Ginger and Nausea: An Age-Old Remedy That Still Works – A Timeless Narrative of Healing

In the grand tapestry of human history, where the ceaseless search for comfort and relief has driven countless explorations, certain remedies emerge from the mists of time with an almost mythical resilience. They whisper across generations, their efficacy proven not just by empirical observation, but by the very persistence of their use. Among these venerable healers, one root stands out, its gnarled, aromatic presence a beacon of hope against one of the body’s most universally unpleasant sensations: nausea. This is the story of ginger, Zingiber officinale, a spice and a medicine whose age-old wisdom continues to resonate with undeniable power in the modern world.

The experience of nausea is as ancient as humanity itself. From the queasy discomfort of early pregnancy to the debilitating sickness of a voyage across tempestuous seas, from the stomach-churning aftermath of a questionable meal to the profound distress induced by illness or potent medicines, the human body has always sought solace from this pervasive malady. And for millennia, across continents and cultures, the fiery embrace of ginger has offered a reliable, gentle, yet profoundly effective antidote. It’s a narrative not just of botanical chemistry, but of cultural exchange, scientific discovery, and the enduring power of nature’s pharmacy.

A Journey Through Time: Ginger’s Historical Tapestry

Our story begins in the verdant, tropical climes of Southeast Asia, specifically the Indian subcontinent and China, where ginger is believed to have originated. Here, its distinctive aroma and pungent flavor were first appreciated, not merely as a culinary delight, but as a potent medicinal agent. Its cultivation dates back over 5,000 years, making it one of the earliest domesticated spices and herbs.

Ancient Origins and Traditional Wisdom:

In Ayurveda, the ancient Indian system of medicine, ginger is revered as a "universal great medicine" (vishwabhesaj). It’s lauded for its ability to balance the body’s doshas (Vata, Pitta, Kapha), particularly beneficial for digestion and alleviating various ailments. Ayurvedic texts describe ginger’s warming properties, its capacity to ignite agni (digestive fire), and its efficacy in dispelling ama (toxins) – all concepts intrinsically linked to digestive health and the prevention of nausea. Dried ginger, known as shunthi, was considered particularly potent for its anti-emetic effects.

Similarly, in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), ginger (Sheng Jiang for fresh, Gan Jiang for dried) holds a pivotal position. It’s categorized as a warming herb, vital for dispelling cold, promoting circulation, and harmonizing the stomach. TCM practitioners used ginger extensively to treat stomach upset, morning sickness, motion sickness, and to counteract the "cold" properties of other herbs. Its ability to "descend rebellious qi" (a concept referring to stomach energy flowing upwards, causing nausea and vomiting) was a cornerstone of its application.

Global Spread and Classical Adoption:

From its Asian cradle, ginger embarked on an extraordinary journey, carried by traders and explorers along ancient spice routes. By the 1st century AD, it had reached the Mediterranean, becoming a prized commodity in the Roman Empire. Dioscorides, the renowned Greek physician and pharmacologist, documented its medicinal uses, including its benefits for the stomach and its warming properties. Galen, another influential Roman physician, also noted its digestive virtues. It was not merely a luxury item for the wealthy; its therapeutic value was recognized and utilized.

During the Islamic Golden Age, scholars and physicians like Avicenna (Ibn Sina) further elaborated on ginger’s medicinal properties in their comprehensive medical texts, contributing to its sustained use across the Middle East and North Africa. By the Middle Ages, ginger was firmly entrenched in European pharmacopoeias, valued for its ability to warm the body, aid digestion, and combat nausea – a particularly welcome remedy during long sea voyages and periods of widespread illness. Its presence was so ubiquitous that it even became a common ingredient in gingerbread, a culinary tradition that persists to this day, subtly linking us to its ancient past.

Folklore and Enduring Appeal:

Across centuries and continents, ginger wasn’t just confined to the formal medical texts of scholars. It permeated folk medicine, becoming a staple in grandmothers’ remedies and household cures. A slice of fresh ginger steeped in hot water for an upset stomach, a ginger chew for motion sickness, or candied ginger for morning sickness – these practices were passed down, generation to generation, embodying an empirical wisdom refined over countless personal experiences.

The enduring appeal of ginger lies precisely in this dual heritage: its deep roots in ancient, sophisticated medical systems and its widespread adoption as a trusted, accessible home remedy. While many other traditional cures faded into obscurity, ginger persisted, a testament to its consistent, reliable efficacy. Its story is one of unwavering utility, a natural healer that has weathered the storms of time, awaiting the spotlight of modern scientific validation.

The Nausea Enigma: Understanding the Body’s Distress Signal

Before delving into how ginger works its magic, it’s essential to understand the complex phenomenon of nausea itself. It is not merely a feeling of sickness; it is a sophisticated, protective mechanism orchestrated by the body, designed to alert us to potential harm and, if necessary, to expel noxious substances. Yet, its triggers are manifold, and its experience profoundly unpleasant, often debilitating.

What is Nausea?

Nausea is defined as an unpleasant, wave-like sensation in the back of the throat and stomach, sometimes accompanied by an urge to vomit. It’s a subjective experience, varying in intensity, but always signaling distress within the gastrointestinal system or the central nervous system. Vomiting (emesis) is the forceful expulsion of stomach contents and is often, though not always, preceded by nausea.

The Physiology of Nausea and Vomiting:

The process is an intricate dance involving multiple pathways in the brain and body:

- The Chemoreceptor Trigger Zone (CTZ): Located outside the blood-brain barrier in the area postrema, the CTZ is a crucial hub. It acts as a surveillance system, highly sensitive to chemical toxins in the blood and cerebrospinal fluid. When activated (e.g., by chemotherapy drugs, toxins, or metabolic disturbances), it signals the vomiting center.

- The Vomiting Center: This is not a single anatomical structure but a functional area in the brainstem (specifically, the nucleus tractus solitarius – NTS) that integrates various sensory inputs.

- Peripheral Inputs:

- Gastrointestinal Tract: Irritation, distension, or inflammation of the stomach and intestines (e.g., from food poisoning, gastroenteritis, or overeating) activate vagal and sympathetic afferent nerves. These nerves carry signals to the NTS.

- Vestibular System: The inner ear’s balance system, when overstimulated (e.g., by motion sickness), sends signals to the vomiting center via the cerebellum.

- Higher Cortical Centers: Emotional states (anxiety, fear), unpleasant sights or smells, and even anticipation (e.g., anticipatory nausea before chemotherapy) can directly stimulate the vomiting center.

- Neurotransmitter Symphony: The communication within these pathways relies on various neurotransmitters:

- Serotonin (5-HT): Particularly 5-HT3 receptors, are heavily involved in nausea triggered by GI irritation and chemotherapy.

- Dopamine: D2 receptors in the CTZ play a significant role.

- Histamine: H1 receptors, particularly in motion sickness.

- Acetylcholine: Muscarinic (M1) receptors, also involved in motion sickness.

- Substance P: Neurokinin-1 (NK1) receptors are important, especially in delayed chemotherapy-induced nausea.

Common Causes of Nausea:

The triggers are diverse, highlighting the broad utility of an effective anti-emetic:

- Motion Sickness: Discrepancy between visual and vestibular input.

- Morning Sickness (Pregnancy-Related Nausea and Vomiting): Hormonal changes, particularly elevated hCG and estrogen.

- Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting (CINV): Direct cytotoxic effects on the GI tract and CTZ.

- Post-Operative Nausea and Vomiting (PONV): Anesthesia, pain medication, surgical stress.

- Gastrointestinal Upset: Food poisoning, viral gastroenteritis, acid reflux, ulcers.

- Migraines: Neurological mechanisms.

- Medication Side Effects: Many drugs can induce nausea.

- Anxiety and Stress: Psychological factors.

Given the widespread prevalence and varied etiologies of nausea, the need for safe, effective, and readily available remedies is paramount. This is precisely where ginger, with its multi-faceted approach, steps onto the modern stage.

Unveiling the Mechanisms: How Ginger Works Its Magic

For centuries, ginger’s anti-nausea effects were understood through observation. Now, modern science is meticulously unraveling the complex biochemistry behind this ancient wisdom, revealing a sophisticated interplay of compounds that target multiple pathways involved in nausea and vomiting.

The Bioactive Arsenal:

The primary active compounds responsible for ginger’s medicinal properties are found in its oleoresin – the oily resin that gives ginger its characteristic pungency. These include:

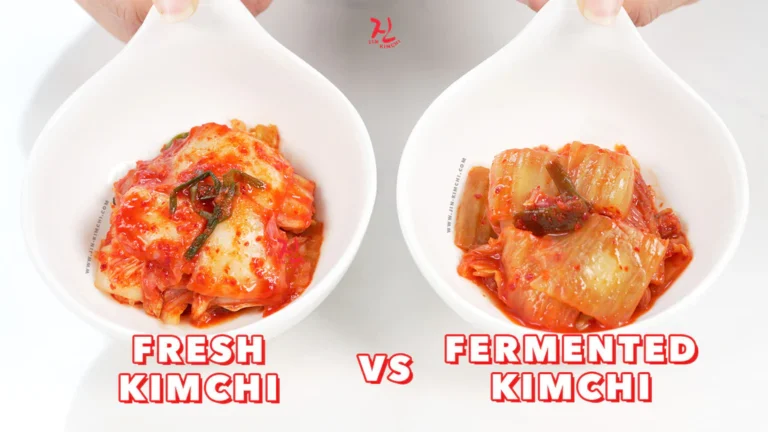

- Gingerols: The most abundant and well-studied compounds in fresh ginger, particularly 6-gingerol, 8-gingerol, and 10-gingerol. These are powerful antioxidants and anti-inflammatory agents.

- Shogaols: When ginger is dried or cooked, gingerols undergo a dehydration reaction, converting into shogaols (e.g., 6-shogaol, 8-shogaol, 10-shogaol). These compounds are often more pungent and are thought to have even stronger anti-emetic and anti-inflammatory properties than gingerols. This transformation explains why dried ginger powder can sometimes feel more potent.

- Zingerone: A less pungent compound, formed when gingerols are cooked or stored for extended periods. It contributes to the sweet-spicy aroma.

- Volatile Oils: A complex mixture of compounds like zingiberene, which contribute to ginger’s distinctive aroma but also possess some therapeutic effects.

A Multi-Targeted Approach:

Unlike many conventional anti-emetic drugs that often target a single neurotransmitter pathway, ginger appears to exert its effects through a more holistic, multi-pronged strategy, which likely contributes to its broad efficacy and relatively low side-effect profile.

-

Serotonin (5-HT3) Receptor Antagonism: This is one of the most significant proposed mechanisms. Many anti-emetic drugs (like ondansetron) work by blocking 5-HT3 receptors. Research suggests that gingerols and shogaols can act as antagonists at these receptors, both in the gut (where serotonin release can trigger vagal afferent signals) and in the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ). By blocking serotonin’s action, ginger helps to interrupt the nausea signal before it reaches the brain’s vomiting center. This mechanism is particularly relevant for chemotherapy-induced nausea and gastrointestinal upsets.

-

Enhanced Gastric Motility: Nausea is often associated with delayed gastric emptying and gastric stasis. Ginger has been shown to stimulate gastric emptying and increase the tone and motility of the gastrointestinal tract. By moving stomach contents into the small intestine more efficiently, ginger can reduce stomach distension and the feeling of fullness and discomfort that often precedes nausea. This effect is thought to be mediated through its action on cholinergic M3 receptors and possibly direct stimulation of smooth muscle.

-

Anti-inflammatory Effects: Inflammation in the gut can contribute significantly to nausea and discomfort. Gingerols and shogaols are potent anti-inflammatory compounds, capable of inhibiting the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and enzymes like COX-2 (cyclooxygenase-2), similar to NSAIDs but through different mechanisms. By reducing gut inflammation, ginger can alleviate the underlying irritation that might trigger nausea signals.

-

Antioxidant Properties: The active compounds in ginger are powerful antioxidants, capable of scavenging harmful free radicals that can cause cellular damage and contribute to inflammation and gastrointestinal distress. This protective effect may indirectly contribute to its anti-nausea properties.

-

Direct Action on the Gut: Beyond systemic effects, ginger may have direct, local effects on the lining of the stomach and intestines, potentially soothing irritation and protecting the mucosal barrier.

-

Central Nervous System Modulation (Possible): While less understood than its peripheral actions, some research suggests ginger might also have direct effects on the central nervous system, influencing the vomiting center itself, although the precise mechanisms are still under investigation. Some studies propose it might modulate other neurotransmitter systems, such as dopamine, histamine, or acetylcholine, which are also implicated in nausea.

The beauty of ginger’s mechanism lies in its holistic nature. It doesn’t just block one pathway; it addresses multiple facets of the nausea experience, from the initial trigger in the gut to the brain’s interpretation of distress signals. This synergistic action of its diverse bioactive compounds is what makes it such a broad-spectrum and effective anti-emetic, truly a masterpiece of natural pharmacology.

Scientific Validation: Modern Evidence for an Ancient Remedy

The shift from anecdotal evidence to rigorous scientific inquiry has been a defining characteristic of modern medicine. For ginger, this transition has been overwhelmingly positive, with a wealth of studies affirming what traditional healers knew intuitively for millennia. The scientific community has increasingly validated ginger’s efficacy across various types of nausea, cementing its status as a credible therapeutic agent.

Motion Sickness:

One of the earliest and most consistently supported applications of ginger is in the prevention and treatment of motion sickness. Numerous double-blind, placebo-controlled trials have demonstrated ginger’s superiority over placebo and, in some cases, comparable efficacy to conventional anti-emetics like dimenhydrinate (Dramamine), but with fewer side effects. Studies involving sea travel, car journeys, and even simulated motion in laboratories have shown that ginger significantly reduces symptoms such as dizziness, cold sweats, and the sensation of nausea. The typical effective dose for motion sickness is often around 1 gram of ginger powder, taken 30 minutes to an hour before travel.

Morning Sickness (Pregnancy-Related Nausea and Vomiting):

Perhaps one of the most celebrated and well-researched uses of ginger is for the common discomfort of morning sickness, which affects up to 80% of pregnant women. Research has consistently shown ginger to be a safe and effective remedy, particularly for mild to moderate nausea. Meta-analyses of multiple clinical trials have concluded that ginger is more effective than placebo in reducing the severity and frequency of nausea and vomiting during pregnancy. Its safety profile for both mother and fetus is a significant advantage, making it a preferred option for many healthcare providers before resorting to pharmaceutical interventions. Recommended dosages typically range from 250 mg to 1 gram per day, often divided into several doses.

Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting (CINV):

CINV is one of the most distressing side effects of cancer treatment, significantly impacting patients’ quality of life and adherence to therapy. While powerful anti-emetic drugs are available, ginger has shown promise as an adjunct therapy, particularly for reducing the severity of delayed nausea (nausea occurring 24 hours or more after chemotherapy) and anticipatory nausea. Studies indicate that when added to conventional anti-emetic regimens, ginger can further reduce the intensity and frequency of nausea. The mechanism is thought to involve its 5-HT3 receptor antagonist activity, similar to some conventional drugs. Dosages often range from 0.5 to 2 grams per day, usually started a few days before chemotherapy and continued for several days after. It’s crucial for patients to discuss ginger supplementation with their oncologists due to potential interactions with other medications.

Post-Operative Nausea and Vomiting (PONV):

PONV remains a common and unpleasant complication of surgery, affecting a significant proportion of patients. Several studies have investigated ginger’s role in PONV prevention and treatment. Meta-analyses have concluded that ginger can be effective in reducing the incidence and severity of PONV, often comparable to conventional anti-emetics but with fewer side effects like sedation. Its ability to act as a broad-spectrum anti-emetic without causing drowsiness makes it an attractive option for post-surgical recovery. Doses of 1-2 grams of ginger powder taken pre-operatively are often studied.

Other Nausea Types:

Beyond these major categories, preliminary research and anecdotal evidence suggest ginger’s utility for other forms of nausea, including:

- Migraine-related nausea: Some studies indicate ginger may help alleviate both the headache and associated nausea.

- General gastrointestinal upset: For indigestion, gas, and stomach cramps, ginger’s prokinetic and anti-inflammatory properties offer relief.

- Vertigo and Dizziness: Its action on the vestibular system may contribute to its efficacy.

Meta-Analyses and Systematic Reviews:

The culmination of this scientific scrutiny is often found in meta-analyses and systematic reviews, which synthesize data from multiple high-quality studies. These comprehensive reviews consistently support ginger’s efficacy across various nausea types, frequently highlighting its favorable safety profile compared to pharmaceutical alternatives. This robust body of evidence firmly positions ginger as a scientifically validated anti-emetic, bridging the gap between ancient wisdom and modern medical practice.

From Root to Remedy: Practical Applications and Considerations

With scientific validation firmly established, the practical integration of ginger into daily life for managing nausea becomes a matter of understanding its various forms, appropriate dosages, and potential precautions.

Forms of Ginger:

Ginger’s versatility means it can be consumed in numerous ways, each offering slightly different benefits and potencies:

- Fresh Ginger Root: The most natural form. It can be grated, sliced, or minced and added to hot water for a soothing tea, incorporated into smoothies, or used in cooking. Fresh ginger contains higher levels of gingerols.

- Preparation: For tea, steep 1-2 teaspoons of grated fresh ginger in a cup of hot water for 5-10 minutes.

- Dried Ginger Powder: Often more potent in shogaols due to the drying process. Convenient for capsules, teas, or as a spice.

- Capsules: A standardized and convenient way to consume precise doses.

- Powdered Tea: Mix a small amount into hot water.

- Ginger Chews/Candies: A popular option for motion sickness or mild nausea. Ensure they contain actual ginger extract, not just flavorings.

- Ginger Ale: Caution is advised. Most commercial ginger ales contain very little actual ginger and are primarily sugar and artificial flavors. While the carbonation might offer some temporary relief, they are generally not an effective source of medicinal ginger. Seek out artisanal or specialty ginger beers with real ginger content.

- Ginger Extracts/Tinctures: Concentrated liquid forms that offer precise dosing and rapid absorption.

Dosage Guidelines:

While specific dosages can vary, general recommendations based on research include:

- Motion Sickness: 1-2 grams of ginger powder (or equivalent fresh ginger) taken 30 minutes to 1 hour before travel, with subsequent doses every 4 hours if needed, up to 4 grams per day.

- Morning Sickness: 250 mg of ginger powder (or equivalent) four times a day, or 1 gram once daily.

- Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea: 0.5-1 gram of ginger powder, taken 30 minutes before chemotherapy and continued for 3-5 days after, in conjunction with conventional anti-emetics.

- Post-Operative Nausea: 1-2 grams of ginger powder given 1 hour before surgery.

- General Nausea/Indigestion: 250 mg to 1 gram of ginger powder, 2-3 times daily, or as needed.

Always consult a healthcare professional before starting any new supplement, especially if pregnant, undergoing chemotherapy, or taking other medications.

Synergistic Use and Integration:

Ginger often works beautifully as a standalone remedy for mild nausea or as an adjunctive therapy alongside conventional medicine for more severe cases. Its gentle nature makes it compatible with many other treatments, offering an added layer of relief without significant drug interactions in most healthy individuals.

When Not to Use Ginger (Cautions and Contraindications):

While generally recognized as safe (GRAS) by regulatory bodies, ginger is not without its considerations, especially at higher doses or in specific medical conditions:

- Blood Thinners (Anticoagulants/Antiplatelets): Ginger can have mild antiplatelet effects, potentially increasing the risk of bleeding when taken with drugs like warfarin, aspirin, or clopidogrel. Patients on these medications should use ginger cautiously and under medical supervision.

- Gallstones: Ginger stimulates bile production and flow. Individuals with gallstones should exercise caution, as this could potentially trigger a gallbladder attack.

- Diabetes Medication: High doses of ginger might lower blood sugar levels, potentially enhancing the effects of anti-diabetic drugs and leading to hypoglycemia.

- Heart Conditions: In very high doses, ginger might affect heart rhythm or blood pressure, although this is rare with typical therapeutic amounts.

- Surgery: Due to its potential antiplatelet effects, it is generally recommended to discontinue ginger supplements at least two weeks before any scheduled surgery.

- Gastrointestinal Irritation: While generally soothing, very high doses of ginger can sometimes cause heartburn or stomach upset in sensitive individuals.

- Individual Sensitivities/Allergies: Although rare, allergic reactions to ginger can occur.

Quality and Sourcing:

When purchasing ginger supplements (capsules, extracts), choose reputable brands that conduct third-party testing for purity and potency. This ensures you are getting a product free from contaminants and with a consistent amount of active compounds. For fresh ginger, look for firm, smooth roots without any mold or soft spots.

By understanding these practical aspects, individuals can confidently and safely harness the power of this remarkable root, integrating an age-old remedy into modern health strategies.

The Future of Ginger: Beyond Nausea

The story of ginger does not end with its established role as an anti-nausea powerhouse. The same bioactive compounds and multi-targeted mechanisms that quell an upset stomach are now being vigorously investigated for a much broader spectrum of therapeutic applications, hinting at an even richer future for this ancient root.

Expanding Research Frontiers:

Scientists are increasingly exploring ginger’s potential in areas far beyond emesis:

- Anti-inflammatory and Pain Relief: Ginger’s potent anti-inflammatory properties are being studied for conditions like osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and muscle pain. Its ability to inhibit COX-2 and other inflammatory pathways positions it as a natural alternative or adjunct to conventional pain management.

- Anti-cancer Properties: Preliminary research, primarily in cell culture and animal models, suggests gingerols and shogaols may possess anti-cancer properties, including inhibiting cancer cell growth, inducing apoptosis (programmed cell death), and preventing metastasis in various cancer types (colorectal, ovarian, prostate, breast). While exciting, these findings are still in early stages and require human clinical trials.

- Anti-diabetic Effects: Some studies indicate ginger may help improve insulin sensitivity, lower blood sugar levels, and reduce markers of oxidative stress in individuals with diabetes, although more research is needed to confirm these effects and establish safe dosages.

- Cardiovascular Health: Ginger has shown potential in lowering cholesterol levels, reducing blood pressure, and preventing blood clot formation, contributing to overall cardiovascular well-being.

- Neuroprotective Properties: Emerging research suggests ginger may have protective effects on brain health, potentially beneficial in conditions like Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, due to its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory actions.

- Digestive Health Beyond Nausea: Its prokinetic effects, anti-inflammatory actions, and ability to stimulate digestive enzymes make it valuable for overall gut health, addressing issues like indigestion, bloating, and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

Integration into Modern Healthcare:

As the scientific evidence accumulates, ginger is moving from the fringes of alternative medicine to a more integrated role within conventional healthcare. Its acceptance is growing among medical professionals who are increasingly open to evidence-based natural remedies, particularly those with a favorable safety profile. This integration is likely to lead to more standardized ginger formulations, clearer dosage guidelines, and its inclusion in comprehensive treatment plans, often in combination with pharmaceutical drugs to enhance efficacy or reduce side effects.

Sustainable Sourcing and Personalized Medicine:

The growing global demand for ginger also brings with it considerations of sustainable cultivation and ethical sourcing. Ensuring that ginger production benefits local communities and preserves ecological balance will be crucial. Furthermore, the future of ginger research may delve into personalized medicine, exploring how individual genetic variations or microbiome compositions might influence responses to ginger, allowing for tailored therapeutic approaches.

The journey of ginger is far from over. From its ancient roots as a revered spice and medicine to its current status as a scientifically validated therapeutic agent, and now to its promising future in diverse health applications, ginger continues to unfold its remarkable story. It stands as a powerful testament to the enduring wisdom of nature and the harmonious potential between traditional knowledge and modern scientific inquiry.

Conclusion: A Timeless Narrative of Healing

The tale of ginger and nausea is more than just a recounting of botanical properties; it is a timeless narrative of human resilience, cultural exchange, and the enduring quest for comfort. From the bustling marketplaces of ancient Asia to the sophisticated laboratories of modern science, ginger has traversed millennia, its fiery essence consistently offering solace against the discomfort of an unsettled stomach.

We have journeyed through its rich history, witnessing its reverence in ancient Ayurvedic and Traditional Chinese Medicine, its global spread through trade routes, and its steadfast presence in folk remedies across generations. We’ve unraveled the complex physiological enigma of nausea, understanding the intricate dance of neurotransmitters and brain pathways that ginger so deftly modulates. And crucially, we’ve explored the robust scientific evidence that now unequivocally validates what our ancestors knew instinctively: that ginger, with its multifaceted arsenal of gingerols and shogaols, is a remarkably effective, safe, and gentle anti-emetic.

Whether it’s the queasy onset of morning sickness, the debilitating churn of chemotherapy, the disorienting sway of motion, or the lingering unease after surgery, ginger stands ready, a testament to the harmony between traditional wisdom and contemporary scientific rigor. It is not a fleeting trend but a foundational remedy, a powerful reminder that sometimes, the most effective solutions are those that have been patiently refined by time itself. As we continue to explore its broader therapeutic potential, ginger remains, first and foremost, the age-old remedy for nausea that still works, a warm, reassuring presence in the ongoing human story of healing.