Understanding Remission: Is It Possible to Halt Rheumatoid Arthritis Progression?

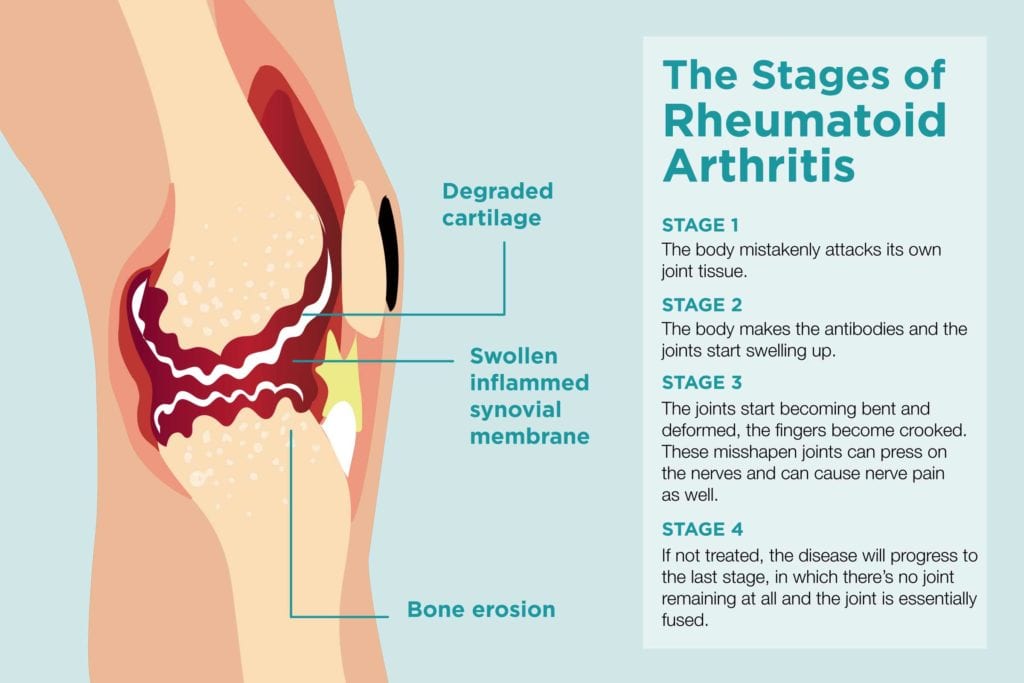

For decades, the diagnosis of Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) carried a grim prognosis, often painted with strokes of inevitable joint destruction, crippling deformities, and a life increasingly circumscribed by pain and disability. Patients faced a future where the relentless march of inflammation eroded cartilage and bone, fused joints into unyielding rigidity, and systematically chipped away at their quality of life. The very word "arthritis" conjured images of elderly hands gnarled and twisted, a testament to a disease that seemed to defy control.

But a silent revolution has been unfolding in the world of rheumatology, a seismic shift in understanding, diagnosis, and treatment that has fundamentally altered the narrative of RA. Today, the conversation is no longer solely about managing symptoms; it’s about achieving a state once thought to be an impossible dream: remission. The question that now echoes through clinics and research labs alike is not if remission is possible, but how to achieve it reliably, sustain it, and, critically, whether it truly halts the insidious progression of this chronic autoimmune disease.

This article delves into the multifaceted concept of remission in Rheumatoid Arthritis, charting its evolving definitions, exploring the scientific breakthroughs that have made it a tangible goal, dissecting the challenges that remain, and looking towards a future where the halting of RA progression might become the expected outcome, rather than a hopeful anomaly. Our journey will reveal that remission is not a monolithic state but a spectrum, with profound implications for how we understand and combat this complex illness.

The Shifting Sands of Definition: What Exactly is Remission?

The concept of remission in RA has been a moving target, evolving significantly as our understanding of the disease deepens and our diagnostic and therapeutic tools become more sophisticated. What was once considered "remission" a few decades ago might barely qualify as low disease activity today. This evolution reflects a growing appreciation for the subtle yet persistent nature of inflammation in RA, even in the absence of overt symptoms.

Early Definitions: Clinical Remission as the Benchmark

Historically, remission was largely defined by clinical criteria, focusing on the absence or significant reduction of obvious symptoms. The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for clinical remission, established in the 1980s, required patients to meet several conditions for at least six consecutive months:

- No tender joints

- No swollen joints

- No morning stiffness

- No fatigue

- No pain

- No elevation of erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), a marker of inflammation.

While these criteria offered a useful initial framework, they were often difficult to meet fully and didn’t always correlate with the underlying biological activity of the disease. A patient might report feeling well, but subtle inflammation could still be simmering beneath the surface, silently chipping away at their joints.

Composite Disease Activity Scores: Towards Objectivity

The advent of composite disease activity scores marked a significant step forward in standardizing the assessment of RA activity. These scores combine various measures to provide a more holistic picture of a patient’s condition:

-

DAS28 (Disease Activity Score in 28 joints): This widely used index incorporates the number of tender and swollen joints (out of 28 specific joints), the patient’s global assessment of disease activity (on a visual analogue scale), and an inflammatory marker (either ESR or C-reactive protein – CRP). A DAS28 score below 2.6 is generally considered to be in remission.

-

SDAI (Simplified Disease Activity Index) and CDAI (Clinical Disease Activity Index): These indices are similar to DAS28 but simplify calculations. SDAI includes the number of tender and swollen joints, patient global assessment, physician global assessment, and CRP. CDAI omits CRP, making it entirely clinical and allowing for immediate assessment. SDAI remission is typically defined as ≤ 3.3, and CDAI remission as ≤ 2.8.

These composite scores offered a more objective and reproducible way to track disease activity and guide treatment decisions, paving the way for the "treat-to-target" strategy.

ACR/EULAR Remission Criteria: The Gold Standard for Clinical Trials

In 2011, the ACR and the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) collaborated to establish new, stricter criteria for remission, primarily for use in clinical trials but also increasingly adopted in practice. These criteria recognize two paths to remission:

-

Boolean Remission: This requires patients to meet all of the following simultaneously:

- Tender joint count ≤ 1

- Swollen joint count ≤ 1

- C-reactive protein (CRP) ≤ 1 mg/dL

- Patient global assessment of disease activity ≤ 1 (on a 0-10 scale)

-

SDAI Remission: An SDAI score ≤ 3.3.

These criteria are more stringent than the original DAS28 definition, reflecting a deeper commitment to eradicating even minimal disease activity. Achieving remission by these criteria is considered a more robust indicator of disease control.

Beyond Clinical: Imaging and Molecular Remission

However, even with these rigorous clinical and composite score definitions, a crucial realization emerged: patients could meet all criteria for clinical remission yet still harbor subclinical inflammation. This "invisible" inflammation, detectable only through advanced imaging or molecular analyses, can continue to cause damage, albeit at a slower pace. This led to the concept of "deeper remission."

-

Imaging Remission:

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): MRI can detect subtle synovitis (inflammation of the joint lining), bone marrow edema (an early indicator of bone erosion), and even small erosions not visible on X-rays. Imaging remission implies the absence of these inflammatory signs on MRI.

- Ultrasound (US): High-resolution ultrasound can also detect synovitis, power Doppler signals (indicating active blood flow within inflamed tissue), and early erosions. Ultrasound remission suggests the absence of these inflammatory markers.

The presence of subclinical synovitis on MRI or US in patients who are in clinical remission is a strong predictor of future flares and radiographic progression, underscoring the importance of this deeper level of assessment.

-

Molecular and Histological Remission: This represents the deepest level of disease control, involving analysis of synovial tissue (from joint biopsies) or blood samples for inflammatory markers at a cellular and genetic level. It aims to identify the absence of inflammatory cells, cytokines, and gene expression patterns characteristic of active RA. This level of remission is currently primarily a research tool but holds the promise of truly personalized medicine, guiding treatment withdrawal and preventing relapse.

The journey through these definitions illustrates a profound shift: from merely silencing symptoms to actively extinguishing the underlying inflammatory fire. The goal is no longer just "feeling better," but achieving a state where the disease is truly quiescent, biologically and pathologically.

Why Remission Matters: Beyond Symptom Relief

Achieving remission in RA is not merely about numerical targets or clinical scores; it has profound, life-altering implications for patients. The benefits extend far beyond the immediate relief from pain and swelling, touching every aspect of their health and well-being.

1. Halting Structural Damage: This is perhaps the most critical benefit. Active RA causes progressive joint damage, leading to erosions, cartilage loss, and ultimately, joint deformities and functional impairment. Studies consistently show that achieving and maintaining remission, particularly early in the disease course, significantly reduces or even completely halts radiographic progression (the worsening of joint damage visible on X-rays). Deeper forms of remission, as detected by MRI or ultrasound, are even more effective at preventing this insidious destruction. For a disease historically defined by its erosive potential, this represents a monumental victory.

2. Preserving Physical Function and Quality of Life: By preventing joint damage and controlling inflammation, remission allows patients to maintain their physical function, perform daily activities, and participate in work and social life without the limitations imposed by active disease. This translates directly into a dramatically improved quality of life, allowing individuals to live fuller, more independent lives. The psychological burden of a chronic, progressively disabling illness is also significantly lifted.

3. Reducing Systemic Complications: RA is not just a disease of the joints; it’s a systemic inflammatory disorder. Chronic inflammation increases the risk of various comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease (atherosclerosis, heart attack, stroke), interstitial lung disease, osteoporosis, and certain malignancies (e.g., lymphoma). By suppressing systemic inflammation, achieving remission can mitigate these risks, leading to better overall health outcomes and potentially increased life expectancy.

4. The Potential for Treatment De-escalation or Withdrawal: While often approached with caution, achieving sustained, deep remission may open the door to carefully considered treatment de-escalation, such as reducing the dose of biologics or even attempting drug-free remission in select patients. This can reduce the financial burden, minimize side effects, and improve patient convenience, though it must be done under strict medical supervision due to the risk of relapse.

In essence, remission transforms the trajectory of RA from one of inevitable decline to one of potential stability and preserved function. It is the ultimate goal of modern RA management, underpinning the entire therapeutic strategy.

The Journey to Remission: A Multi-Pronged Approach

The paradigm shift towards achieving remission in RA has been fueled by a combination of earlier diagnosis, a deeper understanding of pathophysiology, and the development of powerful new therapies. The path to remission is rarely linear, often requiring a dynamic and personalized approach.

1. Early Diagnosis: The "Window of Opportunity"

One of the most critical factors in achieving sustained remission is early diagnosis and intervention. Research has unequivocally demonstrated the existence of a "window of opportunity" – a period, typically within the first few months after symptom onset, during which aggressive treatment is most likely to induce remission and prevent irreversible joint damage. During this early phase, the immune system’s dysregulation might be more amenable to correction, and the inflammatory cascade less entrenched.

Rheumatologists are increasingly focused on identifying RA in its nascent stages, utilizing advanced diagnostic criteria, autoantibody testing (e.g., rheumatoid factor, anti-citrullinated protein antibodies – ACPA), and even imaging like MRI to detect subtle inflammation before overt symptoms or erosions appear.

2. The Treat-to-Target (T2T) Strategy

The T2T strategy is the cornerstone of modern RA management. It involves setting a clear therapeutic target, typically remission or low disease activity, and then systematically adjusting treatment until that target is achieved. This proactive approach contrasts sharply with older methods that often waited for disease progression before escalating therapy.

Key principles of T2T include:

- Shared Decision-Making: Patients and rheumatologists collaboratively set the treatment goal.

- Frequent Monitoring: Disease activity is regularly assessed using composite scores (DAS28, SDAI, CDAI).

- Timely Adjustment: If the target is not met within a specified timeframe (e.g., 3-6 months), treatment is escalated or changed.

This iterative process ensures that patients receive the optimal level of therapy to suppress inflammation effectively.

3. The Modern Pharmacological Arsenal

The development of new drugs has been instrumental in making remission an achievable goal.

-

Conventional Synthetic DMARDs (csDMARDs): Methotrexate remains the cornerstone of RA treatment and is often the first-line therapy. Other csDMARDs like leflunomide, sulfasalazine, and hydroxychloroquine are also used, often in combination. They work by modulating the immune system in various ways. Early and adequate dosing of methotrexate is crucial.

-

Biologic DMARDs (bDMARDs): These revolutionary drugs target specific molecules or cells involved in the inflammatory process. They have transformed the landscape of RA treatment.

- TNF Inhibitors: (e.g., adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, certolizumab, golimumab) Target tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), a key pro-inflammatory cytokine.

- IL-6 Inhibitors: (e.g., tocilizumab, sarilumab) Block the interleukin-6 (IL-6) receptor, another crucial inflammatory cytokine pathway.

- T-cell Costimulation Modulators: (e.g., abatacept) Interfere with the activation of T-lymphocytes, which play a central role in autoimmune responses.

- B-cell Depleters: (e.g., rituximab) Target CD20 on B-lymphocytes, which are involved in antibody production and antigen presentation.

-

Targeted Synthetic DMARDs (tsDMARDs):

- JAK Inhibitors: (e.g., tofacitinib, baricitinib, upadacitinib, filgotinib) These small molecules work intracellularly, blocking the Janus kinase (JAK) signaling pathways, which are critical for the function of many inflammatory cytokines. They offer an oral alternative to injectable biologics.

The strategic use of these agents, often in combination (e.g., methotrexate with a biologic), allows rheumatologists to tailor therapy to individual patient needs and achieve aggressive disease control.

4. Personalized Medicine: The Promise of Precision

While the current therapeutic arsenal is powerful, predicting which patient will respond best to which drug remains a challenge. The future of RA treatment lies in personalized medicine, where treatment decisions are guided by an individual’s unique genetic makeup, biomarker profile, and disease characteristics.

- Biomarkers: Research is ongoing to identify biomarkers (e.g., specific autoantibodies, gene expression patterns, cytokine profiles) that can predict drug response, identify patients at high risk of progression, or indicate deeper levels of remission.

- Genetics: Genetic profiling may eventually help guide drug selection, avoiding ineffective treatments and minimizing side effects.

5. Lifestyle and Adjunctive Therapies: While medications are primary, lifestyle factors play a supportive role.

- Diet: An anti-inflammatory diet (e.g., Mediterranean diet) may help reduce systemic inflammation.

- Exercise: Regular, appropriate exercise helps maintain joint mobility, muscle strength, and overall well-being.

- Smoking Cessation: Smoking is a known risk factor for developing more severe RA and can reduce treatment efficacy.

- Stress Management: Chronic stress can exacerbate autoimmune conditions.

The modern approach to RA is thus a comprehensive one, combining early and aggressive pharmacological intervention with a personalized, treat-to-target strategy, all supported by a holistic view of patient well-being.

The Elusive Goal: Drug-Free Remission

For many patients, the ultimate dream is not just remission, but drug-free remission – a state where the disease remains quiescent without the need for ongoing medication. This represents the closest RA currently comes to a "cure." While tantalizing, it remains an elusive goal for most.

Is Drug-Free Remission Possible?

Yes, for a small subset of patients, drug-free remission is achievable. These individuals manage to withdraw from all RA medications and remain in remission for extended periods. However, this is far from the norm, and the vast majority of patients who attempt drug withdrawal experience a relapse.

Predictors of Successful Withdrawal:

Research has identified several factors that increase the likelihood of achieving sustained drug-free remission:

- Early Diagnosis and Treatment: Patients diagnosed and treated very early in the disease course, especially within the "window of opportunity," are more likely to achieve deep, sustained remission that might allow for withdrawal.

- Sustained Deep Remission: A prolonged period (e.g., 6-12 months or more) of deep, stable remission (ideally by stringent ACR/EULAR criteria, and even better, with no imaging evidence of synovitis) before attempting withdrawal.

- Absence of Erosions: Patients without baseline joint erosions or who have achieved structural remission (no progression of erosions) are better candidates.

- Negative Autoantibodies: Seronegative RA (negative for RF and ACPA) is sometimes associated with a milder disease course and potentially a higher chance of successful withdrawal, though this is not a universal rule.

- Specific Biomarkers: Future research hopes to identify molecular biomarkers that can reliably predict which patients can safely withdraw from medication.

The Risks of Relapse:

The primary concern with attempting drug withdrawal is the high risk of disease flare. Relapses can lead to renewed inflammation, pain, and, critically, accelerated joint damage. While many relapses can be brought back under control by reintroducing medication, repeated flares can erode joint integrity and diminish the overall prognosis. This risk necessitates a highly cautious approach, typically involving:

- Gradual Tapering: Medications are usually tapered slowly, rather than stopped abruptly.

- Close Monitoring: Patients are monitored very frequently after withdrawal for any signs of disease activity.

- Patient Education: Patients must be fully informed about the risks of relapse and the importance of prompt reporting of symptoms.

Current Consensus:

For the vast majority of RA patients, particularly those with established disease and positive autoantibodies, maintaining continuous therapy remains the recommended strategy to prevent disease flares and progressive joint damage. Drug withdrawal is generally only considered in highly selected patients under strict medical supervision, often within the context of clinical trials. While it remains a beacon of hope, it is not yet a realistic expectation for most. The focus remains on achieving and sustaining the deepest possible remission with ongoing therapy.

Navigating the Labyrinth: Challenges and Unanswered Questions

Despite the remarkable progress, the journey to universal, sustained remission for all RA patients is fraught with challenges and unanswered questions.

1. Heterogeneity of RA: Rheumatoid Arthritis is not a single disease but a spectrum of conditions. Patients present with varying genetic predispositions, autoantibody profiles, inflammatory pathways, and clinical manifestations. This heterogeneity means that a "one-size-fits-all" approach to treatment is ineffective. What works for one patient may fail for another, making personalized medicine both a necessity and a significant challenge.

2. The Persistent Gap in Biomarkers: We still lack reliable biomarkers that can definitively predict who will respond to which therapy, who is at highest risk of progression despite clinical remission, or who can safely withdraw from medication. The discovery and validation of such biomarkers are crucial for truly precision medicine.

3. Treatment Non-Response and Side Effects: A significant proportion of patients do not achieve remission with current therapies, even with the most advanced biologics and JAK inhibitors. Furthermore, all potent medications carry the risk of side effects, including infections, cardiovascular events, and malignancies, necessitating careful risk-benefit assessments.

4. The Burden of Disease Activity, Even in "Low": While low disease activity is a vastly better state than high activity, even minimal inflammation can contribute to progressive joint damage, fatigue, and reduced quality of life over the long term. This reinforces the drive for true remission, not just adequate control.

5. The Patient Perspective: Beyond the Numbers: For patients, remission is more than just a score on a chart. It encompasses freedom from pain, restored function, the ability to work, and psychological well-being. Even patients in clinical remission may still experience fatigue, mild pain, or functional limitations that aren’t fully captured by current metrics. Understanding and addressing these residual symptoms is vital.

6. Cost and Access: The advanced therapies that make remission possible are often very expensive, posing significant challenges for healthcare systems and patient access, especially in resource-limited settings.

These challenges highlight that while much has been achieved, the fight against RA is far from over. It calls for continued research, innovative drug development, and a deeper understanding of the disease’s fundamental mechanisms.

The Horizon: Future Directions in Halting Progression

The story of RA remission is one of relentless scientific inquiry and innovation. The future promises even more sophisticated approaches to not only halt progression but perhaps even induce long-term immunological tolerance.

1. Deeper Dive into Personalized Medicine:

- Omics Technologies: Genomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and single-cell RNA sequencing are revealing unprecedented details about the molecular landscape of individual patients’ RA. This data will be critical for identifying precise therapeutic targets and predicting drug response.

- Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning: AI algorithms are being developed to analyze vast datasets of patient information (clinical, genetic, imaging) to identify patterns, predict outcomes, and optimize treatment strategies.

2. Novel Therapeutic Targets:

- Epigenetics: Research into epigenetic modifications (changes in gene expression without altering the DNA sequence) offers new avenues for therapeutic intervention, as these play a role in regulating immune responses.

- Microbiome Modulation: The gut microbiome is increasingly recognized as a key player in autoimmune diseases. Therapies aimed at modulating the gut flora (e.g., probiotics, fecal microbiota transplantation) could become future treatment strategies.

- Targeting Fibroblast-like Synoviocytes (FLS): These cells in the joint lining become highly aggressive and destructive in RA. Therapies that specifically target and reprogram or eliminate pathological FLS could offer a joint-specific approach to halting damage.

3. Immunotolerance Induction: The ultimate "cure" for RA would involve inducing immunological tolerance – retraining the immune system to stop attacking self-tissues without broadly suppressing immunity. This is a highly complex area of research, potentially involving cell-based therapies (e.g., regulatory T-cells), antigen-specific therapies, or even gene therapy approaches. While still largely experimental, it represents the holy grail of autoimmune disease treatment.

4. Advanced Imaging for Precision Monitoring: Continued advancements in imaging techniques will allow for even more sensitive detection of subclinical inflammation and structural damage, providing earlier warnings of disease activity and more precise guidance for treatment adjustments.

5. Prevention: Ultimately, the most impactful future direction lies in understanding the triggers of RA and developing strategies to prevent its onset in genetically susceptible individuals. This involves identifying environmental factors, early biomarkers, and potentially prophylactic interventions.

Conclusion: A New Era of Hope

The narrative of Rheumatoid Arthritis has been irrevocably altered. From a diagnosis that once presaged inevitable decline, it has transformed into a condition where remission is not just a possibility, but a tangible and increasingly achievable goal. The relentless progression of joint damage, once a hallmark of the disease, can now often be halted, and for many, their physical function and quality of life can be preserved.

This profound shift is a testament to decades of scientific endeavor, marked by a deeper understanding of immunology, the development of sophisticated diagnostic tools, and the creation of a powerful arsenal of targeted therapies. The evolving definition of remission itself – from simple clinical criteria to the nuanced detection of subclinical inflammation via imaging and molecular analysis – mirrors this journey of ever-increasing precision and ambition.

While the elusive dream of drug-free remission remains a reality for only a fortunate few, the ability to achieve and sustain deep remission with ongoing therapy represents a monumental triumph. It empowers patients to live lives no longer defined by their illness, offering freedom from pain, preservation of function, and a significant reduction in systemic complications.

Yet, the story is far from over. The heterogeneity of RA, the challenges of non-response, the need for better biomarkers, and the pursuit of truly personalized, curative strategies continue to drive vigorous research. The horizon promises even more revolutionary breakthroughs, hinting at a future where RA might be not only halted but perhaps even prevented or cured.

The journey to understanding and mastering Rheumatoid Arthritis has been long and arduous, but the current era offers unprecedented hope. Remission is no longer a whispered wish but a strategic objective, and with it, the possibility of truly halting the relentless march of this complex disease, restoring health, and reclaiming futures.