Can Cumin Lower Your Cholesterol? The Research Revealed

The Quest for Nature’s Remedies in a Modern Epidemic

In an era defined by scientific breakthroughs and pharmaceutical marvels, humanity’s ancient wisdom often whispers a compelling counter-narrative: that healing might also reside in the bounty of the earth. From the unassuming roots of ginger to the vibrant hues of turmeric, the spice rack has, for millennia, been more than just a culinary repository; it has been a veritable apothecary. Among these potent provisions, a small, unassuming seed, with its distinctive earthy aroma and warm, slightly bitter taste, has quietly garnered increasing attention: cumin.

For centuries, Cuminum cyminum has woven itself into the fabric of cultures, from the sun-drenched cuisines of the Middle East and India to the vibrant kitchens of Mexico. Beyond its role as a flavor enhancer, traditional medicine systems like Ayurveda and Unani have long extolled its virtues, attributing to it properties ranging from digestive aid to anti-inflammatory agent. But as the shadows of modern health epidemics lengthen, particularly the pervasive specter of high cholesterol and cardiovascular disease, a new and pressing question arises: can this ancient spice offer a contemporary solution? Can cumin lower your cholesterol?

This is not a simple query demanding a definitive "yes" or "no." It is a call to embark on a scientific odyssey, a journey through the intricate pathways of human physiology, the rigorous methodologies of clinical research, and the nuanced interpretations of findings. For a knowledgeable audience, the answer lies not in anecdotal whispers, but in the meticulous examination of the research revealed.

Our story begins, as all good stories do, with setting the stage: understanding the protagonist of our health narrative, cholesterol itself, and the formidable challenge it poses.

Chapter 1: The Cholesterol Conundrum – Understanding the Silent Threat

Before we can ask if cumin can impact cholesterol, we must first understand what cholesterol is, why it matters, and how it becomes a threat. Cholesterol is a waxy, fat-like substance essential for life. It’s a fundamental building block for cell membranes, a precursor to vitamin D, and crucial for producing hormones like estrogen and testosterone, and bile acids that aid digestion. Our liver produces all the cholesterol we need, but we also ingest it through certain foods.

The problem isn’t cholesterol itself, but its excess and the way it’s transported in the bloodstream. Cholesterol, being a lipid, cannot travel freely in our water-based blood. It’s packaged into lipoproteins – tiny spheres with a protein shell and a lipid core. The two main types we discuss in relation to heart health are:

- Low-Density Lipoprotein (LDL): Often dubbed "bad" cholesterol. LDL particles carry cholesterol from the liver to cells throughout the body. When there’s too much LDL, it can accumulate in the walls of arteries, forming plaque. This plaque hardens and narrows the arteries, a process called atherosclerosis, which can lead to heart attacks and strokes.

- High-Density Lipoprotein (HDL): Known as "good" cholesterol. HDL particles act like scavengers, picking up excess cholesterol from the arteries and carrying it back to the liver for removal from the body. Higher levels of HDL are generally protective against heart disease.

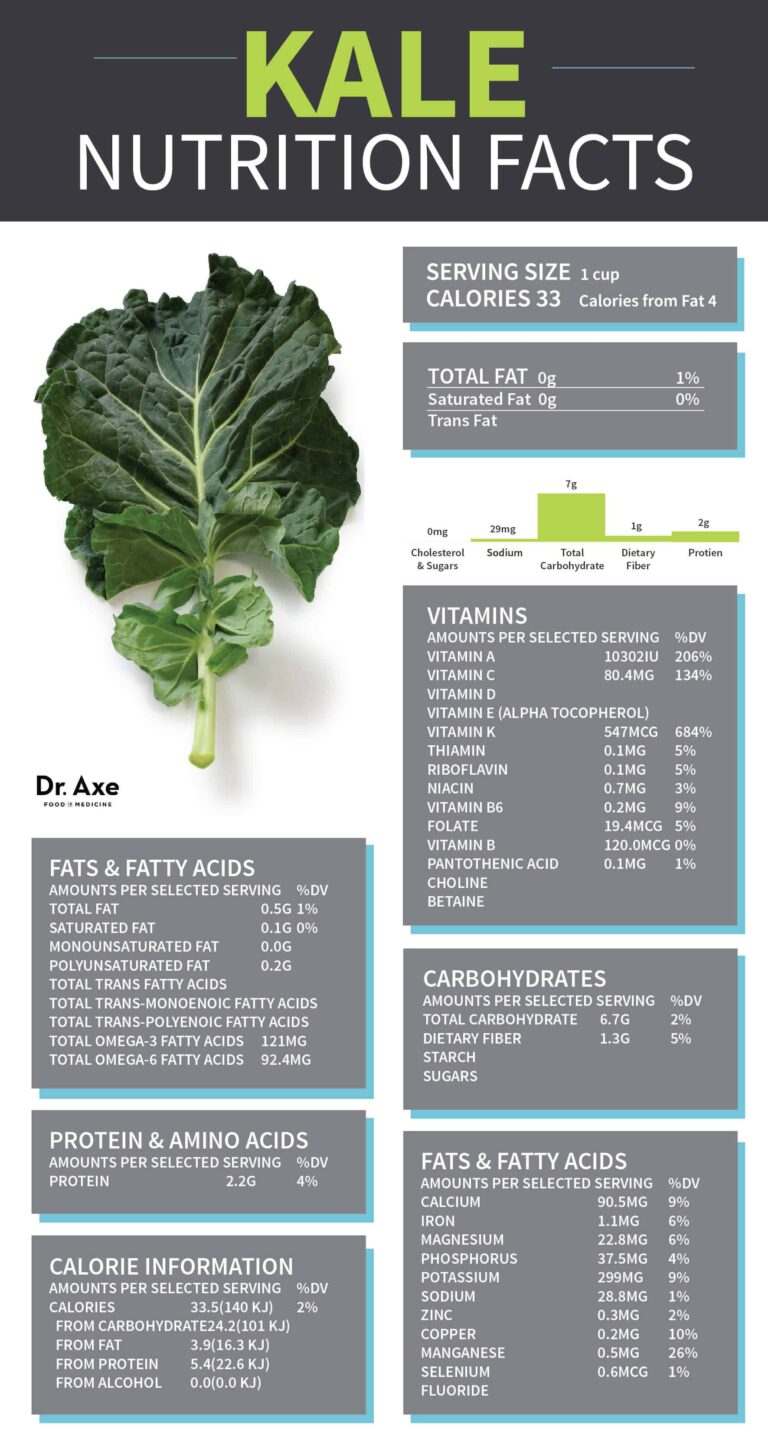

Beyond LDL and HDL, we also consider triglycerides, another type of fat in the blood. High triglycerides, often linked to diets high in refined carbohydrates and sugars, can also increase the risk of heart disease, especially when combined with high LDL and low HDL.

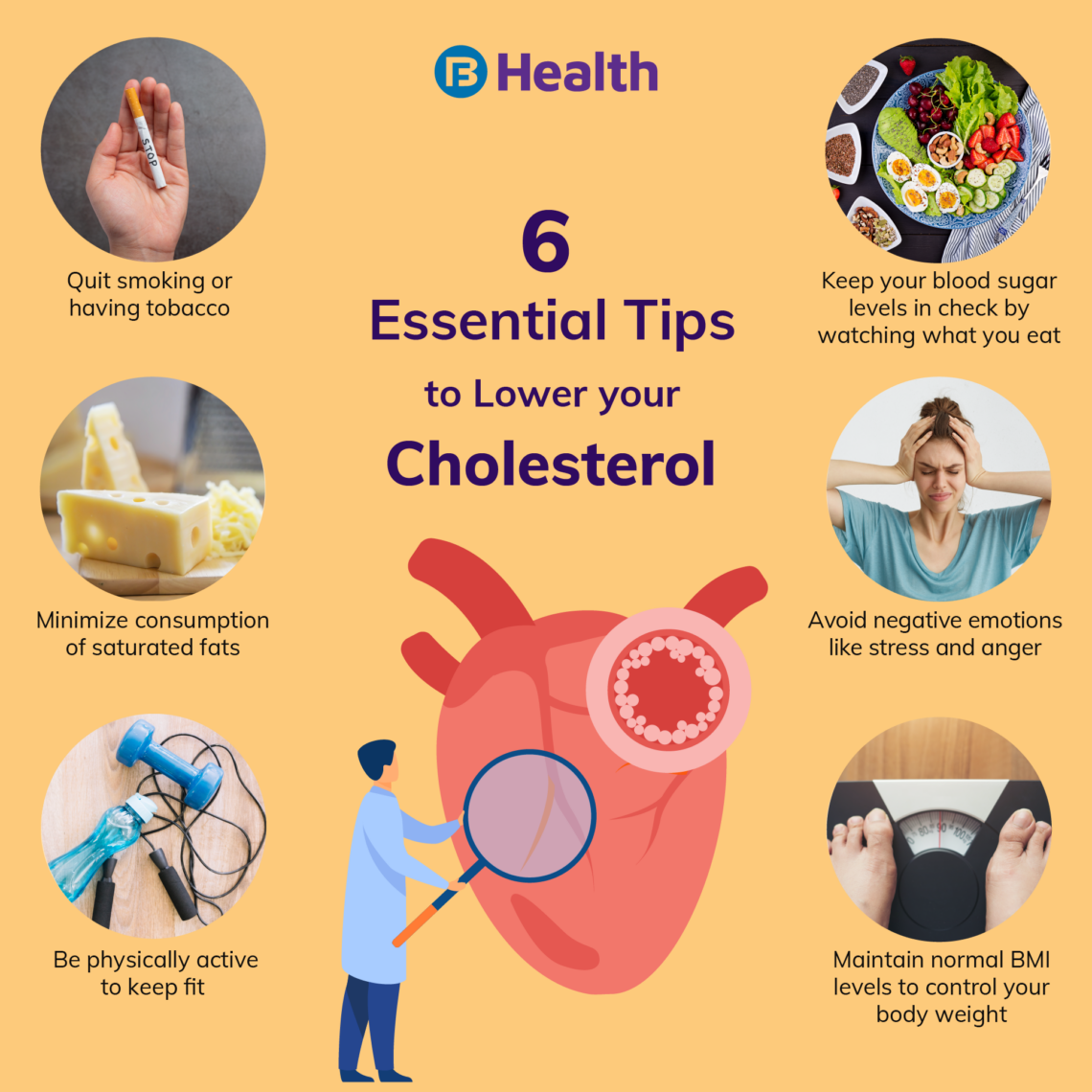

The global burden of high cholesterol is immense. It’s a leading risk factor for cardiovascular diseases, which remain the number one cause of death worldwide. Conventional approaches to managing high cholesterol include lifestyle modifications (dietary changes, exercise, weight management), and pharmacological interventions like statins, which are highly effective but can come with side effects. This context fuels the persistent search for complementary or alternative strategies, prompting a closer look at natural compounds like those found in cumin.

Chapter 2: Cumin – A Spice Beyond Flavor, a History of Healing

Our next step is to truly meet cumin. Cuminum cyminum belongs to the Apiaceae family, making it a cousin to parsley, carrots, and dill. Native to the Middle East, its use dates back thousands of years. Archaeological evidence places cumin in ancient Egypt, where it was not only a culinary staple but also used in mummification rituals. The Romans and Greeks valued it for both food and medicine. By the Middle Ages, it had spread across Europe and Asia, eventually making its way to the Americas with Spanish and Portuguese explorers.

Historically, cumin’s medicinal applications have been diverse:

- Digestive Aid: Perhaps its most celebrated traditional use, cumin seeds were often chewed after meals or brewed into teas to alleviate indigestion, bloating, and flatulence.

- Anti-inflammatory: Traditional healers used cumin for conditions involving inflammation, from joint pain to respiratory issues.

- Antimicrobial: Its essential oils were recognized for their ability to combat certain bacteria and fungi.

- Diuretic: It was believed to promote urination and aid in detoxification.

- Lactogenic: In some cultures, it was given to nursing mothers to stimulate milk production.

These traditional applications hint at a complex phytochemical profile within the tiny seed. Modern science, with its analytical tools, has begun to unravel the constituents responsible for these effects. Cumin is rich in volatile oils, particularly cuminaldehyde, cymene, and gamma-terpinene, which contribute to its characteristic aroma and many of its biological activities. It also contains flavonoids (e.g., luteolin, apigenin), phenolic acids, and a good amount of dietary fiber. It is this intricate symphony of compounds that researchers believe might hold the key to its potential impact on cholesterol.

Chapter 3: The Biochemical Hypothesis – How Cumin Might Work

To understand if cumin can lower cholesterol, we must first explore the plausible biological mechanisms. How could a simple seed influence such a complex metabolic pathway? The scientific community has put forth several hypotheses, drawing from cumin’s known properties and the broader understanding of lipid metabolism:

-

Antioxidant Powerhouse: Oxidative stress plays a critical role in the development of atherosclerosis. When LDL cholesterol becomes oxidized, it becomes particularly harmful, contributing to plaque formation in arteries. Cumin is a rich source of antioxidants – phenolics, flavonoids, and terpenes. These compounds scavenge free radicals, neutralizing reactive oxygen species (ROS) and thereby protecting LDL from oxidation. By reducing oxidative stress, cumin might indirectly mitigate the progression of atherosclerosis.

-

Anti-inflammatory Effects: Chronic low-grade inflammation is now recognized as a key driver in cardiovascular disease. Inflammation contributes to endothelial dysfunction (damage to the inner lining of blood vessels) and promotes plaque instability. Cumin’s anti-inflammatory compounds, such as those found in its essential oils, may modulate inflammatory pathways, reducing the overall inflammatory burden on the cardiovascular system. This could indirectly impact cholesterol’s detrimental effects.

-

Direct Impact on Lipid Metabolism: This is where the mechanisms become more specific to cholesterol regulation.

- Inhibition of HMG-CoA Reductase: Statins, the gold standard for cholesterol lowering, work by inhibiting HMG-CoA reductase, a key enzyme in the liver responsible for cholesterol synthesis. Some in vitro and animal studies have suggested that certain compounds in cumin might exert a similar, albeit milder, inhibitory effect on this enzyme, thereby reducing the liver’s production of cholesterol.

- Increased Bile Acid Excretion: Cholesterol is a precursor to bile acids, which are produced in the liver and secreted into the intestines to aid fat digestion. Dietary fiber, abundantly present in whole cumin seeds, can bind to bile acids in the gut, preventing their reabsorption and promoting their excretion. To replenish the lost bile acids, the liver must draw more cholesterol from the blood, effectively lowering circulating cholesterol levels.

- Modulation of PPARs: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) are a group of nuclear receptor proteins that play crucial roles in regulating gene expression involved in lipid and glucose metabolism. Specifically, PPAR-alpha activation can lead to increased fatty acid oxidation and a reduction in triglyceride levels. Some plant compounds are known to modulate PPAR activity, and cumin’s constituents might interact with these receptors to favorably influence lipid profiles.

- Lipogenesis and Lipolysis Regulation: Cumin may influence the enzymes involved in fat synthesis (lipogenesis) and fat breakdown (lipolysis), potentially leading to a reduction in triglyceride accumulation and improved fat metabolism.

-

Gut Microbiome Modulation: The gut microbiome is increasingly recognized as a significant player in host metabolism, including lipid regulation. A healthy and diverse gut flora can influence bile acid metabolism, short-chain fatty acid production (which can impact liver lipid synthesis), and even the absorption of dietary fats. Cumin, with its fiber content and bioactive compounds, could potentially foster a gut environment conducive to healthier lipid profiles.

-

Impact on Cholesterol Absorption: Some compounds in cumin might interfere with the absorption of dietary cholesterol in the intestines. Plant sterols and stanols, structurally similar to cholesterol, are known to compete for absorption, and while not explicitly identified as high in cumin, its overall matrix of compounds could contribute to this effect.

These hypotheses, while compelling, require rigorous testing in human subjects to determine their clinical relevance. The leap from a plausible biochemical mechanism to a measurable reduction in human cholesterol levels is a significant one.

Chapter 4: The Scientific Scrutiny – Human Studies Reveal the Nuance

The true test of cumin’s cholesterol-lowering potential lies in human clinical trials. While animal and in vitro studies provide valuable mechanistic insights, they don’t always translate directly to human physiology. The research on cumin and cholesterol in humans, while not as extensive as for some other widely studied natural compounds, offers promising, albeit still evolving, insights.

One of the most frequently cited human studies, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial published in 2014 in the Journal of Clinical Lipidology, investigated the effects of cumin powder on lipid profiles in overweight and obese women. Participants were divided into three groups: a control group receiving a placebo, a group receiving 3 grams of cumin powder daily, and another group receiving 75 mg of green coffee bean extract. After eight weeks, the group consuming cumin powder showed significant reductions in total cholesterol, LDL-C, and triglycerides, along with an increase in HDL-C, compared to the placebo group. Specifically, total cholesterol decreased by an average of 15.6 mg/dL, LDL-C by 10.9 mg/dL, and triglycerides by 23.4 mg/dL. HDL-C levels saw a modest but statistically significant increase of 1.9 mg/dL. These findings were quite encouraging, suggesting a tangible positive impact on lipid parameters.

Following this, another study, published in 2017 in the Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine, explored the effects of cumin extract supplementation in patients with mild to moderate hyperlipidemia. In this randomized, placebo-controlled trial involving 60 participants, those receiving 200 mg of cumin extract twice daily for eight weeks demonstrated significant reductions in total cholesterol, LDL-C, and triglycerides, and an increase in HDL-C, compared to the placebo group. The magnitude of change was comparable to the whole powder study, reinforcing the potential benefits. The extract, being more concentrated, might offer a more standardized approach.

A meta-analysis, attempting to synthesize data from multiple randomized controlled trials, provides a broader perspective. While comprehensive meta-analyses specifically focused only on cumin and cholesterol are still emerging, reviews that include various herbs and spices often highlight cumin as having a consistent, albeit modest, positive effect on lipid profiles. These analyses typically conclude that cumin supplementation can lead to small but statistically significant reductions in total cholesterol, LDL-C, and triglycerides, with some studies also showing beneficial effects on HDL-C.

Important Considerations and Limitations of the Research:

Despite these promising findings, it’s crucial for a knowledgeable audience to appreciate the caveats:

- Sample Size and Duration: Many studies on cumin, while well-designed, often involve relatively small numbers of participants (e.g., 60-120 individuals) and are of short duration (e.g., 8-12 weeks). While they demonstrate short-term efficacy, the long-term effects and sustainability of these changes are not yet fully understood.

- Population Specificity: The initial studies often focus on specific populations, such as overweight and obese women, or individuals with mild to moderate hyperlipidemia. Whether these effects translate to other demographics (e.g., men, individuals with severe hyperlipidemia, or those already on cholesterol-lowering medications) requires further investigation.

- Dosage and Form: The effective dose of cumin varies across studies, from 3 grams of whole cumin powder daily to 200 mg of cumin extract twice daily. Standardizing the optimal dose and form (whole seed, ground powder, essential oil, extract) is important for practical recommendations.

- Dietary and Lifestyle Control: While studies attempt to control for confounding variables, the overall diet and lifestyle of participants can still influence results. The impact of cumin might be more pronounced in the context of a healthy diet and regular exercise.

- Mechanism Confirmation: While the studies show an effect on lipid profiles, they don’t always definitively pinpoint the exact mechanisms at play in humans. Further research is needed to correlate observed reductions with specific biochemical pathways.

- Comparison to Pharmaceuticals: The magnitude of cholesterol reduction observed with cumin, while statistically significant, is generally modest compared to the potent effects of pharmaceutical statins. Cumin is more likely to be a complementary strategy rather than a standalone replacement for prescribed medications, especially in cases of severe hypercholesterolemia.

- Heterogeneity of Studies: Differences in study design, participant characteristics, cumin preparation, and outcome measures can make it challenging to directly compare and synthesize findings across all studies.

In essence, the human research on cumin and cholesterol is encouraging, pointing towards a legitimate role for this spice in supporting cardiovascular health. However, it underscores the need for larger, longer, and more diverse trials to solidify these findings and integrate them into clinical practice.

Chapter 5: Animal and In Vitro Studies – Building the Mechanistic Framework

While human trials are the gold standard for clinical efficacy, animal and in vitro (cell culture) studies play a critical role in unraveling the underlying mechanisms and exploring potential benefits that are harder to observe directly in humans. These studies have provided a robust foundation for the hypotheses discussed earlier.

Animal Studies:

Numerous studies in hyperlipidemic animal models (e.g., rats, mice, rabbits fed high-fat diets) have consistently demonstrated cumin’s beneficial effects on lipid profiles.

- Cholesterol and Triglyceride Reduction: In one representative study, rats fed a high-cholesterol diet supplemented with cumin powder showed significantly lower levels of total cholesterol, LDL-C, and triglycerides, and higher HDL-C, compared to the control group receiving only the high-cholesterol diet. These effects were often comparable to or even synergistic with standard cholesterol-lowering drugs in some models.

- Liver Protection: Animal studies have shown that cumin can mitigate diet-induced fatty liver disease, a condition often associated with hyperlipidemia. It appears to reduce hepatic lipid accumulation and improve liver enzyme markers, suggesting a protective role for the liver, the primary organ for lipid metabolism.

- Antioxidant and Anti-inflammatory Effects in Vivo: In animal models, cumin administration has been shown to increase antioxidant enzyme activity (e.g., superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione peroxidase) and reduce markers of oxidative stress (e.g., malondialdehyde levels) in tissues, including the liver and heart. It has also reduced inflammatory markers, corroborating its anti-inflammatory potential in a living system.

- Gene Expression Modulation: Some animal studies have delved into the molecular level, observing that cumin supplementation can alter the expression of genes involved in cholesterol synthesis, transport, and catabolism. For example, it might downregulate genes involved in HMG-CoA reductase activity and upregulate genes involved in bile acid synthesis and excretion.

In Vitro Studies (Cell Culture and Biochemical Assays):

Studies conducted in test tubes and cell cultures allow researchers to isolate specific interactions and mechanisms without the complexities of a whole organism.

- HMG-CoA Reductase Inhibition: Cell-free assays and liver cell cultures have demonstrated that specific compounds isolated from cumin can directly inhibit the activity of HMG-CoA reductase, supporting the hypothesis that cumin might act as a natural "statin-like" compound, albeit with lower potency.

- Antioxidant Capacity: In vitro assays confirm cumin’s high antioxidant capacity through various mechanisms, including free radical scavenging and metal chelation. This reinforces its potential to protect LDL from oxidation.

- Anti-inflammatory Signaling: Cumin extracts have been shown to modulate inflammatory pathways in cell cultures, such as inhibiting the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-alpha, IL-6) and reducing the activation of NF-κB, a key transcription factor involved in inflammatory responses.

- Adipocyte Differentiation: Some studies have explored cumin’s effects on adipocytes (fat cells), suggesting it might influence their differentiation and lipid accumulation, further linking it to overall lipid metabolism.

These preclinical studies provide a compelling mechanistic narrative, outlining how cumin, through its complex array of bioactive compounds, could exert its beneficial effects on cholesterol and overall cardiovascular health. They strengthen the rationale for human trials and help guide future research directions. However, it’s a crucial scientific principle that observations in a petri dish or a rodent do not automatically equate to human clinical efficacy. They merely point the way.

Chapter 6: Beyond Cholesterol – Other Potential Health Benefits of Cumin

While our primary focus is on cholesterol, it would be remiss to overlook the broader spectrum of health benefits attributed to cumin. These additional properties further enhance its profile as a valuable dietary inclusion, potentially offering synergistic effects that contribute to overall metabolic health, which is intricately linked to cardiovascular well-being.

-

Weight Management: Several human studies have investigated cumin’s role in weight loss. The same 2014 study that showed cholesterol reduction in overweight women also reported significant reductions in body weight, BMI, and waist circumference in the cumin group compared to the placebo. Other research suggests that cumin, particularly in the form of a supplement, might aid in reducing body fat mass. The mechanisms could include improved lipid metabolism, enhanced thermogenesis, and potential appetite modulation.

-

Blood Sugar Control: Emerging research suggests cumin may have a role in managing blood glucose levels, particularly relevant for individuals with prediabetes or type 2 diabetes. Animal studies and some human trials have shown that cumin can reduce fasting blood glucose, HbA1c (a marker of long-term blood sugar control), and improve insulin sensitivity. This effect is likely due to its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, as well as its potential to influence enzymes involved in glucose metabolism.

-

Digestive Health: This is perhaps cumin’s most ancient and well-established traditional use. Its carminative properties help relieve gas and bloating. The volatile oils in cumin can stimulate the secretion of digestive enzymes, improving overall digestion. It has also shown promise in alleviating symptoms of Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS), likely due to its antispasmodic and anti-inflammatory effects on the gut.

-

Anti-Cancer Potential: Preliminary in vitro and animal studies have explored cumin’s anti-cancer properties. Compounds like cuminaldehyde have demonstrated the ability to inhibit the proliferation of various cancer cell lines and induce apoptosis (programmed cell death). While this research is still in its very early stages, it highlights another intriguing avenue for cumin’s therapeutic potential.

-

Antimicrobial Activity: Cumin essential oil has shown broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity against certain bacteria and fungi, including some drug-resistant strains. This traditional application is now gaining scientific backing, suggesting its potential as a natural preservative and even a topical agent.

-

Cognitive Enhancement: Some animal studies have indicated that cumin might have neuroprotective effects and improve memory, possibly due to its antioxidant capacity protecting brain cells from oxidative damage.

These additional benefits paint a picture of cumin as a multifaceted spice, offering more than just cholesterol modulation. Its contribution to overall metabolic health, weight management, and blood sugar control can indirectly support cardiovascular health, making it a valuable dietary component.

Chapter 7: Practical Considerations and Integrating Cumin into a Health Strategy

Given the promising research, how can a knowledgeable individual practically consider incorporating cumin into their health regimen, particularly for cholesterol management?

-

Forms of Cumin:

- Whole Seeds: Can be toasted and ground, or added directly to dishes. They retain the fiber and oil content.

- Ground Powder: Convenient for cooking and adding to drinks. Ensure it’s fresh for maximum potency.

- Cumin Extract/Supplements: These offer a more concentrated and standardized dose, which might be preferable for targeted therapeutic effects. However, quality varies, so choose reputable brands.

- Cumin Essential Oil: Highly concentrated and should be used with extreme caution, often diluted, and preferably under professional guidance. Not typically recommended for internal consumption for cholesterol management.

-

Dosage: Based on the human studies, a daily intake of 3 grams of cumin powder or 200-400 mg of cumin extract appears to be a common and effective range. This could translate to roughly half a teaspoon to a full teaspoon of ground cumin powder daily.

-

Culinary Integration:

- In Cooking: Cumin is incredibly versatile. Add it to curries, stews, soups, lentil dishes (dal), chili, tacos, roasted vegetables, and rice.

- Cumin Water/Tea: A simple and traditional way to consume cumin is to soak a teaspoon of whole seeds overnight in water, then boil and strain the water in the morning, drinking it on an empty stomach. Or brew a tea with ground cumin.

- Yogurt/Smoothies: A pinch of ground cumin can be added to yogurt or savory smoothies.

-

Safety and Side Effects: Cumin is generally recognized as safe (GRAS) when consumed in culinary amounts. In the therapeutic doses used in studies, it has been well-tolerated with few reported side effects.

- Gastrointestinal: Some individuals might experience mild digestive upset, gas, or heartburn, especially with higher doses.

- Blood Sugar: As cumin may lower blood sugar, individuals with diabetes on medication should monitor their glucose levels closely to avoid hypoglycemia.

- Blood Thinners: Cumin has mild anticoagulant properties, so those on blood-thinning medications (e.g., warfarin) should exercise caution and consult their doctor due to a potential increased risk of bleeding.

- Allergies: Although rare, allergic reactions to cumin can occur.

- Pregnancy and Lactation: While traditionally used, therapeutic doses of cumin should be discussed with a healthcare provider during pregnancy and lactation due to limited research on safety in these populations.

-

Holistic Approach and Medical Supervision: It is absolutely crucial to emphasize that cumin, or any natural remedy, should not be viewed as a standalone cure for high cholesterol or a replacement for prescribed medications.

- Lifestyle is Paramount: Dietary changes (reducing saturated and trans fats, increasing fiber, eating whole foods), regular exercise, maintaining a healthy weight, and stress management remain the cornerstones of cholesterol management.

- Consult Your Doctor: Individuals with high cholesterol, especially those with pre-existing cardiovascular conditions or those on medication, must consult their healthcare provider before significantly increasing their cumin intake or starting any new supplement. Cumin can be a valuable adjunct to a comprehensive health plan, but professional medical guidance is indispensable. Your doctor can help integrate it safely into your treatment plan and monitor its effects.

Chapter 8: The Road Ahead – What Future Research Must Reveal

Our journey through the research on cumin and cholesterol reveals a compelling narrative of potential, yet also highlights the scientific path still to be traversed. For cumin to move from a promising traditional remedy to a widely recommended clinical intervention for hyperlipidemia, future research must address several key areas:

- Larger, Long-Term, Multi-Center Trials: The most pressing need is for robust, large-scale, randomized, placebo-controlled trials conducted over longer durations (e.g., 6 months to several years) across diverse populations. These studies would provide stronger evidence for sustained efficacy, assess long-term safety, and identify optimal dosing strategies.

- Comparative Effectiveness Studies: Research comparing the efficacy of cumin (in various forms and doses) against established cholesterol-lowering agents (like statins) or other natural alternatives would provide valuable context for its place in a therapeutic hierarchy.

- Mechanism Elucidation in Humans: While preclinical studies offer mechanistic hypotheses, confirming these mechanisms in human subjects (e.g., through biomarker analysis, gene expression studies in target tissues, or advanced imaging techniques) would solidify our understanding of how cumin exerts its effects.

- Standardization of Cumin Extracts: The composition of cumin can vary based on growing conditions, processing, and storage. Developing standardized extracts with known concentrations of bioactive compounds would ensure consistency and reproducibility of effects across studies and in commercial products.

- Drug-Nutrient Interactions: More detailed research into potential interactions between cumin (especially in concentrated forms) and common cardiovascular medications (e.g., statins, anti-platelet drugs) is essential to ensure patient safety.

- Targeted Populations: Further studies could focus on specific patient groups, such as those with metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, or individuals who are statin-intolerant, to explore if cumin offers particular benefits in these niches.

- Impact on Hard Endpoints: Ultimately, the most important question is whether cumin can not only lower cholesterol levels but also reduce the incidence of cardiovascular events (heart attacks, strokes) and mortality. This requires very large, long-term outcome studies, which are costly and complex but represent the highest level of evidence.

The scientific narrative around cumin and cholesterol is still being written. Each study, each meta-analysis, adds another paragraph, another chapter to this unfolding story. The current evidence is promising, suggesting that this humble seed holds genuine potential. But the rigorous pursuit of knowledge demands continued investigation, ensuring that any recommendations are built on an unshakeable foundation of evidence.

Conclusion: A Spice of Promise, a Journey of Discovery

Our exploration into the question, "Can cumin lower your cholesterol?" reveals a nuanced and evolving answer. The research, spanning ancient wisdom, modern biochemistry, animal models, and a growing body of human clinical trials, points towards a compelling conclusion: Yes, cumin can indeed contribute to improved lipid profiles, offering a modest but statistically significant reduction in total cholesterol, LDL-C, and triglycerides, while potentially increasing beneficial HDL-C.

This is not a pronouncement of a miracle cure, nor an assertion that cumin replaces the efficacy of pharmaceutical interventions for severe hypercholesterolemia. Rather, it is an acknowledgment of a natural compound with genuine therapeutic potential, one that aligns with humanity’s age-old quest for holistic well-being. Cumin, rich in antioxidants, anti-inflammatory compounds, and dietary fiber, appears to act through multiple pathways to positively influence lipid metabolism.

For the knowledgeable audience, the story of cumin and cholesterol is one of cautious optimism. It underscores the profound interconnectedness of diet and health, reminding us that even the smallest seeds hold immense power. As we navigate the complexities of modern health challenges, the inclusion of such potent, natural allies in our diet, especially as part of a comprehensive lifestyle strategy, offers a promising path forward.

The journey of discovery is ongoing. While the research revealed thus far paints an encouraging picture, the scientific community continues its meticulous work, striving to unravel every facet of cumin’s potential. Until then, we can embrace this ancient spice, not just for its ability to tantalize our taste buds, but for its quiet, yet profound, contribution to our cardiovascular health, adding another flavorful chapter to the grand narrative of natural medicine. The spice rack, it seems, still holds many secrets waiting to be fully understood and appreciated.