The Whispers and Roars of the Joints: A Journey to Clarity on Rheumatoid Arthritis and Osteoarthritis

The human body is a marvel of engineering, an intricate symphony of bones, muscles, ligaments, and cartilage, all working in concert to facilitate movement, support, and protection. Yet, within this masterpiece, sometimes a discordant note emerges – the insidious, often debilitating reality of joint pain. For millions worldwide, this pain is not a fleeting ache but a persistent companion, a constant reminder of a body turning against itself or simply wearing down with the relentless march of time.

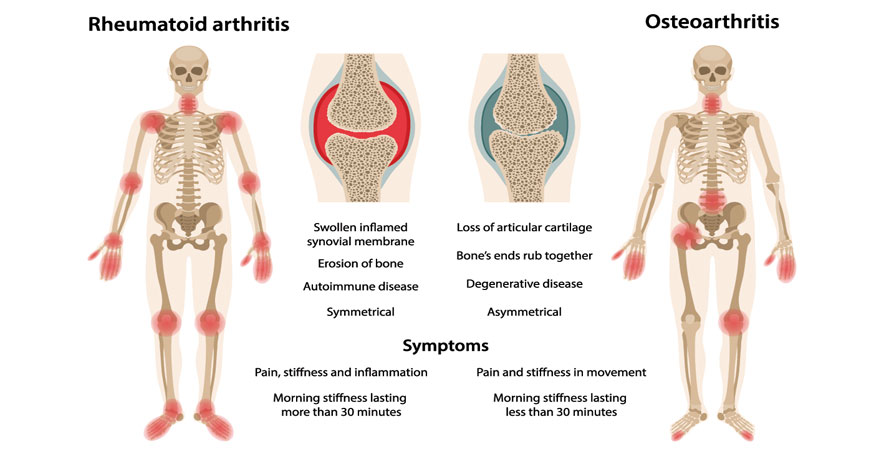

But what truly causes this suffering? Is all joint pain the same? The answer is a resounding no. Two of the most prevalent and often confused causes of chronic joint pain are Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) and Osteoarthritis (OA). While both conditions manifest as discomfort and stiffness in the joints, their underlying mechanisms, progression, and treatment approaches are as distinct as a whisper from a roar. To truly understand the difference is to embark on a journey of clarity, illuminating the paths to diagnosis, effective management, and ultimately, a better quality of life.

Chapter 1: The Initial Murmur – A Shared Experience, Divergent Paths

Imagine two individuals, Sarah and Mark, both in their late 40s, both waking up one morning to a new, unwelcome sensation in their hands. Sarah notices a stiffness that makes gripping her coffee mug difficult, a dull ache that seems to radiate from her knuckles. Mark experiences a similar stiffness, particularly after a long night’s sleep, but his pain feels more localized, a grating sensation primarily at the base of his thumb and in his knees after climbing stairs.

At first glance, their experiences might seem identical: joint pain, morning stiffness. This is where the initial confusion often arises, not just for patients, but sometimes even for healthcare providers unfamiliar with the subtle yet crucial distinctions. Both Sarah and Mark are experiencing symptoms of arthritis, a broad term that simply means "joint inflammation." But beneath this umbrella term lies a world of difference, a complex interplay of genetic predispositions, immune responses, mechanical stresses, and environmental factors.

For Sarah, her journey will likely lead to a diagnosis of Rheumatoid Arthritis – an autoimmune disease where her body’s immune system, designed to protect her from invaders, mistakenly attacks the healthy tissues of her joints. For Mark, his path points towards Osteoarthritis – a degenerative condition primarily characterized by the breakdown of the cartilage that cushions the ends of his bones. Their initial murmurs of pain, though similar in their immediate impact, are harbingers of fundamentally different narratives.

Chapter 2: Rheumatoid Arthritis – The Autoimmune Uprising

To understand Rheumatoid Arthritis, we must first appreciate the sophistication of the human immune system. It’s a highly trained army, constantly patrolling for foreign invaders like bacteria and viruses. In autoimmune diseases, this army suffers a catastrophic failure of intelligence, misidentifying its own country’s citizens – in this case, the synovial lining of the joints – as enemies.

The Genesis of the Attack:

RA typically begins insidiously, often in younger to middle-aged adults (though it can affect anyone at any age). It’s not a sudden event but a slow, gathering storm. Genetically predisposed individuals, perhaps triggered by an environmental factor like an infection or smoking, start producing autoantibodies – antibodies that target their own tissues. Two key players in this destructive process are Rheumatoid Factor (RF) and anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (anti-CCP). While not everyone with RA has these antibodies, their presence is a strong indicator of the disease.

The Battleground: The Synovium and Beyond:

The primary target in RA is the synovium, a thin membrane lining the inner surface of the joint capsule. The synovium produces synovial fluid, a viscous liquid that lubricates the joint and nourishes the cartilage. In RA, the misguided immune cells infiltrate the synovium, causing it to become inflamed, thickened, and overgrown. This inflamed tissue, called a pannus, behaves like a cancerous growth, aggressively invading and eroding the adjacent cartilage and bone.

Imagine the joint as a delicate engine. The synovium is the oil filter, and the synovial fluid is the oil. In RA, the filter itself becomes diseased, not only failing to do its job but actively producing corrosive substances that damage the engine’s vital parts.

The Clinical Symphony of RA:

- Symmetry is Key: One of the hallmarks of RA is its symmetrical presentation. If the knuckles on your right hand are affected, it’s highly likely the corresponding knuckles on your left hand will also be involved. This symmetry extends to wrists, knees, and ankles.

- Small Joints First: RA often preferentially attacks the small joints of the hands (metacarpophalangeal or MCP, and proximal interphalangeal or PIP joints, sparing the distal interphalangeal or DIP joints) and feet (metatarsophalangeal or MTP joints).

- Prolonged Morning Stiffness: Patients with RA describe morning stiffness that lasts for hours – often more than 30 minutes, sometimes several hours – and improves with movement. This is a crucial diagnostic differentiator.

- Swelling, Heat, and Redness: The inflammation is palpable. Joints appear swollen, feel warm to the touch, and can sometimes be red.

- Systemic Involvement: This is where RA truly distinguishes itself from OA. RA is not just a joint disease; it’s a systemic inflammatory disease. Patients often experience profound fatigue, low-grade fever, weight loss, and a general feeling of malaise. Inflammation can affect other organs, leading to conditions like rheumatoid nodules (lumps under the skin), pleurisy (lung inflammation), pericarditis (heart inflammation), vasculitis (blood vessel inflammation), and Sjögren’s syndrome (dry eyes and mouth).

- Fluctuating Course: RA often follows a pattern of flares and remissions. During a flare, symptoms worsen significantly, while during remission, they may subside partially or completely. However, even in remission, underlying damage can continue if not properly managed.

The Diagnostic Pursuit:

Diagnosing RA requires a combination of clinical evaluation, blood tests, and imaging. A rheumatologist, a specialist in autoimmune and musculoskeletal diseases, will look for:

- Clinical Presentation: Characteristic joint involvement, symmetry, morning stiffness, swelling.

- Blood Tests:

- Rheumatoid Factor (RF): Present in about 70-80% of RA patients, but can also be positive in other conditions or healthy individuals.

- Anti-CCP Antibodies: More specific for RA and can predict more severe disease.

- Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) and C-Reactive Protein (CRP): Non-specific markers of inflammation, elevated during flares.

- Imaging: X-rays can show joint space narrowing and bone erosions (damage) later in the disease. MRI and ultrasound can detect early inflammation and subtle damage.

The Treatment Philosophy: Early and Aggressive:

The goal of RA treatment is to suppress the overactive immune system, control inflammation, prevent joint damage, and preserve function. The advent of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) has revolutionized RA management.

- Traditional DMARDs: Methotrexate, sulfasalazine, hydroxychloroquine, and leflunomide are cornerstone treatments, working to dampen the immune response.

- Biologics: A newer class of DMARDs, biologics target specific molecules involved in the inflammatory pathway (e.g., TNF inhibitors, IL-6 inhibitors, B-cell depleters). They are highly effective but come with increased risks of infection.

- Corticosteroids: Prednisone is often used short-term during flares to rapidly reduce inflammation.

- NSAIDs: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g., ibuprofen, naproxen) help manage pain and inflammation but do not alter the disease course.

- Physical and Occupational Therapy: Crucial for maintaining joint mobility, strength, and adapting to daily tasks.

- Surgery: In severe cases, joint replacement or fusion may be necessary to correct deformities and alleviate pain.

The story of RA is one of an internal struggle, a body’s own defense system turning rogue. Early diagnosis and aggressive treatment are paramount to prevent irreversible joint damage and maintain quality of life.

Chapter 3: Osteoarthritis – The Wear and Tear Narrative

In stark contrast to RA’s autoimmune uprising, Osteoarthritis tells a different tale: one of mechanical stress, gradual degeneration, and the relentless march of time. OA is often described as "wear-and-tear arthritis," a simplistic but not entirely inaccurate description of a complex process involving the entire joint.

The Silent Erosion: Cartilage Breakdown:

The star player in the OA narrative is articular cartilage, the smooth, slippery tissue that covers the ends of bones within a joint. Its primary function is to reduce friction during movement and act as a shock absorber. In OA, this cartilage begins to break down, soften, and fray.

Imagine the cartilage as a protective, Teflon-like coating on two moving parts. Over time, due to repetitive stress, injury, or simply age, this coating starts to thin, crack, and eventually erode. As the cartilage wears away, the underlying bone becomes exposed. When bone rubs against bone, it creates friction, pain, and further damage.

The Body’s Response: Failed Repair:

The body attempts to repair this damage, but its efforts are often misguided. It tries to grow new bone at the margins of the joint, forming bony outgrowths called osteophytes or bone spurs. While these might initially be seen as a compensatory mechanism, they can restrict joint movement, impinge on nerves, and contribute to pain. The subchondral bone (the bone directly beneath the cartilage) also becomes denser and thicker (sclerosis), further altering joint mechanics.

The Clinical Profile of OA:

- Mechanical Pain: The pain in OA is typically "mechanical" in nature. It worsens with activity and weight-bearing, and improves with rest. Standing after prolonged sitting, climbing stairs, or walking long distances can exacerbate symptoms.

- Short-Lived Morning Stiffness: Unlike RA, morning stiffness in OA is usually brief, lasting less than 30 minutes, and improves relatively quickly with movement. It can also occur after periods of inactivity (known as "gelling phenomenon"), such as after sitting in a movie theater.

- Asymmetrical Presentation: OA can affect joints unilaterally (one side) or bilaterally, but not necessarily symmetrically. For example, it’s common to have OA in one knee due to an old injury, while the other knee remains unaffected for a long time.

- Weight-Bearing Joints and Hands: OA commonly affects the large, weight-bearing joints like the knees, hips, and spine. In the hands, it primarily targets the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints (the ones closest to the fingertips) and the base of the thumb (carpometacarpal or CMC joint), often leading to bony enlargements called Heberden’s nodes (DIP) and Bouchard’s nodes (PIP).

- Crepitus: A characteristic "creaking," "grinding," or "popping" sensation or sound (crepitus) can often be felt or heard as the roughened joint surfaces move against each other.

- No Systemic Symptoms: Crucially, OA is not a systemic inflammatory disease. Patients do not experience the fatigue, fever, weight loss, or organ involvement seen in RA. The inflammation, when present, is localized to the affected joint.

- Progressive, but Variable: OA is generally a progressive condition, meaning it tends to worsen over time. However, its progression is highly variable, with some individuals experiencing long periods of stable symptoms.

The Diagnostic Path:

Diagnosing OA is primarily based on clinical symptoms and imaging.

- Clinical Presentation: Characteristic pain patterns, stiffness, and joint involvement.

- Physical Examination: Tenderness over the joint, reduced range of motion, crepitus, and sometimes joint effusions (fluid accumulation).

- Imaging: X-rays are usually sufficient to diagnose OA, showing joint space narrowing (due to cartilage loss), osteophytes, and subchondral sclerosis. Blood tests are typically normal and are primarily used to rule out inflammatory conditions like RA.

The Treatment Philosophy: Manage Symptoms, Preserve Function:

Since OA is a degenerative condition, there is currently no cure to reverse cartilage damage. Treatment focuses on managing pain, improving function, and slowing progression.

- Lifestyle Modifications:

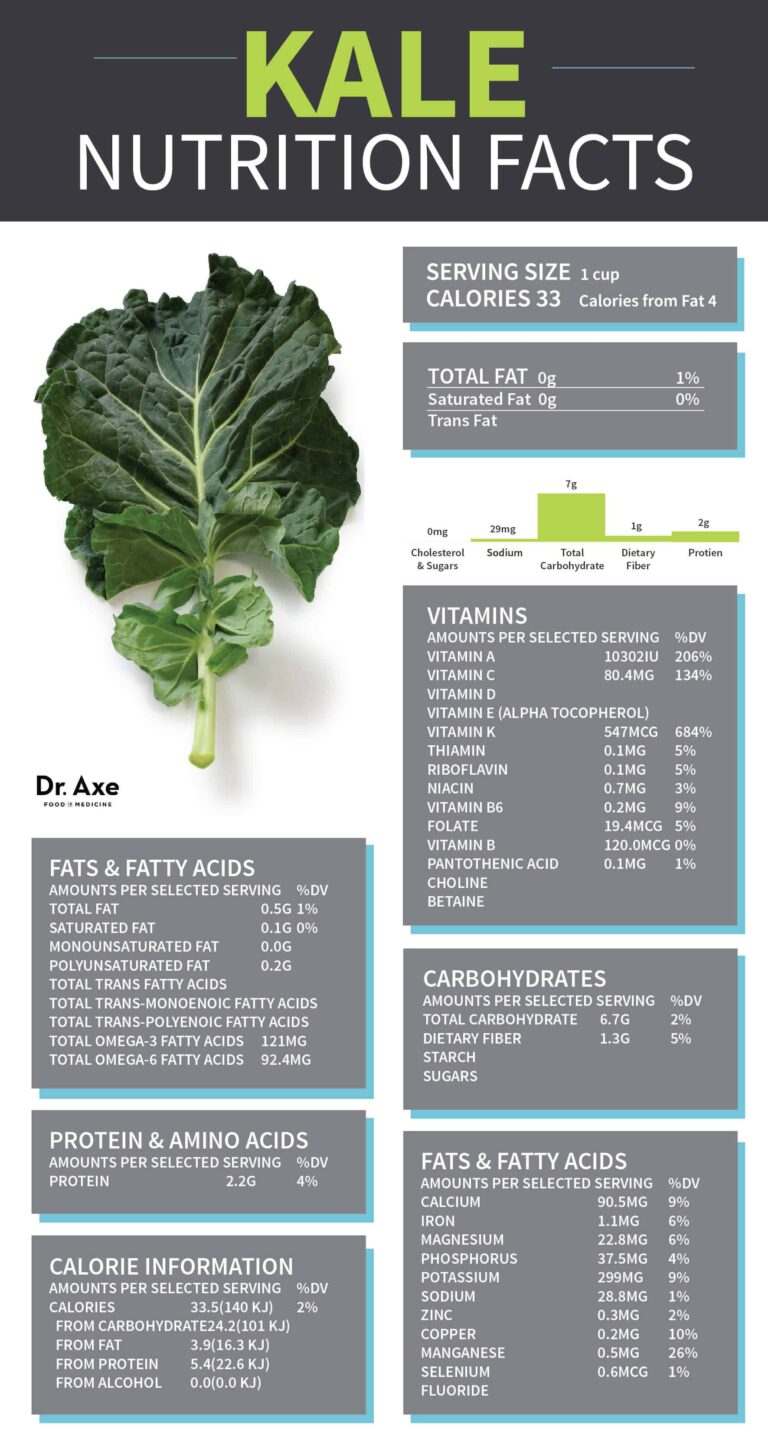

- Weight Management: Reducing excess weight significantly lessens the load on weight-bearing joints.

- Exercise: Low-impact activities like swimming, cycling, and walking strengthen muscles around the joint, improve flexibility, and maintain cartilage health.

- Assistive Devices: Canes, walkers, and braces can offload stress on painful joints.

- Pharmacological Treatments:

- Pain Relievers: Acetaminophen (paracetamol) is often the first line.

- NSAIDs: Oral or topical NSAIDs can reduce pain and localized inflammation.

- Topical Agents: Capsaicin cream or diclofenac gel can provide localized relief.

- Corticosteroid Injections: Can temporarily reduce inflammation and pain in a specific joint.

- Hyaluronic Acid Injections: "Viscosupplementation" injections aim to improve the lubricating properties of joint fluid, though their efficacy is debated.

- Physical and Occupational Therapy: Essential for strengthening muscles, improving range of motion, and learning joint-protective techniques.

- Surgery: For severe OA that doesn’t respond to conservative measures, surgical options include:

- Arthroscopy: To clean out debris or repair damaged cartilage (though its role in OA is limited).

- Osteotomy: Reshaping bone to shift weight bearing away from damaged areas.

- Arthroplasty (Joint Replacement): Replacing the damaged joint with a prosthetic implant (e.g., total knee replacement, total hip replacement), offering significant pain relief and improved function in end-stage disease.

The story of OA is one of wear and tear, a gradual breakdown of the body’s cushioning system. While irreversible, its impact can be significantly mitigated through proactive management and lifestyle adjustments.

Chapter 4: The Crucial Distinctions – A Side-by-Side Clarity

Having explored the individual narratives of RA and OA, the critical differences become strikingly clear. These distinctions are not merely academic; they dictate diagnostic pathways, treatment regimens, and ultimately, patient outcomes. Misdiagnosis can lead to ineffective treatments, unnecessary side effects, and progressive joint damage.

| Feature | Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) | Osteoarthritis (OA) |

|---|---|---|

| Nature | Autoimmune, systemic inflammatory disease | Degenerative, mechanical disease |

| Primary Pathology | Synovial inflammation (pannus), cartilage/bone erosion | Cartilage breakdown, osteophyte formation, subchondral sclerosis |

| Onset | Insidious, often symmetrical, can be any age (typically 30-50s) | Gradual, often asymmetrical, typically >50 years, often injury-related |

| Joints Affected | Small joints of hands (MCP, PIP), wrists, feet (MTP), knees, shoulders, cervical spine | Weight-bearing joints (knees, hips, spine), hands (DIP, CMC), feet (MTP) |

| Symmetry | Often symmetrical (e.g., both hands) | Often asymmetrical (e.g., one knee) |

| Morning Stiffness | Prolonged (>30 minutes, often hours), improves with activity | Brief (<30 minutes), improves quickly with activity |

| Pain Pattern | Worse at rest, improves with activity, often worse in morning | Worse with activity/weight-bearing, improves with rest, "gelling" after inactivity |

| Inflammation | Significant, systemic (heat, redness, swelling) | Localized, mild, mechanical |

| Systemic Symptoms | Common: fatigue, fever, weight loss, rheumatoid nodules, organ involvement | Absent |

| Blood Tests | Often positive RF, anti-CCP, elevated ESR/CRP | Typically normal; used to rule out RA |

| X-ray Findings | Joint space narrowing, bone erosions, juxta-articular osteopenia (bone thinning near joint) | Joint space narrowing, osteophytes, subchondral sclerosis |

| Treatment Goal | Suppress immune system, halt disease progression, prevent damage | Manage pain, improve function, slow progression |

| Primary Medications | DMARDs (methotrexate, biologics), corticosteroids, NSAIDs | Acetaminophen, NSAIDs, topical agents, injections |

| Prognosis | Progressive, can cause severe disability, but remission possible with treatment | Progressive, manageable, joint replacement common in severe cases |

Why the Distinction Matters:

- Treatment Effectiveness: Giving a patient with RA only pain relievers (as one might for OA) would allow the immune system to continue its destructive assault, leading to irreversible joint damage and disability. Conversely, treating OA with powerful immunosuppressants meant for RA would expose the patient to unnecessary risks without addressing the core mechanical issue.

- Disease Progression: RA, if left untreated, can rapidly progress to severe joint deformities, loss of function, and even shortened lifespan due to systemic complications. OA progresses more slowly, and while it can be severely debilitating, it does not typically affect other organ systems or overall lifespan in the same way.

- Prognosis and Expectations: Understanding the specific diagnosis allows patients to have realistic expectations about their disease course, potential treatments, and long-term outlook. It empowers them to actively participate in their care plan.

Chapter 5: Beyond Diagnosis – Living with Chronic Joint Pain

Regardless of whether the diagnosis is RA or OA, living with chronic joint pain presents significant challenges. It impacts not only physical mobility but also emotional well-being, social interactions, and professional life. However, understanding the specific diagnosis is the first, most crucial step towards effective management and maintaining a fulfilling life.

The Multidisciplinary Approach:

Managing chronic arthritis, whether RA or OA, often requires a team effort:

- Rheumatologist: The primary specialist for RA, and often consulted for OA to rule out inflammatory causes.

- Primary Care Physician: Manages overall health and coordinates care.

- Physical Therapist: Designs exercise programs to improve strength, flexibility, and range of motion.

- Occupational Therapist: Helps patients adapt daily tasks, suggests assistive devices, and teaches joint-protective techniques.

- Pain Management Specialist: For complex or intractable pain.

- Surgeon (Orthopedic): For joint replacement or other corrective surgeries.

- Psychologist/Counselor: To address the emotional toll of chronic pain, depression, and anxiety.

Empowerment Through Education and Self-Management:

Knowledge is power. Patients who understand their condition are better equipped to:

- Adhere to Treatment Plans: Recognizing the "why" behind medications and therapies.

- Make Informed Lifestyle Choices: For RA, avoiding triggers like smoking; for OA, managing weight and engaging in appropriate exercise.

- Advocate for Themselves: Asking informed questions, seeking second opinions, and communicating effectively with their healthcare team.

- Cope with Flares and Setbacks: Understanding that chronic conditions have ups and downs, and having strategies in place for difficult periods.

The Future Horizon:

Research continues to advance on both fronts. For RA, the focus is on more targeted biologics, personalized medicine based on genetic profiles, and even strategies for preventing the disease in high-risk individuals. For OA, breakthroughs are sought in regenerative medicine, such as stem cell therapies or growth factors that could potentially repair or regenerate damaged cartilage, shifting the narrative from just managing symptoms to truly restoring joint health.

Conclusion: Embracing Clarity for a Better Tomorrow

The initial murmur of joint pain can be a confusing, even frightening experience. But by distinguishing between the autoimmune roar of Rheumatoid Arthritis and the degenerative whisper of Osteoarthritis, we gain invaluable clarity. This understanding is not merely academic; it is the cornerstone of accurate diagnosis, effective treatment, and ultimately, a path toward reclaiming quality of life.

For Sarah, the journey with RA will involve meticulously managing her immune system, diligently adhering to medications that keep the systemic inflammation at bay, and working closely with her rheumatologist to prevent joint damage. For Mark, the path with OA will focus on protecting his joints from further mechanical stress, strengthening supporting muscles, and potentially considering interventions that alleviate pain and improve mobility as his cartilage continues its slow decline.

Both journeys are challenging, but neither has to be undertaken in darkness. With the right knowledge, the right healthcare team, and a proactive approach to self-management, individuals like Sarah and Mark can navigate the complexities of their conditions, finding solace in understanding and empowerment in action. The whispers and roars of their joints will always be a part of their story, but with clarity, they can learn to listen, respond, and live lives that are rich, active, and as free from pain as possible.