, or gastrointestinal tract, leading to organ damage, claudication, or even digital gangrene.

The cardiovascular implications of RA are a stark reminder that managing the disease effectively is not just about preserving joint function, but crucially about safeguarding life itself. Early and aggressive treatment to control systemic inflammation is paramount in mitigating these severe risks.

The Pulmonary System: Breath Held Captive

The lungs are another frequent target of RA’s systemic inflammation, often leading to chronic and debilitating conditions. Pulmonary manifestations can precede, coincide with, or follow the onset of joint symptoms, sometimes posing diagnostic challenges.

- Interstitial Lung Disease (ILD): This is arguably the most serious and common pulmonary complication. ILD in RA involves inflammation and fibrosis (scarring) of the lung tissue, specifically the interstitium – the tissue and space around the air sacs. Patients may experience progressive shortness of breath, a persistent dry cough, and fatigue. The most common patterns are usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) and non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP). RA-ILD can significantly impair lung function, leading to respiratory failure, and is a major cause of mortality in RA patients.

- Pleurisy/Pleural Effusion: Inflammation of the pleura (the membranes lining the lungs and chest cavity) can cause sharp chest pain, especially with breathing, and lead to fluid accumulation (effusion) around the lungs. While often asymptomatic, large effusions can cause shortness of breath.

- Rheumatoid Nodules: These firm lumps, characteristic of RA, can also form in the lungs. While often asymptomatic, they can cavitate, cause pneumothorax (collapsed lung), or be mistaken for lung cancer, necessitating careful evaluation.

- Bronchiolitis Obliterans: A rare but severe complication involving inflammation and scarring of the small airways, leading to progressive airflow obstruction and severe shortness of breath.

- Pulmonary Hypertension: Increased blood pressure in the arteries of the lungs, potentially stemming from chronic lung disease or vasculitis, can lead to right-sided heart failure.

The pulmonary involvement in RA underscores the need for vigilance, with clinicians often recommending baseline lung function tests and imaging for patients with suspected lung symptoms.

The Ocular System: Windows to Inflammation

The eyes, delicate and highly vascularized, offer another window into the systemic inflammation of RA. Ocular manifestations can range from mild irritation to severe vision-threatening conditions.

- Sjögren’s Syndrome (Secondary): A significant number of RA patients (10-15%) develop secondary Sjögren’s syndrome, an autoimmune condition primarily affecting moisture-producing glands. This leads to profound dry eyes (keratoconjunctivitis sicca), causing grittiness, burning, foreign body sensation, and increased risk of corneal damage and infection.

- Scleritis and Episcleritis: These conditions involve inflammation of the sclera (the white outer layer of the eye) and episclera (the tissue between the conjunctiva and the sclera), respectively. Episcleritis is generally milder, causing redness and discomfort. Scleritis, however, is more severe, causing intense pain, significant redness, and can lead to thinning or even perforation of the sclera, potentially causing vision loss. It is often a marker of more severe, systemic RA.

- Uveitis: Inflammation of the uvea (the middle layer of the eye, including the iris, ciliary body, and choroid) is less common in RA than in other forms of inflammatory arthritis but can cause pain, redness, light sensitivity, and blurred vision.

- Peripheral Ulcerative Keratitis: A rare but severe complication where the cornea (the clear front part of the eye) develops ulcers, potentially leading to perforation and vision loss.

Regular eye examinations, especially for those with symptoms of dry eyes or eye pain, are crucial for early detection and intervention.

The Hematologic System: Blood’s Battleground

The blood and blood-forming organs are also affected by the chronic inflammatory state of RA, leading to various hematologic abnormalities.

- Anemia of Chronic Disease (ACD): This is the most common hematologic manifestation, affecting up to 70% of RA patients. Chronic inflammation interferes with iron metabolism and red blood cell production, leading to a mild to moderate normocytic, normochromic anemia. Symptoms include fatigue, weakness, and reduced exercise tolerance.

- Felty’s Syndrome: A rare but severe triad characterized by RA, splenomegaly (enlarged spleen), and neutropenia (low neutrophil count). Patients with Felty’s syndrome are at a significantly increased risk of severe infections due to their compromised immune response.

- Thrombocytosis: An elevated platelet count can occur as an acute phase reactant in active RA, indicating ongoing inflammation. Conversely, some RA patients, particularly those with Felty’s syndrome, can develop thrombocytopenia (low platelet count).

- Lymphadenopathy: Enlarged lymph nodes can sometimes be observed, reflecting generalized immune system activation.

These hematologic changes underscore the systemic impact of RA on the bone marrow and immune cell production, contributing to the overall burden of the disease.

The Renal System: Kidneys Under Scrutiny

While the kidneys are not as commonly a direct target of RA inflammation as some other organs, they are not entirely immune, and certain complications can arise.

- Amyloidosis (AA Amyloidosis): This is a serious, albeit rare, complication where chronic inflammation leads to the deposition of abnormal protein fibrils (amyloid) in various organs, including the kidneys. These amyloid deposits can progressively impair kidney function, leading to proteinuria (protein in urine) and eventually renal failure.

- Glomerulonephritis: Direct inflammation of the kidney’s filtering units (glomeruli) is less common but can occur, sometimes in association with vasculitis.

- Drug-Induced Nephrotoxicity: Perhaps the most common renal issue in RA patients is kidney damage secondary to medications used to treat the disease, particularly non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and, less commonly, some disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) if not monitored carefully.

Regular monitoring of kidney function (serum creatinine, estimated glomerular filtration rate, urinalysis) is essential for all RA patients, particularly those on long-term medications.

The Neurological System: Nerves on Edge

The nervous system can be affected by RA in several ways, primarily through structural damage, direct inflammation, or compression.

- Cervical Myelopathy (Atlantoaxial Subluxation): Chronic inflammation in the cervical spine, particularly at the atlantoaxial joint (between the first two vertebrae), can lead to ligamentous laxity and joint destruction. This can result in subluxation (misalignment) of the vertebrae, potentially compressing the spinal cord. Symptoms can range from neck pain and stiffness to severe neurological deficits, including weakness, numbness, gait disturbance, and even paralysis. This is a surgical emergency.

- Entrapment Neuropathies: Joint inflammation and swelling can compress peripheral nerves. The most common example is carpal tunnel syndrome, where inflammation in the wrist compresses the median nerve, causing pain, numbness, and tingling in the hand and fingers. Tarsal tunnel syndrome can similarly affect the foot.

- Vasculitic Neuropathy: Inflammation of the small blood vessels supplying nerves can lead to nerve damage (neuropathy), resulting in pain, numbness, weakness, or foot drop. This is a manifestation of rheumatoid vasculitis.

- Mononeuritis Multiplex: A severe form of neuropathy where multiple individual nerves are affected in different parts of the body, often symmetrical.

These neurological complications highlight the potential for RA to impact not just mobility but also sensory and motor function, significantly affecting quality of life.

The Integumentary System: Skin’s Silent Signals

The skin, being the body’s largest organ, often reflects systemic inflammation through various manifestations.

- Rheumatoid Nodules: These subcutaneous nodules are the most common skin manifestation, occurring in about 20-30% of RA patients, typically over bony prominences (elbows, fingers, Achilles tendon) or pressure points. They are firm, non-tender, and range in size. While usually benign, they can ulcerate, become infected, or cause cosmetic concern. Less commonly, they can occur in internal organs (lungs, heart).

- Rheumatoid Vasculitis: As discussed, inflammation of blood vessels can manifest in the skin as purpura, ulcers, digital infarcts (tissue death in fingers/toes), or livedo reticularis (a mottled, purplish discoloration). Severe forms can lead to gangrene.

- Pyoderma Gangrenosum: A rare but severe ulcerative skin condition characterized by rapidly expanding, painful ulcers with violaceous borders. It is often associated with systemic inflammatory diseases, including RA.

- Palmar Erythema: Redness of the palms can sometimes be seen in active RA.

Skin manifestations can serve as visible indicators of disease activity and sometimes of more severe systemic involvement.

The Gastrointestinal System: A Complex Relationship

Direct RA involvement in the gastrointestinal tract is less common, but the GI system is significantly affected by RA in an indirect manner, primarily through the medications used for treatment.

- NSAID-Induced Gastropathy: Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are frequently used for pain and inflammation in RA but can cause significant gastrointestinal side effects, including gastritis, ulcers, and bleeding, potentially leading to perforation.

- Methotrexate-Induced Toxicity: Methotrexate, a cornerstone DMARD, can cause side effects like nausea, vomiting, oral ulcers (mucositis), and liver enzyme elevation.

- Biologic-Induced Effects: While generally well-tolerated, some biologics can increase the risk of infections, including gastrointestinal infections, or, in rare cases, trigger inflammatory bowel disease-like symptoms.

- Amyloidosis: As mentioned, amyloid deposition can affect the GI tract, leading to malabsorption, diarrhea, or constipation.

Managing GI side effects is a crucial aspect of RA care, often requiring prophylactic medications (e.g., proton pump inhibitors) and careful monitoring.

Metabolic and Endocrine Connections: The Wider Web

RA’s chronic inflammatory state extends its influence to metabolic and endocrine pathways, creating a wider web of systemic implications.

- Osteoporosis: RA patients are at a significantly increased risk of osteoporosis and fractures. This is multifactorial: chronic inflammation itself promotes bone resorption, reduced physical activity weakens bones, and corticosteroid use (a common RA treatment) is a major contributor to bone loss.

- Insulin Resistance and Type 2 Diabetes: Chronic systemic inflammation can contribute to insulin resistance, increasing the risk of developing type 2 diabetes. The inflammatory cytokines interfere with insulin signaling pathways.

- Body Composition Changes: Many RA patients experience "rheumatoid cachexia," characterized by a loss of lean muscle mass and an increase in fat mass, even if their overall weight remains stable. This contributes to weakness, fatigue, and metabolic dysfunction.

- Thyroid Dysfunction: There’s a higher prevalence of autoimmune thyroid diseases (e.g., Hashimoto’s thyroiditis) in RA patients, suggesting a shared autoimmune predisposition.

These metabolic and endocrine effects highlight the pervasive nature of RA, influencing the body’s fundamental physiological processes.

Psychological and Social Dimensions: The Invisible Burden

While not an organ system in the traditional sense, the mind and an individual’s social well-being are profoundly impacted by RA’s systemic nature, constituting an invisible but immensely heavy burden. Chronic pain, debilitating fatigue (often driven by systemic inflammation), and functional limitations take a significant toll on mental health.

- Depression and Anxiety: These are highly prevalent in RA patients, often two to three times higher than in the general population. The relentless pain, unpredictable flares, loss of independence, and uncertainty about the future can lead to feelings of hopelessness, despair, and anxiety. Systemic inflammation itself can also influence neurobiology and contribute to mood disorders.

- Fatigue: Beyond mere tiredness, RA fatigue is a profound, pervasive exhaustion that is often disproportionate to disease activity. It significantly impacts daily life, work, and social interactions, and is driven by inflammatory cytokines and chronic pain.

- Sleep Disturbances: Pain, discomfort, and inflammation often disrupt sleep patterns, creating a vicious cycle where poor sleep exacerbates pain and fatigue.

- Social Isolation and Quality of Life: The physical limitations and invisible symptoms can lead to withdrawal from social activities, loss of employment, and a significant reduction in overall quality of life. The psychological burden can be as debilitating as the physical symptoms, if not more so.

Addressing these psychological and social dimensions is an integral part of comprehensive RA care, requiring a multidisciplinary approach involving mental health professionals, occupational therapists, and social workers.

The Evolution of Understanding and Treatment: From Palliation to Precision

The journey of understanding RA’s systemic nature has paralleled the evolution of its treatment. Historically, RA management was largely palliative, focusing on pain relief and managing symptoms as they arose. The advent of disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) like methotrexate in the 1980s marked a turning point, offering the ability to slow disease progression. However, the true revolution came with the development of biologic DMARDs and targeted synthetic DMARDs (tsDMARDs) in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

These therapies, which specifically target key inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-alpha inhibitors, IL-6 inhibitors) or immune cells (e.g., B-cell depletion), have transformed the landscape of RA care. By precisely modulating the immune response, they not only reduce joint inflammation and prevent joint damage but also significantly mitigate the risk and severity of extra-articular manifestations.

The current paradigm emphasizes:

- Early Diagnosis: Recognizing RA promptly is crucial, as early intervention can prevent irreversible joint damage and systemic complications.

- Treat-to-Target Strategy: This involves setting a specific treatment goal (e.g., remission or low disease activity) and regularly adjusting therapy to achieve and maintain that target.

- Multidisciplinary Care: Recognizing RA’s systemic reach necessitates a team approach involving rheumatologists, cardiologists, pulmonologists, ophthalmologists, physical and occupational therapists, mental health professionals, and dietitians.

This shift in understanding and treatment has moved RA from a relentlessly progressive, debilitating disease to one where remission or low disease activity is an achievable goal for many, significantly improving long-term outcomes and reducing systemic damage.

Living Beyond the Joints: A Holistic Approach

For individuals living with RA, understanding its systemic nature is not just academic; it’s empowering. It transforms the perception of the disease from a localized battle to a comprehensive war, necessitating a holistic and proactive approach to health.

- Patient Education and Empowerment: Knowledge about EAMs allows patients to be vigilant for symptoms beyond joint pain, prompting earlier discussion with their healthcare team.

- Adherence to Treatment: Consistent use of prescribed DMARDs and biologics is paramount, not just for joint health but for systemic protection.

- Lifestyle Modifications:

- Regular Exercise: Tailored physical activity helps maintain joint function, muscle strength, and cardiovascular health, while also combating fatigue and improving mood.

- Balanced Diet: An anti-inflammatory diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and omega-3 fatty acids can support overall health and potentially mitigate inflammation.

- Smoking Cessation: Smoking is a major risk factor for developing RA, increases disease severity, and significantly exacerbates pulmonary and cardiovascular complications.

- Stress Management: Techniques like mindfulness, meditation, and yoga can help manage the psychological burden of chronic illness.

- Proactive Screening: Regular monitoring for EAMs (e.g., cardiovascular risk assessment, lung function tests, eye exams) is crucial for early detection and intervention.

- Mental Health Support: Acknowledging and addressing the psychological toll through therapy, support groups, or medication is as important as managing physical symptoms.

The Horizon: Future Directions and Unanswered Questions

Despite monumental strides, the story of RA and its systemic impact continues to unfold. Research is relentlessly pushing boundaries, seeking even deeper understanding and more precise interventions.

- Personalized Medicine: Identifying biomarkers that predict individual disease course, response to specific therapies, and risk of particular EAMs holds the promise of truly personalized RA management.

- Novel Therapeutic Targets: Ongoing research into new inflammatory pathways and cellular interactions continues to yield potential new drug targets, offering hope for patients who don’t respond to current treatments.

- Prevention: Understanding the earliest triggers and risk factors for RA is crucial for developing strategies to prevent its onset, especially in individuals at high genetic risk.

- Regenerative Medicine: While still in nascent stages, approaches like stem cell therapy could potentially repair damaged tissues in joints and other organs affected by chronic inflammation.

- Addressing the Unmet Needs: Persistent challenges include managing fatigue, pain, and the psychological burden, even in patients with well-controlled joint disease.

Conclusion: A Symphony of Understanding and Hope

The journey through the landscape of rheumatoid arthritis beyond the joints reveals a profound and complex truth: this is a systemic disease, a testament to the intricate interconnectedness of the human body. The initial image of gnarled hands gives way to a panoramic view of potential assaults on the heart, lungs, eyes, blood, and even the very fabric of mental well-being.

This comprehensive understanding is not meant to instill fear, but rather to empower. It underscores the remarkable progress made in diagnosis and treatment, transforming RA from a relentless destroyer into a manageable chronic condition for many. It highlights the critical importance of a vigilant, holistic approach, where patients and their healthcare teams work in concert to not only preserve joint function but to safeguard the health and integrity of the entire body.

The story of RA is one of ongoing discovery, resilience, and hope. As scientific understanding deepens and therapeutic options expand, the narrative shifts from one of inevitable decline to one of proactive management, allowing individuals with RA to live full, productive lives, "beyond the joints" in every sense of the phrase.