Get Gut-Healthy: The Fiber-Rich Beans That Feed Your Microbiome

In an era increasingly defined by the search for wellness, the spotlight has swung firmly onto an often-overlooked, yet profoundly influential, part of our anatomy: the gut. Far from being a mere digestive tube, our gut, and more specifically, the trillions of microorganisms residing within it – our microbiome – is now recognized as a bustling metropolis of life, a "second brain" that dictates not just our digestion, but our immunity, mood, metabolism, and even our propensity for chronic disease.

Yet, despite this burgeoning understanding, many of us inadvertently starve this vital inner ecosystem. Our modern diets, often devoid of the complex carbohydrates and fibers our gut microbes crave, leave them malnourished, leading to an imbalance known as dysbiosis. This article embarks on a journey to unravel the intricate relationship between our diet and our microbiome, spotlighting the humble, yet extraordinarily potent, bean as a cornerstone of gut health. We will delve into the science of why beans are not just good, but essential, for cultivating a thriving inner garden, exploring their unique fiber profile, the magic of short-chain fatty acids, and practical ways to integrate these nutritional powerhouses into your life.

The Microbiome Unveiled: An Inner Universe

Imagine a vibrant, teeming rainforest inside you, an ecosystem of unparalleled complexity and diversity. This is your gut microbiome. Comprising bacteria, viruses, fungi, and other microorganisms, it weighs roughly 2-5 pounds and contains more genetic material than the entire human genome. Far from being passive inhabitants, these microbes are active participants in nearly every aspect of our health.

Their roles are myriad and profound:

- Digestion and Nutrient Absorption: While we can digest many foods, our microbes specialize in breaking down complex carbohydrates and fibers that our own enzymes cannot. In doing so, they unlock nutrients and produce beneficial compounds.

- Immune System Modulation: A significant portion of our immune system resides in the gut. The microbiome trains and regulates immune cells, distinguishing between harmful pathogens and beneficial residents, thereby preventing overreactions (allergies, autoimmune conditions) and ensuring a robust defense against illness.

- Vitamin Synthesis: Certain gut bacteria synthesize essential vitamins, such as B vitamins (B12, folate, biotin, riboflavin) and vitamin K, contributing directly to our nutritional status.

- Neurotransmitter Production: Astonishingly, many neurotransmitters, including serotonin (a key regulator of mood and sleep), are produced in the gut. This forms the basis of the "gut-brain axis," a bidirectional communication highway linking gut health to mental well-being.

- Protection Against Pathogens: A diverse and healthy microbiome creates a competitive environment, preventing harmful bacteria from colonizing and causing disease. It acts as a protective barrier.

When this delicate balance is disrupted – through poor diet, stress, antibiotics, or environmental toxins – dysbiosis sets in. A less diverse, less functional microbiome is linked to a startling array of conditions: irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), obesity, type 2 diabetes, allergies, autoimmune diseases, anxiety, depression, and even neurological disorders like Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s. The key to restoring balance and fostering health lies in providing our microbial residents with the fuel they need to flourish.

Fiber: The Unsung Hero and the Microbiome’s Feast

For decades, dietary fiber was viewed primarily as a laxative – a substance to "keep things moving." While true, this understanding barely scratches the surface of fiber’s incredible importance, especially for our gut microbiome. Fiber, by definition, is a type of carbohydrate that our human digestive enzymes cannot break down. It passes largely intact into the large intestine, where it becomes the primary food source for our beneficial gut bacteria.

Not all fiber is created equal, however. We broadly categorize fiber into soluble and insoluble forms:

- Insoluble Fiber: This type adds bulk to stool and helps food pass more quickly through the digestive system, preventing constipation. Think of it as the scaffolding that supports digestive transit.

- Soluble Fiber: This fiber dissolves in water to form a gel-like substance. It slows down digestion, helps regulate blood sugar, and can lower cholesterol. Crucially, soluble fiber is often highly fermentable, making it a prime food source for gut bacteria.

But the real star for the microbiome is a special type of fiber known as prebiotic fiber. Prebiotics are specific types of non-digestible food ingredients that selectively stimulate the growth and/or activity of beneficial bacteria in the colon. They are the fertilizer for our inner garden, preferentially feeding the "good guys" like Bifidobacteria and Lactobacillus.

Within the realm of prebiotic fibers, Resistant Starch (RS) stands out as a particularly potent player, and it is here that beans shine brightest. Resistant starch, as its name suggests, "resists" digestion in the small intestine and arrives intact in the large intestine, where it is enthusiastically fermented by gut bacteria. There are several types of resistant starch:

- RS1 (Physically Inaccessible Starch): Found in whole grains, seeds, and legumes, encased within cell walls.

- RS2 (Native Granular Starch): Found in raw potatoes, green bananas, and high-amylose corn.

- RS3 (Retrograded Starch): Formed when starchy foods like potatoes, rice, and beans are cooked and then cooled. This cooling process changes the starch structure, making it more resistant to digestion.

- RS4 (Chemically Modified Starch): Industrially produced.

- RS5 (Amylose-Lipid Complexes): Formed when amylose (a component of starch) interacts with lipids.

Beans are rich in RS1 and, significantly, become a potent source of RS3 when cooked and then cooled. This means that a bean salad or leftover chili can be even more gut-healthy than freshly cooked beans! When our gut bacteria ferment these complex fibers, they don’t just "eat" them; they transform them into incredibly beneficial compounds: Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs).

SCFAs: The Gut’s Golden Currency

The production of Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs) is perhaps the most profound benefit of feeding our microbiome with fiber-rich foods like beans. These organic acids – primarily acetate, propionate, and butyrate – are not merely waste products; they are potent signaling molecules and crucial energy sources that exert wide-ranging effects on our health, both locally within the gut and systemically throughout the body.

Let’s break down the power of each:

-

Butyrate: The Gut Guardian

- Primary Fuel for Colonocytes: Butyrate is the preferred energy source for the cells lining the colon (colonocytes). A steady supply of butyrate ensures these cells are healthy and functional.

- Maintains Gut Barrier Integrity: A robust gut barrier (often referred to as the "intestinal wall") is critical. It acts as a selective filter, allowing nutrients to pass while blocking harmful toxins, undigested food particles, and pathogens from entering the bloodstream. Butyrate strengthens this barrier, reducing "leaky gut" (increased intestinal permeability) and its associated systemic inflammation.

- Anti-inflammatory Properties: Butyrate directly modulates immune responses in the gut, reducing inflammation. This is particularly relevant in conditions like Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), where chronic inflammation is a hallmark.

- Cancer Protection: Research suggests butyrate may play a role in preventing colorectal cancer by promoting programmed cell death (apoptosis) in cancerous cells and inhibiting their proliferation.

-

Acetate: The Systemic Stabilizer

- Energy Source Beyond the Colon: While some acetate is used locally, a significant portion travels through the bloodstream to the liver and other tissues, where it can be used for energy or converted into lipids.

- Satiety and Appetite Regulation: Acetate has been linked to increased satiety and reduced appetite, potentially by influencing hormones involved in hunger signaling.

- Metabolic Health: Some research suggests acetate may play a role in improving insulin sensitivity and regulating blood sugar levels, contributing to overall metabolic health.

-

Propionate: The Metabolic Modulator

- Liver Health and Glucose Homeostasis: Propionate is primarily absorbed and metabolized by the liver. It plays a role in gluconeogenesis (the production of glucose) and can influence cholesterol synthesis.

- Appetite Suppression: Like acetate, propionate has been shown to have appetite-suppressing effects, potentially by stimulating the release of gut hormones that signal fullness.

- Immune Modulation: Emerging research indicates propionate can also influence immune responses, potentially having anti-inflammatory effects and even impacting brain function.

The collective impact of these SCFAs is nothing short of revolutionary. They are the direct link between the food we eat, the microbes we cultivate, and the health benefits we experience. They underscore why feeding our microbiome with fermentable fibers is not just a dietary recommendation but a fundamental strategy for overall well-being.

Beans: Nature’s Potent Prebiotic Powerhouses

Now, let’s turn our attention to the unsung heroes of gut health: beans. Often overlooked, sometimes maligned for their gas-producing potential, beans are, in fact, nutritional titans. They are the quintessential "slow food" for your gut, providing a sustained release of prebiotics that keeps your microbial community happy and diverse.

What makes beans so exceptional for the microbiome?

- Rich in Diverse Fiber: Beans boast an impressive array of both soluble and insoluble fibers. More importantly, they are one of the richest sources of resistant starch (RS1 and RS3, especially when cooled), making them a prime fuel source for butyrate-producing bacteria. A single cup of cooked black beans can contain over 15 grams of fiber, a significant chunk of the recommended daily intake.

- Protein Powerhouses: Beyond fiber, beans are excellent plant-based protein sources, making them a staple for vegetarians and a valuable addition to any diet. This protein contributes to satiety and muscle maintenance.

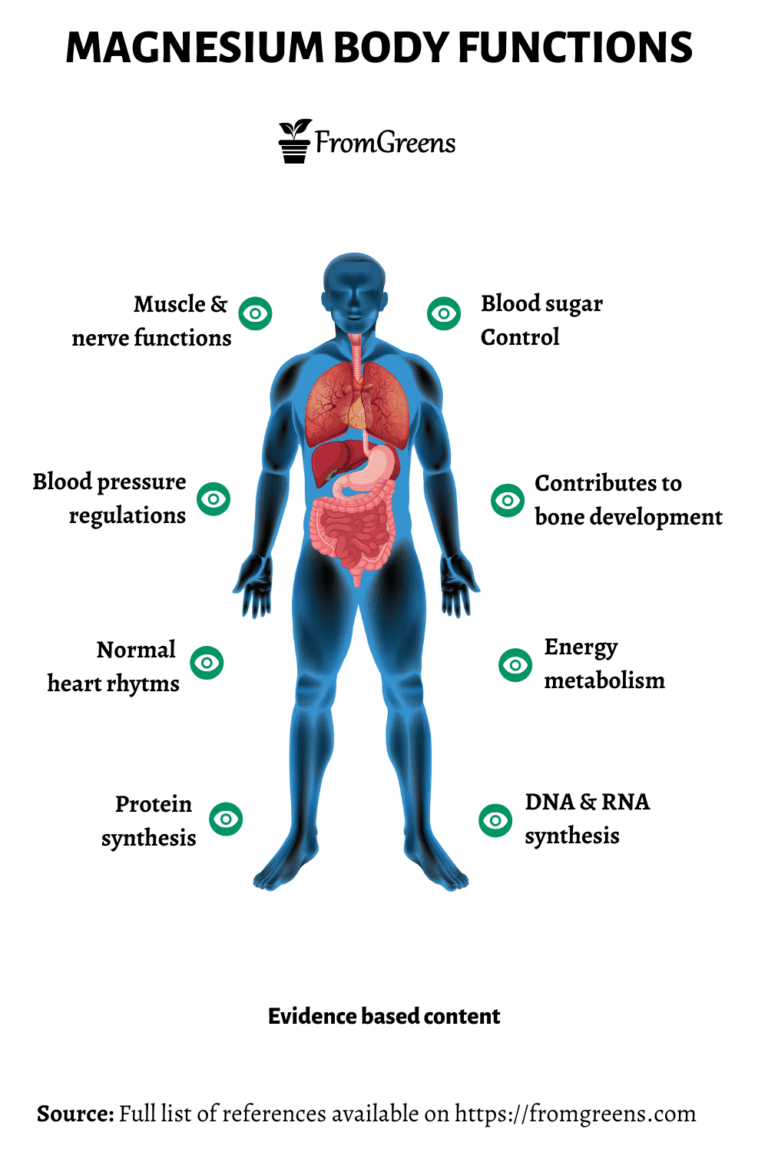

- Micronutrient Magnets: Beans are packed with essential vitamins and minerals, including folate (crucial for DNA synthesis and repair), iron (vital for oxygen transport), magnesium (involved in over 300 biochemical reactions), potassium (important for blood pressure regulation), and zinc (for immune function).

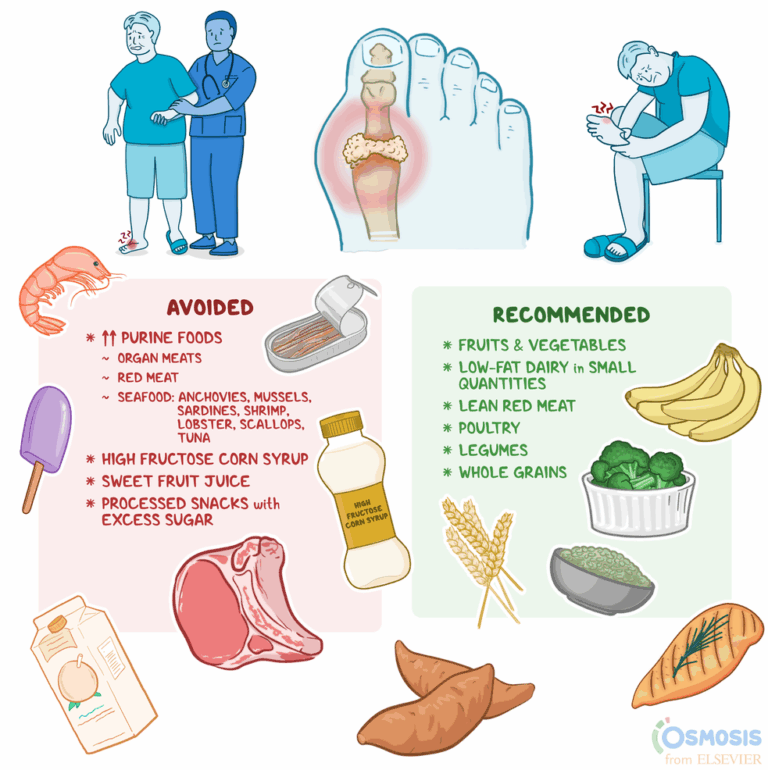

- Antioxidant Abundance: Many varieties of beans, particularly darker ones like black beans and kidney beans, are rich in polyphenols and other antioxidants. These compounds combat oxidative stress in the body, reduce inflammation, and may even have synergistic effects with the gut microbiome, further enhancing gut barrier function and SCFA production.

Let’s explore some popular bean varieties and their specific contributions:

- Black Beans: A staple in Latin American cuisine, black beans are renowned for their dark color, indicative of their high anthocyanin content – potent antioxidants. They are particularly rich in resistant starch and soluble fiber, making them excellent for blood sugar control and feeding Bifidobacteria.

- Kidney Beans: Named for their distinctive shape, kidney beans are another excellent source of resistant starch and soluble fiber. They have a hearty texture and absorb flavors well, making them ideal for chilis and stews.

- Chickpeas (Garbanzo Beans): Versatile and beloved in Middle Eastern and Mediterranean cooking, chickpeas offer a balanced profile of soluble and insoluble fiber, along with resistant starch. They are fantastic for hummus, salads, and roasted snacks.

- Lentils: Though technically legumes rather than beans, lentils deserve an honorable mention due to their similar nutritional profile and rapid cooking time. They are packed with fiber, protein, and folate, making them incredibly gut-friendly and easy to incorporate into soups, dals, and salads.

- Cannellini Beans (White Kidney Beans): These creamy, mild-flavored beans are perfect for purees, soups, and salads. They provide a good dose of soluble fiber and resistant starch, contributing to a healthy microbiome.

- Pinto Beans: A favorite in Southwestern and Mexican cuisine, pinto beans are creamy when cooked and offer a substantial amount of fiber and protein. They are a reliable source of prebiotics for your gut microbes.

Addressing the "Anti-Nutrient" Elephant in the Room

A common concern raised about beans and other legumes revolves around "anti-nutrients" such as lectins and phytates. It’s true that these compounds exist in raw or improperly prepared beans, and in high amounts, they can interfere with nutrient absorption or cause digestive distress. However, for a knowledgeable audience, it’s crucial to understand the nuances:

- Lectins: These are carbohydrate-binding proteins found in many plants, including beans. While some lectins can be problematic (e.g., phytohaemagglutinin in raw red kidney beans), they are largely destroyed by proper cooking methods. Soaking, boiling, and pressure cooking effectively denature most lectins, rendering beans perfectly safe and beneficial.

- Phytates (Phytic Acid): Phytates can bind to minerals like iron, zinc, and calcium, potentially reducing their absorption. However, phytates also have antioxidant properties and emerging research suggests they may even have anti-cancer effects. Furthermore, proper preparation (soaking, sprouting, fermentation) significantly reduces phytate levels. The fermentation activity of gut microbes themselves can also help break down phytates, making minerals more bioavailable over time.

The net benefit of consuming properly prepared beans far outweighs any potential negative effects from these compounds. The vast majority of people consume beans without issue, and the gut health benefits, particularly the production of SCFAs, are profound. The fear surrounding "anti-nutrients" is largely overblown when considering standard culinary practices.

The Art of Integration: Weaving Beans into Your Life

Embarking on a journey to incorporate more beans into your diet requires a bit of strategy, especially if your gut microbiome is not accustomed to such a rich fiber source. Remember, the goal is to feed your microbiome, not overwhelm it.

1. Start Slowly and Gradually Increase:

If you’re not a regular bean-eater, begin with small portions (e.g., a quarter-cup serving) and gradually increase over several weeks. This allows your gut microbes time to adapt and multiply, building up the necessary enzymatic machinery to process the increased fiber.

2. Proper Preparation is Key:

- Soaking: For dried beans, soaking for at least 8-12 hours (and discarding the soaking water) significantly reduces oligosaccharides (complex sugars that can cause gas) and helps break down anti-nutrients.

- Cooking from Scratch: While canned beans are convenient, cooking from dried beans often results in a better texture and potentially a slightly higher resistant starch content. Ensure beans are cooked thoroughly until soft.

- Rinsing Canned Beans: Always rinse canned beans thoroughly under cold water. This removes excess sodium and some of the gas-producing oligosaccharides.

3. Embrace Culinary Versatility:

Beans are incredibly adaptable. Think beyond chili!

- Soups and Stews: Add a can of rinsed cannellini beans to vegetable soup, or black beans to a hearty stew.

- Salads: Toss chickpeas, black beans, or kidney beans into your favorite green or grain salad for an instant protein and fiber boost.

- Dips and Spreads: Hummus (made from chickpeas) is a classic. Explore other bean dips like black bean dip or white bean and rosemary spread.

- Main Dishes: Create bean burgers, use lentils as a meat substitute in tacos or bolognese, or make a vibrant bean and veggie curry.

- Sides: Serve seasoned black beans alongside roasted vegetables or grilled proteins.

- Baking: Believe it or not, pureed black beans can be an excellent addition to brownies or cakes, adding moisture and nutrients without altering flavor significantly.

- Breakfast: Consider a savory breakfast bowl with black beans, avocado, and eggs, or add lentils to a morning scramble.

4. Combine with Other Gut-Friendly Foods:

Pair beans with other prebiotic-rich foods like onions, garlic, leeks, and asparagus. Incorporate fermented foods (sauerkraut, kimchi, yogurt, kefir) to introduce beneficial bacteria, working synergistically with the prebiotics from beans.

Navigating the "Bean Bloat" Phenomenon

Let’s address the elephant in the room: gas and bloating. For many, the apprehension around consuming beans stems from this very real, albeit temporary, side effect. Understanding why it happens is key to overcoming it.

When you introduce a significant amount of fermentable fiber, like that found in beans, your existing gut bacteria, particularly those that thrive on these fibers, begin to feast. The byproduct of this fermentation process is gas (hydrogen, methane, and carbon dioxide). If your microbiome isn’t accustomed to processing these fibers, or if you introduce too much too quickly, the gas production can be excessive, leading to bloating, discomfort, and flatulence.

This is not necessarily a bad sign; it’s a sign of activity! It indicates that your microbes are working, producing those beneficial SCFAs. Over time, as your microbiome adapts to the increased fiber intake, the population of gas-producing bacteria may shift, and your gut will become more efficient at processing the fibers, leading to less discomfort.

Tips to minimize discomfort:

- Gradual Introduction: As mentioned, start small and increase slowly.

- Thorough Cooking: Ensure beans are very soft. Undercooked beans are harder to digest.

- Rinsing: Rinse canned beans well.

- Herbs and Spices: Certain herbs and spices, like ginger, fennel, cumin, and caraway seeds, have carminative properties that can help reduce gas. Add them generously to your bean dishes.

- Enzyme Supplements: Alpha-galactosidase enzyme supplements (e.g., Beano) can help break down the complex sugars in beans before they reach the colon, reducing gas production.

- Hydration: Drink plenty of water throughout the day.

- Chew Thoroughly: Proper chewing begins the digestive process and can reduce the burden on your gut.

Beyond Beans: A Holistic Gut-Healthy Lifestyle

While beans are phenomenal, they are one piece of a larger, intricate puzzle. A truly gut-healthy lifestyle encompasses a broader approach:

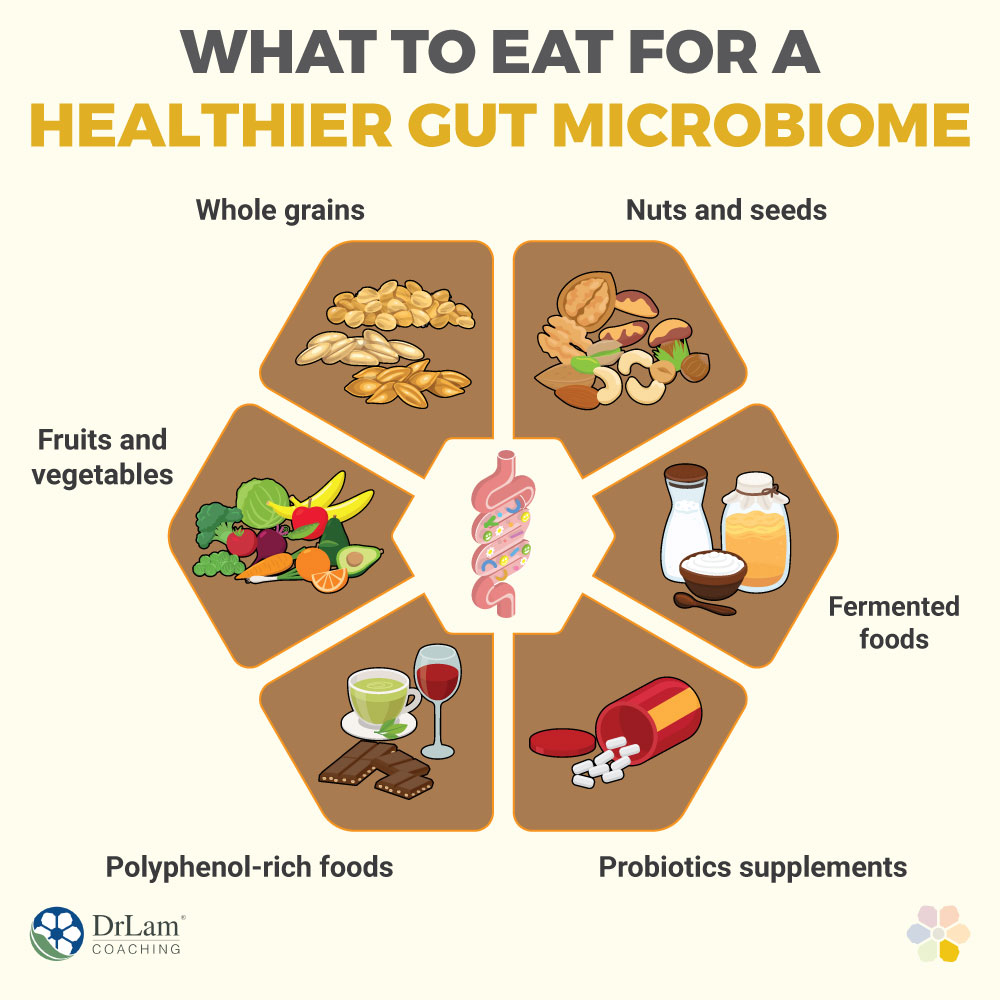

- Dietary Diversity: Aim for a wide variety of plant foods. Each plant brings a unique array of fibers and phytochemicals that feed different species of bacteria, fostering a more diverse and resilient microbiome. Include other prebiotic foods like onions, garlic, leeks, asparagus, Jerusalem artichokes, unripe bananas, apples, oats, and barley.

- Fermented Foods: Regularly consume fermented foods rich in live active cultures (probiotics) such as yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut, kimchi, kombucha, and tempeh. These introduce beneficial bacteria directly into your gut.

- Minimize Ultra-Processed Foods: These foods are typically high in unhealthy fats, sugar, and artificial additives, and often lack fiber, all of which can negatively impact the microbiome and promote inflammation.

- Stay Hydrated: Water is essential for maintaining the mucosal lining of the gut and facilitating regular bowel movements.

- Manage Stress: The gut-brain axis means stress directly impacts gut function. Practices like mindfulness, meditation, yoga, or spending time in nature can significantly benefit gut health.

- Prioritize Sleep: Poor sleep can disrupt circadian rhythms, which in turn can negatively affect the microbiome. Aim for 7-9 hours of quality sleep per night.

- Regular Exercise: Physical activity has been shown to increase microbial diversity and promote the growth of beneficial bacteria.

- Limit Unnecessary Antibiotics: While sometimes life-saving, antibiotics are broad-spectrum and decimate both harmful and beneficial gut bacteria. Use them judiciously and focus on gut repair strategies post-treatment.

The Future of Gut Health: A Personalized Journey

The science of the microbiome is still rapidly evolving, and what constitutes an "optimal" microbiome is likely highly individual. Factors like genetics, geography, early life experiences, and long-term dietary patterns all play a role. Therefore, the journey to gut health is a personalized one.

Listen to your body. Pay attention to how different foods make you feel. Experiment with different types of beans and preparation methods. Keep a food diary if you’re trying to identify triggers or track progress. Consult with a registered dietitian or healthcare professional experienced in gut health if you have persistent digestive issues.

Conclusion: A Return to Roots, A Path to Health

The story of the gut microbiome is a compelling narrative of interdependence. We provide the habitat and the food, and in return, our microscopic residents perform an astonishing array of functions vital for our survival and thriving. In this grand exchange, the humble bean emerges as a profound benefactor, offering a symphony of fibers, particularly resistant starch, that fuels the production of life-sustaining Short-Chain Fatty Acids.

By re-embracing these ancient, nutrient-dense legumes, we are not just adding a healthy component to our plates; we are actively cultivating a richer, more diverse, and more resilient inner ecosystem. We are moving beyond a simplistic view of nutrition to a sophisticated understanding of how food interacts with our biology at a microbial level.

So, let us shed the misconceptions and embrace the power of the bean. Let us commit to feeding our microbiome with the wisdom of whole foods, fostering a vibrant inner garden that blossoms into robust health, sharper minds, and a deeper connection to the intricate biology that defines us. The journey to a healthier gut begins, quite literally, with a handful of beans, paving the way for a healthier, more vibrant you.