The Young Person’s Guide to Gout: It’s Not Just an Old Man’s Disease

The collective imagination often paints a specific picture of gout: a portly, red-faced gentleman of advanced years, clutching his throbbing, bandaged foot, a half-eaten steak and a goblet of wine nearby. This caricature, born from centuries of observation and perpetuated by popular culture, is not only incomplete but dangerously misleading. It’s a story rooted in historical truth, yet entirely divorced from the contemporary reality of a disease that increasingly afflicts younger individuals, transcending age, gender, and socio-economic lines. This article seeks to dismantle that antiquated narrative, offering a comprehensive, nuanced exploration of gout for the knowledgeable reader, and importantly, telling the story of why this ancient scourge is far from an old man’s exclusive burden.

The Genesis of a Stereotype: A Historical Echo

To understand the modern misconception, one must first acknowledge its historical foundation. Gout, derived from the Latin "gutta" meaning "a drop" (referring to the belief that a noxious humor dropped into the joints), has been recognized since antiquity. Hippocrates described it as "the unwalkable disease," noting its prevalence in men after puberty and its rarity in women before menopause. Throughout the Middle Ages and into the Enlightenment, gout became inextricably linked with royalty, wealth, and excess. Figures like Henry VIII, Louis XIV, and Benjamin Franklin were famous sufferers, their maladies often attributed to lives of indulgence – rich foods, copious alcohol, and sedentary habits. This "disease of kings" narrative, while accurate for its time given the dietary patterns of the affluent, solidified the image of gout as a self-inflicted ailment of the privileged, and crucially, the elderly.

However, the world has changed dramatically. Diets have diversified, lifestyles have shifted, and the prevalence of certain risk factors has become far more widespread, democratizing gout in a way that Hippocrates could never have foreseen. The story of gout is no longer confined to the elite; it has become a pervasive chapter in the ongoing saga of metabolic health, affecting a broader demographic than ever before.

Beyond the Caricature: Unpacking the Pathophysiology for the Knowledgeable

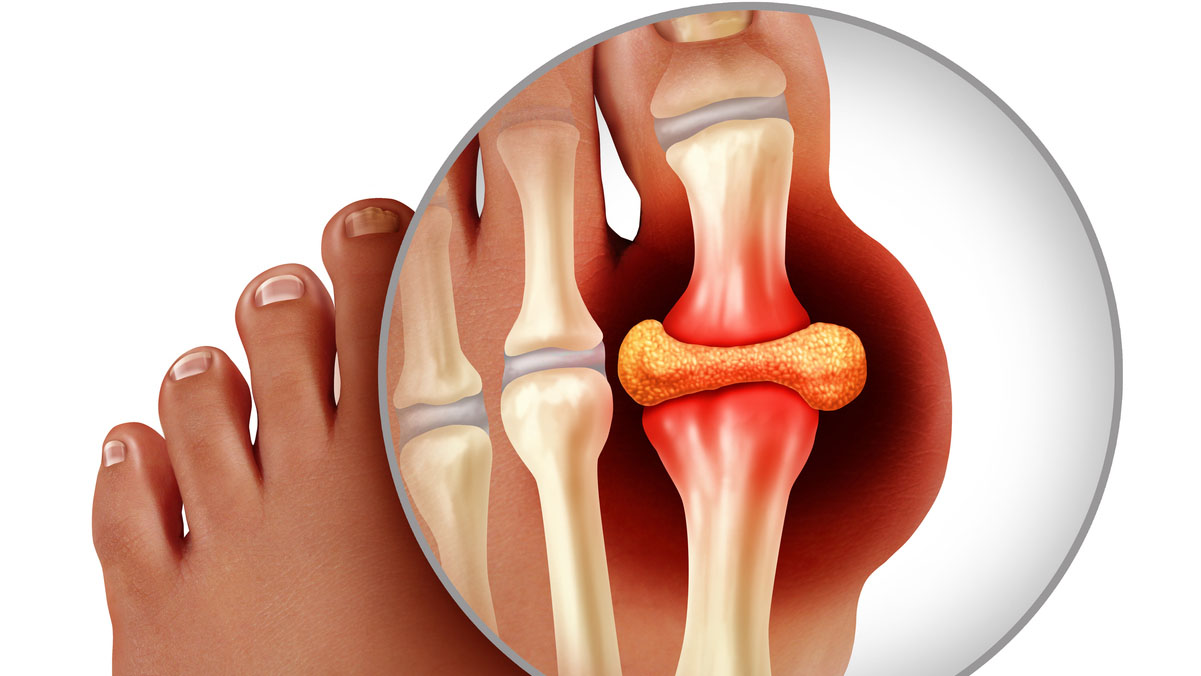

To truly appreciate the contemporary landscape of gout, we must delve into its intricate pathophysiology. Gout is a crystal deposition disease, specifically an inflammatory arthropathy caused by the deposition of monosodium urate (MSU) crystals in joints and soft tissues. This deposition is a direct consequence of sustained hyperuricemia – an abnormally high concentration of uric acid in the blood.

Uric acid is the end-product of purine metabolism. Purines are nitrogenous bases found in DNA and RNA, and are abundant in many foods (e.g., red meat, seafood, organ meats) as well as being synthesized endogenously. Normally, uric acid is dissolved in the blood and efficiently excreted by the kidneys (approximately two-thirds) and the gut (one-third). Hyperuricemia arises when there is either an overproduction of uric acid or, more commonly, an underexcretion of uric acid.

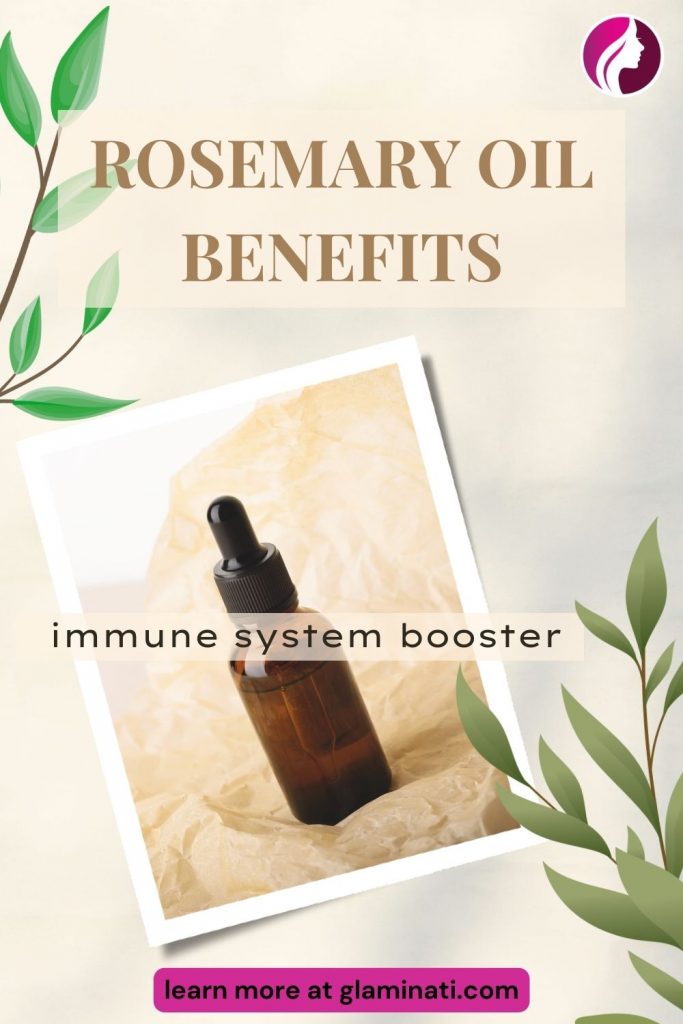

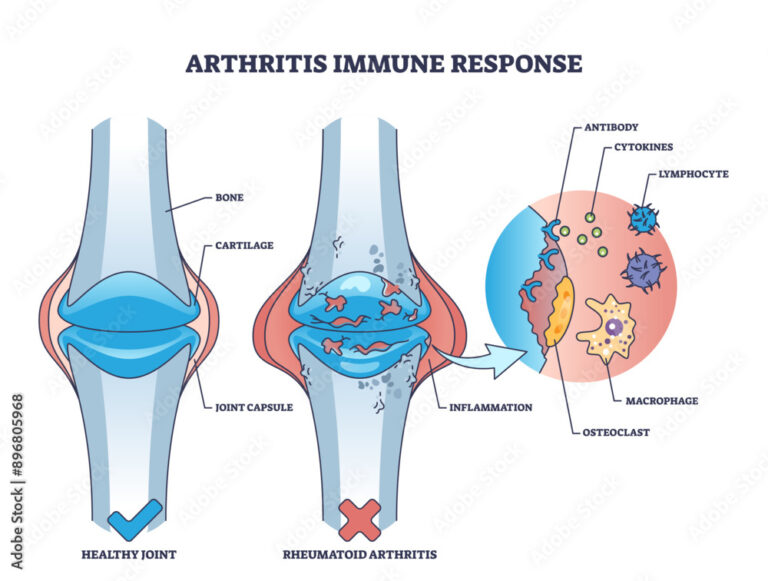

The journey from hyperuricemia to an acute gout attack is a complex immunological ballet. When serum uric acid levels exceed its saturation point (typically >6.8 mg/dL or 400 µmol/L), MSU crystals can form. These needle-shaped crystals, initially dormant, can be shed into the synovial fluid, where they are recognized as "danger signals" by the innate immune system. Macrophages and other immune cells attempt to phagocytose these crystals. Within these cells, the MSU crystals activate the NOD-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, a multiprotein intracellular complex. This activation triggers a cascade of events, leading to the proteolytic cleavage of pro-interleukin-1β (pro-IL-1β) into its active form, IL-1β.

IL-1β is a potent pro-inflammatory cytokine that orchestrates the severe inflammatory response characteristic of an acute gout attack. It recruits neutrophils, promotes vasodilation, and induces the release of other inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α, IL-6, and prostaglandins, culminating in the excruciating pain, swelling, redness, and heat that define a gout flare. The acute attack eventually subsides, often due to natural resolution mechanisms and the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines, but the underlying hyperuricemia persists, setting the stage for future attacks and chronic complications.

The Genetic Blueprint: Predisposition Beyond Lifestyle

While lifestyle factors often grab headlines, genetics play a significant, often underappreciated, role in an individual’s propensity for hyperuricemia and gout. Far from being a mere consequence of overindulgence, genetic polymorphisms can profoundly influence uric acid homeostasis.

Several genes have been identified as key players in uric acid transport and metabolism:

- SLC2A9 (GLUT9): This gene encodes a facilitative glucose transporter family member that is highly expressed in the kidney and liver. Polymorphisms in SLC2A9 are strongly associated with serum uric acid levels, influencing both reabsorption and excretion.

- ABCG2 (BCRP): This gene encodes an ATP-binding cassette transporter involved in the efflux of various substrates, including uric acid, from the body. Variants in ABCG2 are associated with reduced renal and intestinal uric acid excretion, contributing to hyperuricemia.

- SLC22A12 (URAT1): This gene encodes a urate transporter primarily expressed in the renal tubules, responsible for the reabsorption of uric acid from the glomerular filtrate back into the bloodstream. Polymorphisms can alter its function, affecting uric acid retention.

- Other genes: More recently, genes involved in inflammation (e.g., NLRP3 itself) and purine metabolism have also been implicated, suggesting a multifactorial genetic predisposition.

For younger individuals, a strong family history of gout should raise a red flag. These genetic predispositions mean that even with a relatively "healthy" lifestyle, some individuals may have a higher baseline uric acid level, making them more susceptible to developing gout earlier in life when confronted with even moderate environmental triggers. This is a crucial part of the story often overlooked by the "old man’s disease" stereotype.

The Modern Pandora’s Box: Risk Factors in the Young

The narrative of gout as an old man’s disease crumbles under the weight of contemporary risk factors, many of which are increasingly prevalent in younger populations:

- Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity: This cluster of conditions (abdominal obesity, high blood pressure, high blood sugar, high triglycerides, low HDL cholesterol) is a powerful driver of hyperuricemia. Obesity, particularly visceral adiposity, leads to increased uric acid production and decreased renal excretion. The global epidemic of obesity and metabolic syndrome means that millions of younger individuals are walking pathways to hyperuricemia.

- Hypertension and Renal Disease: Both conditions are intimately linked with gout. Hypertension can impair renal uric acid excretion, and conversely, hyperuricemia may contribute to the development and progression of hypertension and chronic kidney disease. Younger patients presenting with early-onset hypertension should be screened for hyperuricemia.

- Dietary Shifts: The Fructose Connection: While traditional purine-rich foods are still relevant, the dramatic increase in consumption of high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS) and other sugar-sweetened beverages is a significant modern dietary culprit. Fructose metabolism rapidly depletes ATP, leading to an accumulation of AMP, which is then degraded into uric acid. Furthermore, fructose can decrease renal uric acid excretion. This dietary pattern is unfortunately common across all age groups, including children and young adults.

- Alcohol Consumption: While any alcohol can exacerbate gout, beer and spirits are particularly problematic due to their purine content (beer) and their ability to increase uric acid production and decrease renal excretion (all types). Binge drinking patterns prevalent in younger demographics can trigger acute flares.

- Medications: Certain medications commonly prescribed for younger individuals or those with chronic conditions can induce hyperuricemia:

- Diuretics (thiazide and loop): Reduce renal uric acid excretion.

- Low-dose Aspirin: Can inhibit uric acid excretion at lower doses.

- Cyclosporine and Tacrolimus: Immunosuppressants used in transplant patients or for autoimmune diseases, significantly impair renal uric acid excretion.

- Pyrazinamide: An anti-tuberculosis drug.

- Chemotherapeutic agents: Can cause tumor lysis syndrome, leading to massive purine release and hyperuricemia.

- Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis: Patients with psoriasis have increased cell turnover, leading to higher purine loads and a higher prevalence of hyperuricemia and gout. Psoriatic arthritis, often affecting younger adults, further intertwines with gout risk.

- Sleep Apnea: Growing evidence suggests a link between obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and hyperuricemia. Intermittent hypoxia in OSA can increase ATP degradation and subsequent uric acid production. OSA is not exclusive to older individuals; it affects many younger, overweight individuals.

- Trauma and Surgery: Acute physical stress, trauma, or surgery can precipitate a gout attack, even in individuals with previously undiagnosed hyperuricemia, regardless of age.

These factors demonstrate that the traditional "old man’s" narrative is not only outdated but actively hinders proper diagnosis and management in a population that is increasingly vulnerable.

Stories from the Front Lines: The Young Person’s Gout Journey

To illustrate the human impact of this evolving landscape, let us consider a few fictionalized, yet composite, stories that echo real-life experiences:

Liam, The Athlete (Age 28): Liam had always been active. A keen amateur footballer, he lived for the weekend games. One Saturday morning, after a particularly intense match and a celebratory round of beers, he woke to an unimaginable pain in his right big toe. It was swollen, red, and exquisitely tender. He dismissed it as a sprain, a minor injury from the pitch. Over the next few months, the attacks recurred, each time more severe. His doctor, initially attributing it to "runner’s toe" or a minor sports injury, finally ordered a uric acid test after Liam insisted something was profoundly wrong. The result: 9.2 mg/dL. Liam was shocked. "Gout? Isn’t that what old men get from eating too much steak?" The diagnosis shattered his self-image as a healthy, fit young man. He faced not only physical pain but also a deep sense of injustice and self-blame, compounded by the dismissive attitudes of some friends who joked about his "rich man’s disease." Liam’s story highlights misdiagnosis, the psychological toll, and the challenge of reconciling a chronic metabolic disease with a young, active identity.

Sarah, The Student (Age 24): Sarah was a bright, driven graduate student, burning the midnight oil, fueling herself with instant noodles, energy drinks, and the occasional fast-food indulgence. She had always been a bit overweight, a fact she attributed to stress and her demanding academic schedule. Her blood pressure was borderline high, but she was too busy to address it seriously. One morning, the pain in her ankle was so intense she couldn’t walk. Her campus clinic doctor, a young resident, initially suspected an infection or a severe sprain. It was only after a week of ineffective antibiotics and increasing pain that an orthopedic consultation and subsequent joint fluid aspiration confirmed MSU crystals. Sarah’s uric acid level was elevated, and her family history revealed her paternal grandfather had severe gout. Her story underscores the role of modern dietary habits, stress, undiagnosed metabolic comorbidities, and genetic predisposition converging to trigger early-onset gout in a demographic far removed from the traditional stereotype.

David, The Dad (Age 35): David was a busy father of two, working long hours in a sedentary office job. He enjoyed craft beers on the weekends and struggled with his weight. He’d had a few "mystery" joint pains over the years, often in his knees or hands, which he’d written off as general aches and pains of getting older. When he developed a persistent, debilitating pain and swelling in his elbow, it was unlike anything he’d experienced before. His general practitioner initially suspected bursitis. It was only when a rheumatologist, noting his multiple tender joints, ordered a dual-energy CT (DECT) scan that the extent of his disease became apparent: multiple tophi, small deposits of MSU crystals, were visible around his joints, a clear sign of chronic, untreated gout. David’s case illustrates the insidious progression of hyperuricemia, the potential for polyarticular involvement beyond the big toe, and the critical importance of early diagnosis and proactive management to prevent irreversible joint damage, even in relatively young individuals.

These stories, while distinct, share a common thread: the shock, the struggle for diagnosis, the stigma, and the profound impact on quality of life, all because a pervasive stereotype obscures the true nature of gout.

Diagnosis and Management: A Proactive Approach for All Ages

The diagnostic criteria for gout remain consistent, regardless of age. The gold standard for confirming an acute attack is the identification of negatively birefringent, needle-shaped MSU crystals within synovial fluid aspirated from the affected joint under polarized light microscopy. Other diagnostic clues include the characteristic clinical presentation (rapidly developing monoarticular arthritis, often nocturnal onset, extreme pain, redness, swelling), elevated serum uric acid (though this can be normal during an acute attack), and imaging findings (e.g., "double contour sign" on ultrasound, erosions, and tophi on radiography or DECT).

Management strategies also follow established guidelines, but with a renewed emphasis on early and sustained intervention, particularly in younger patients who have more years to live with the potential complications of untreated disease:

- Treating the Acute Attack: The primary goal is rapid pain and inflammation relief.

- NSAIDs: (e.g., naproxen, indomethacin) are first-line, if not contraindicated.

- Colchicine: Most effective when initiated within 36 hours of symptom onset.

- Corticosteroids: Oral or intra-articular, particularly useful when NSAIDs or colchicine are contraindicated or ineffective.

- Urate-Lowering Therapy (ULT): This is the cornerstone of long-term gout management, aiming to reduce serum uric acid levels below the saturation point (typically <6 mg/dL or 360 µmol/L, or <5 mg/dL for those with severe disease or tophi) to dissolve existing crystals and prevent new ones.

- Xanthine Oxidase Inhibitors (XOIs):

- Allopurinol: The most commonly prescribed ULT, reducing uric acid production. Dosing must be carefully titrated, especially in patients with renal impairment, and vigilance for hypersensitivity reactions (e.g., DRESS syndrome, particularly in those with HLA-B*58:01 allele) is crucial.

- Febuxostat: A non-purine selective XOI, useful for patients intolerant to allopurinol or with severe renal impairment.

- Uricosurics:

- Probenecid: Increases renal excretion of uric acid. Requires good renal function and careful hydration.

- Pegloticase: A pegylated uricase enzyme, administered intravenously, that metabolizes uric acid into allantoin (a more soluble compound). Reserved for severe, refractory, tophaceous gout.

- Xanthine Oxidase Inhibitors (XOIs):

- Lifestyle Modifications: While ULT is essential, lifestyle changes complement treatment:

- Weight management: Reducing obesity improves uric acid excretion.

- Dietary moderation: Limiting purine-rich foods, high-fructose corn syrup, and excessive alcohol, particularly beer and spirits.

- Hydration: Adequate water intake helps uric acid excretion.

- Management of comorbidities: Aggressive treatment of hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia.

For younger patients, the impetus for aggressive management is even greater. Untreated or poorly controlled gout can lead to chronic pain, irreversible joint damage (gouty arthritis), tophi formation (disfiguring deposits that can impair function), kidney stones, and an increased risk of cardiovascular events. A proactive approach means not only treating flares but committing to long-term ULT to prevent disease progression and preserve joint function for decades to come.

The Broader Impact: Psychological and Socioeconomic Burden

The "old man’s disease" stereotype carries significant psychological and socioeconomic burdens, particularly for younger individuals. Imagine being in your twenties or thirties, trying to build a career, start a family, or maintain an active social life, only to be struck down by excruciating pain, often dismissed as a self-inflicted consequence of indulgence.

- Stigma and Shame: The association with gluttony and alcoholism leads to self-blame and reluctance to seek medical help, or to disclose the diagnosis to peers or employers.

- Misdiagnosis and Delayed Treatment: As seen in Liam’s story, healthcare providers, influenced by the stereotype, may initially overlook gout in younger patients, leading to prolonged suffering and disease progression.

- Impact on Quality of Life: Chronic pain, recurrent flares, and joint damage can significantly impair daily activities, work productivity, social engagement, and mental health, contributing to anxiety and depression.

- Economic Cost: Lost workdays, medical expenses, and potential disability translate into substantial economic costs for both individuals and healthcare systems.

Challenging the stereotype is not merely an academic exercise; it is a critical step towards destigmatization, improved patient outcomes, and a more equitable approach to chronic disease management.

The Future: Precision, Prevention, and Public Awareness

The story of gout is still being written. Advances in genomics and personalized medicine hold promise for identifying individuals at high risk earlier, allowing for targeted preventive strategies. New therapeutic agents, exploring novel targets in the inflammatory cascade or uric acid transport, are continually being investigated.

Crucially, the future demands a concerted effort in public health awareness. Educational campaigns must actively dismantle the "old man’s disease" myth, highlighting the modern risk factors and the importance of early diagnosis and consistent management for all demographics. Healthcare providers, particularly primary care physicians, need ongoing education to recognize gout in its diverse presentations and in younger patients.

Conclusion: A New Chapter for an Ancient Foe

The story of gout is a compelling narrative of human interaction with disease, from ancient observations to modern molecular insights. It is a tale of shifting demographics, evolving risk factors, and the persistent challenge of societal stereotypes. The "Young Person’s Guide to Gout" is not just a medical treatise; it’s a call to action. It urges us to discard the antiquated image of the gouty old man and embrace a more accurate, inclusive understanding of a complex metabolic disease.

Gout is a formidable foe, capable of inflicting severe pain and long-term disability. But it is also a treatable disease, with effective therapies capable of controlling hyperuricemia and preventing its devastating consequences. For the younger generation, understanding that gout is not a distant threat but a present possibility is paramount. It is time to rewrite the narrative, to move beyond the caricature, and to ensure that no young person needlessly suffers from a condition that is often preventable and always manageable. The story of gout, for too long defined by myth and stereotype, deserves a new, enlightened chapter – one of awareness, early intervention, and unwavering commitment to patient well-being, irrespective of age.