The Spacing Solution: How to Master Zinc for Optimal Absorption and Interaction Avoidance

In the grand symphony of human health, where countless nutrients, enzymes, and compounds play their vital roles, zinc often finds itself as a crucial yet temperamental soloist. It is an unsung hero, participating in over 300 enzymatic reactions, fortifying our immune system, orchestrating DNA synthesis, and even shaping our senses of taste and smell. Its absence can lead to a cascade of health issues, from compromised immunity and delayed wound healing to neurological dysfunction and impaired growth. Yet, for all its undeniable power, zinc is surprisingly delicate, a mineral whose efficacy hinges not just on its presence, but on its precise timing and context.

This is the story of "The Spacing Solution" – a strategic approach to taking zinc that transforms a potentially fragile supplement into a robust ally. It’s a narrative born from scientific understanding, driven by the desire to maximize health benefits, and essential for anyone seeking to harness zinc’s full potential while deftly navigating the minefield of absorption inhibitors and drug interactions. For the knowledgeable individual, understanding these nuances isn’t just a matter of compliance; it’s an act of empowerment, a conscious decision to optimize one’s physiological landscape.

The Unsung Hero: Why Zinc Commands Our Attention

Before we delve into the intricacies of its absorption and interaction, it’s paramount to truly appreciate zinc’s profound significance. Imagine a bustling metropolis where zinc acts as a master architect, a diligent builder, and a vigilant peacekeeper all at once.

- Immune System Fortification: Zinc is perhaps best known for its role in immunity. It’s critical for the development and function of immune cells, including T-lymphocytes and natural killer cells. A zinc deficiency can cripple the immune response, making the body vulnerable to infections and prolonging recovery times. It influences cytokine production and acts as an antioxidant, protecting immune cells from oxidative damage during inflammation.

- Enzymatic Maestro: As a cofactor for over 300 enzymes, zinc is involved in virtually every major metabolic pathway. From energy production to protein synthesis, from nucleic acid metabolism to carbohydrate utilization, zinc ensures that the body’s biochemical machinery runs smoothly and efficiently.

- Cellular Growth and Repair: Zinc is indispensable for cell division, growth, and tissue repair. This makes it vital for wound healing, skin health, and the healthy development of children and adolescents. It’s a key player in maintaining the integrity of the skin and mucosal barriers.

- Antioxidant Defender: Zinc is a component of superoxide dismutase (SOD), a powerful antioxidant enzyme that protects cells from damaging free radicals. This protective role extends to mitigating oxidative stress throughout the body, which is implicated in aging and various chronic diseases.

- Sensory Perception: Our ability to taste and smell relies heavily on zinc. It’s involved in the formation of gustin, a protein essential for taste bud function, and a deficiency can lead to altered or diminished senses.

- Hormonal Balance: Zinc plays a role in regulating various hormones, including insulin, thyroid hormones, and sex hormones. It is particularly important for male reproductive health, influencing testosterone production and sperm quality.

- Neurological Function: Emerging research highlights zinc’s role in neurotransmission, brain development, and cognitive function. It impacts memory, learning, and mood regulation, underscoring its broad influence on mental well-being.

Given this extensive portfolio of responsibilities, it becomes clear that maintaining optimal zinc levels is not merely beneficial, but foundational to robust health. Yet, despite its importance, zinc deficiency is remarkably common globally, often due to inadequate dietary intake or, as we shall explore, impaired absorption.

The Battleground: Understanding Zinc Absorption

The journey of zinc from a supplement or food item to its active role within our cells is fraught with potential obstacles. The human digestive tract, while a marvel of efficiency, is also a highly competitive environment. Zinc, like a shy but essential guest, must navigate this crowded space, vying for attention and passage.

1. The Gut’s Gatekeepers: A Molecular Overview

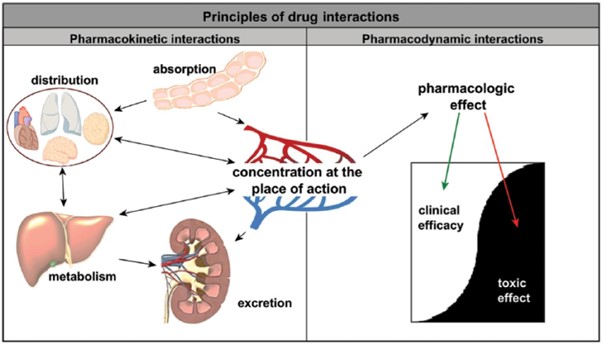

Upon ingestion, zinc ions are released from their dietary or supplemental forms in the stomach, primarily due to the acidic environment. They then move into the small intestine, where the majority of absorption occurs. This process is not passive; it involves specific transport proteins on the brush border of intestinal cells (enterocytes). Key players include the ZIP (Zrt- and Irt-like Protein) transporters, particularly ZIP4, which facilitate zinc uptake into the cell, and ZnT (Zinc Transporter) proteins, like ZnT1, which help move zinc out of the enterocyte into the bloodstream. The efficiency of these transporters, along with the solubility of zinc, dictates how much actually makes it into systemic circulation.

2. Intrinsic Absorption Blockers: The Dietary Antinutrients

Certain compounds naturally present in foods act as "molecular handcuffs," binding to zinc and preventing its absorption. These are the primary culprits when zinc is taken alongside or too close to meals.

- Phytates (Phytic Acid): Found abundantly in grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds, phytates are phosphorus compounds that bind strongly to essential minerals like zinc, iron, and calcium. This binding forms insoluble complexes, rendering the minerals unavailable for absorption. Think of phytates as molecular "velcro" that latches onto zinc, preventing it from passing through the intestinal wall. The higher the phytate content of a meal, the lower the zinc absorption.

- Example: A zinc supplement taken with a bowl of oatmeal or a bean-heavy chili will have significantly reduced bioavailability.

- Oxalates: Present in foods like spinach, rhubarb, beet greens, and cocoa, oxalates can also bind to minerals, though their impact on zinc is generally less pronounced than phytates.

- Tannins: Found in tea, coffee, red wine, and some fruits, tannins are polyphenolic compounds that can complex with minerals, inhibiting their absorption.

- Example: Drinking black tea immediately after taking zinc can lessen its uptake.

- Dietary Fiber: While essential for gut health, very high levels of insoluble fiber can, to some extent, physically entrap minerals and reduce their contact with absorption sites, though this is less of a concern than phytates.

3. The Mineral Melee: Competitive Absorption

The gut is not just battling antinutrients; it’s also a stage for a fierce competition among minerals for shared transporters. Imagine several people trying to get through a single door at the same time.

- Iron: Perhaps the most significant competitor. Iron and zinc often utilize the same transport pathways, such as the divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1). High doses of one can significantly impair the absorption of the other. This is a critical consideration for individuals supplementing with both minerals, especially pregnant women or those with anemia.

- Practical implication: Taking a high-dose iron supplement concurrently with zinc is a recipe for reduced efficacy of both.

- Copper: Zinc and copper have a fascinating, often antagonistic, relationship. While both are essential, high zinc intake can induce a copper deficiency by stimulating the production of metallothionein in intestinal cells, which preferentially binds to copper and prevents its absorption. Conversely, very high copper intake can sometimes interfere with zinc.

- Calcium: Large doses of calcium, especially from supplements, can also interfere with zinc absorption, particularly when zinc intake is already marginal. This interaction is less potent than iron but still relevant in multi-mineral formulations.

- Magnesium: While generally less competitive than iron or calcium, extremely high doses of magnesium might theoretically compete for some absorption pathways.

The takeaway from understanding these absorption challenges is clear: the presence of food, certain plant compounds, and other minerals can drastically reduce the amount of zinc that actually reaches your bloodstream, rendering your efforts to supplement less effective.

The Unseen Saboteurs: Drug Interactions

Beyond dietary factors, zinc’s journey can be further complicated by prescription and over-the-counter medications. These interactions are often more insidious, as they can lead not only to reduced zinc efficacy but also to impaired drug action or even nutrient depletion over time.

1. Chelation Station: Drugs That Bind Zinc

Certain medications are designed to bind to metal ions, a process known as chelation. While sometimes therapeutic (e.g., for heavy metal toxicity), this can be detrimental when it involves essential minerals like zinc.

- Antibiotics (Tetracyclines & Quinolones): This is one of the most well-documented and clinically significant interactions.

- Mechanism: Antibiotics like tetracycline, doxycycline, ciprofloxacin, and levofloxacin form insoluble chelates with polyvalent metal ions such as zinc, calcium, iron, and magnesium in the gastrointestinal tract. This binding prevents both the antibiotic and the mineral from being absorbed effectively.

- Consequence: Reduced antibiotic efficacy (leading to treatment failure) and reduced zinc absorption.

- Example: Taking a zinc supplement within hours of an antibiotic dose could render the antibiotic less effective against an infection.

- Bisphosphonates: Used to treat osteoporosis (e.g., alendronate, risedronate).

- Mechanism: These drugs can also chelate with divalent cations, including zinc, potentially reducing the absorption of both.

- Consequence: Reduced bisphosphonate efficacy and zinc absorption.

- Penicillamine: A chelating agent used to treat Wilson’s disease (copper overload) and rheumatoid arthritis.

- Mechanism: While its primary target is copper, penicillamine is a potent chelator of other metals, including zinc.

- Consequence: Long-term use of penicillamine can lead to significant zinc depletion, necessitating careful monitoring and supplementation.

2. pH Alterations: The Stomach Acid Story

The acidity of the stomach plays a crucial role in mineral absorption, as it helps dissociate minerals from their food matrix and keeps them soluble. Medications that alter stomach pH can thus impact zinc.

- Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs) & H2 Blockers: Medications like omeprazole, lansoprazole (PPIs), and ranitidine, famotidine (H2 blockers) are widely used to reduce stomach acid production.

- Mechanism: By raising gastric pH, these drugs can impair the solubility of zinc, making it less available for absorption in the small intestine. Zinc needs an acidic environment to become properly ionized for uptake.

- Consequence: Chronic use of acid-reducing medications can contribute to zinc deficiency over time, even with adequate dietary intake.

3. Diuretic Depletion: Flushing Out Minerals

Some medications increase the excretion of minerals through the kidneys.

- Thiazide and Loop Diuretics: Commonly prescribed for high blood pressure and fluid retention (e.g., hydrochlorothiazide, furosemide).

- Mechanism: These diuretics increase urinary excretion of various electrolytes, including zinc.

- Consequence: Long-term use can lead to increased zinc losses and potential deficiency, requiring proactive management.

4. Other Notable Interactions

- NSAIDs (Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs): While not a direct chelation or pH interaction, chronic NSAID use can lead to gastrointestinal irritation and bleeding, which can indirectly affect nutrient absorption and potentially increase nutrient losses.

- Corticosteroids: Long-term use of corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone) can increase zinc excretion and interfere with its metabolism.

These interactions underscore a critical point: zinc’s journey through the body is not isolated. It is intricately woven into the complex tapestry of our internal chemistry, where medications, even those for seemingly unrelated conditions, can have profound effects.

The Spacing Solution: A Strategy for Success

Understanding the myriad ways zinc absorption can be hindered and its efficacy compromised is the first step. The second, and perhaps most empowering, step is to implement "The Spacing Solution." This is not just a haphazard approach; it’s a calculated, scientifically informed strategy designed to create an optimal window for zinc’s absorption, minimizing interference from food, other minerals, and medications.

1. The Core Principle: Creating an "Empty Room"

At its heart, The Spacing Solution is about giving zinc its own dedicated "space" in the digestive tract. Imagine zinc as an important guest arriving at a busy airport. If it arrives during rush hour, it gets stuck in traffic, waits in long lines, and might miss its connecting flight. If it arrives during a quiet period, it moves swiftly and efficiently to its destination. Our goal is to create that quiet period.

2. Timing is Everything: Practical Application

The ideal timing for zinc supplementation depends heavily on what you are trying to avoid interacting with.

-

General Rule: On an Empty Stomach (with a caveat):

- For maximum absorption, zinc is generally best taken on an empty stomach (at least 1 hour before or 2 hours after a meal). This minimizes interaction with phytates, oxalates, tannins, and other minerals in food.

- The Caveat: Zinc, especially in higher doses or certain forms (like zinc sulfate), can cause gastrointestinal upset, nausea, or stomach cramps when taken on an entirely empty stomach. If this occurs, it’s better to take it with a small, low-phytate meal.

-

Strategic Pairing with Food (if GI upset is an issue):

- If you experience GI discomfort on an empty stomach, opt for a small meal that is low in phytates and fiber. Examples include a piece of fruit (like an apple or banana), a small portion of lean protein, or a few crackers (if not whole-grain). Avoid nuts, seeds, legumes, and large amounts of whole grains.

- The goal here is to buffer the stomach without introducing significant absorption inhibitors.

-

Separation from Dietary Antinutrients and Other Minerals:

- Rule: If taking zinc for therapeutic purposes and wanting to maximize absorption, separate it from meals rich in phytates (grains, legumes, nuts), high-fiber foods, tea, coffee, and other mineral supplements (especially iron, copper, calcium) by at least 2-4 hours.

- Example: If you have a fiber-rich breakfast, take your zinc mid-morning. If you take an iron supplement in the evening, take zinc earlier in the afternoon.

-

Crucial Separation from Medications:

- This is arguably the most critical aspect of the Spacing Solution, as interactions can compromise both drug efficacy and zinc absorption.

- Antibiotics (Tetracyclines & Quinolones): Separate zinc by the widest possible margin. Aim for at least 2-4 hours before or 4-6 hours after the antibiotic dose. Some sources recommend an even longer interval (e.g., 6 hours) due to the strong chelation effect. Always consult your pharmacist or doctor for specific advice on your antibiotic.

- Bisphosphonates: Similar to antibiotics, aim for at least 2-4 hours before or after taking bisphosphonates. These drugs often have very specific timing instructions themselves (e.g., first thing in the morning with water, 30-60 minutes before food), so zinc timing must fit around them.

- Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs) & H2 Blockers: While spacing won’t entirely counteract the pH effect, taking zinc when stomach acid is most likely to be present might offer a slight advantage. Consider taking zinc before a meal if you take your PPI at a different time, or discuss with your doctor whether a different zinc form might be more suitable. However, for chronic PPI users, the underlying issue of reduced acid remains, and supplementation needs to be carefully considered.

- Diuretics: Spacing here is less about direct interaction and more about consistent intake. If on diuretics, ensure regular zinc intake and consider discussing potential deficiency with your doctor, who might recommend monitoring or specific supplementation.

- Penicillamine: Due to its strong chelating properties, zinc supplementation in individuals taking penicillamine should be carefully managed by a healthcare professional to avoid both zinc deficiency and interference with the drug’s action.

3. Choosing the Right Form of Zinc: Bioavailability Matters

Not all zinc supplements are created equal. The form of zinc affects its solubility, absorption, and potential for GI upset. For a knowledgeable audience, understanding these differences is key.

- Zinc Gluconate/Acetate: Common, readily available, and generally well-absorbed. Often used in lozenges for cold duration reduction. Can cause GI upset in higher doses on an empty stomach.

- Zinc Citrate: Also well-absorbed and generally well-tolerated. Often considered a good balance between efficacy and GI comfort.

- Zinc Picolinate: Zinc bound to picolinic acid, a natural chelator. Some studies suggest superior absorption, while others show no significant difference from other forms. Generally well-tolerated.

- Zinc Sulfate: Historically used, but tends to cause more GI irritation (nausea, stomach upset) due to its high zinc content and acidity. Often taken with food for this reason, which can compromise absorption. Less commonly recommended now for general supplementation.

- Zinc L-Carnosine: A chelated compound often used for gut health (e.g., leaky gut, ulcers). It releases zinc slowly and locally in the stomach, potentially reducing systemic absorption initially but offering targeted benefits. Generally well-tolerated.

For most individuals, zinc gluconate, citrate, or picolinate are excellent choices, offering good bioavailability with a reasonable side-effect profile, especially when implementing the Spacing Solution.

Beyond Timing: Holistic Strategies for Optimal Zinc Status

While The Spacing Solution focuses on optimizing absorption from supplements, a comprehensive approach to zinc status also includes dietary and lifestyle considerations.

- Dietary Sources: Prioritize zinc-rich foods.

- High: Oysters are an exceptional source. Red meat (beef, lamb, pork), poultry (chicken, turkey), and crab are also excellent.

- Moderate: Legumes (chickpeas, lentils, beans), nuts (cashews, almonds), seeds (pumpkin, sesame), dairy products (milk, cheese), eggs, and whole grains.

- Note: Plant-based sources contain phytates, so soaking, sprouting, and fermenting grains and legumes can improve zinc bioavailability.

- Gut Health: A healthy gut microbiome and intact intestinal lining are crucial for efficient nutrient absorption. Conditions like inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), celiac disease, or chronic diarrhea can impair zinc absorption. Addressing underlying gut issues can significantly improve zinc status.

- Monitoring: For those at risk of deficiency or on long-term medications, blood tests can assess zinc levels. However, serum zinc levels don’t always accurately reflect intracellular zinc status, so interpretation requires clinical expertise.

- Dosage Considerations: Adhere to recommended daily allowances (RDA) for maintenance (e.g., 8-11 mg/day for adults). Therapeutic doses (e.g., 15-50 mg/day for short periods) should be used under medical supervision, as excessive zinc intake can lead to copper deficiency and other adverse effects.

Navigating the Nuances: When to Seek Professional Guidance

While the Spacing Solution empowers individuals to take control of their zinc supplementation, certain situations warrant professional medical advice.

- High-Dose Supplementation: If considering zinc doses significantly above the RDA, especially for extended periods, consult a doctor or registered dietitian. High zinc intake can lead to copper deficiency, impaired immune function, and other adverse effects.

- Chronic Medication Use: If you are on multiple prescription medications, particularly those known to interact with zinc (antibiotics, PPIs, diuretics, bisphosphonates), discuss your zinc supplementation plan with your doctor and pharmacist. They can help identify potential interactions and adjust timing or dosage accordingly.

- Underlying Health Conditions: Individuals with malabsorption syndromes, kidney disease, liver disease, or other chronic illnesses should always consult a healthcare provider before starting zinc supplementation.

- Symptoms of Deficiency or Toxicity: If you suspect zinc deficiency (e.g., frequent infections, slow wound healing, hair loss, taste/smell changes) or zinc toxicity (e.g., nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, metallic taste), seek medical attention.

Conclusion: The Art of Precision

The story of zinc is a compelling reminder that in the intricate world of human physiology, few things operate in isolation. Zinc, the quiet yet powerful orchestrator of countless bodily functions, demands our respect and understanding. Its potential to enhance immunity, fuel cellular repair, and fortify our overall well-being is undeniable, yet its journey from supplement to cellular action is a delicate dance, easily disrupted by the crowded stage of our digestive system.

"The Spacing Solution" is more than just a set of rules; it’s an art of precision, a commitment to mindful supplementation. By strategically timing zinc intake – creating that "empty room" for its absorption, separating it from dietary antagonists, and meticulously avoiding drug interactions – we transform a potential health gamble into a calculated success. For the knowledgeable individual, this approach is an act of informed self-care, ensuring that this essential mineral can truly fulfill its destiny as a cornerstone of vibrant health. With a little planning and a lot of understanding, zinc can indeed become the powerful ally it was always meant to be.